($VIRT) Virtu Financial: There's a global shortage of liquidity and Virtu is selling

A beneficiary of indexation and a perpetual call option on volatility (that pays you for holding in the meantime)

********** UPDATE 20241217: Interesting development as activist shareholders are now pushing for sale of the company, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/activist-investor-pulte-calls-for-virtu-financial-to-be-sold-302334188.html **********

********** UPDATE 20231004:

Seeing things open market buys like from CEO Cifu is encouraging when the stock is down nearly 30% since the time I bought most of my shares:

*********

********** UPDATE 20221110: This post is only partially completed (and it’s obvious near the end of the post), but I keep it up just for my own reference on certain sections that I still think are useful and I do still own the stock **********

Yet, liquidity is merely a synonym for trading activity. Thus, one would say a given security trades at great volume because it is liquid and it is liquid because it trades at great volume. —- Murray Stahl, “Further Basic Principles of Croupier Investing”

Overview

Valuation seems reasonable on a multiples basis

High insider ownership (though mgmt’s ownership structure is opaque)

Long-volatility allocation

Market makers profit from retail trader order flow ==> long retail degeneracy (or hedge against your own degeneracy)

Betting on continued longterm trend of increasing indexation and subsequent volatility, liquidity supply deficits, and widening bid/ask spreads in markets

The indexation trend steadily continues and now makes up more than 50% of US equity flows

Indexation reduces supply of market liquidity ⇒ wider spreads ⇒ $ for market makers like VIRT

Indexation increases market volatility ⇒ wider spreads ⇒ $ for market makers like VIRT

+ Longer term trend of asset digitization (eg. the financialization of nature via carbon allowance futures etc) ⇒ more trading volumes ⇒ $ for VIRT

VIRT’s ability to hedge a portfolio’s actual market value against volatility provides convexity (ie. there are many vol beneficiaries, but the ones whose actual price correlation with the general market does not rise with volatility are the ones that are going to be a positive influence on your psychology in those mentally distressing times (and so have the added benefit of mitigating urges to do something stupid at the worst of times))

A 66%Benchmark/33%Volatility portfolio (using VIRT and ABRTX for vol) maintains a significantly higher Sortino ratio and less severe drawdowns than the 100%Benchmark portfolio, while maintaining a similar CAGR in backtest starting from VIRT’s IPO

Bond-like characteristics without the same interest rate duration risk

Table of Contents

First blush

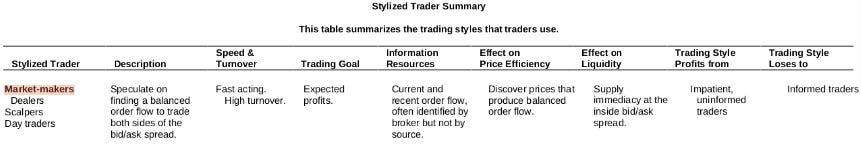

“Market-makers provide liquidity to impatient traders. They try to turn their inventory at a profit. To profit, they must trade at prices that produce a balanced order flow on both sides of the bid/ask spread. [...] Market-makers provide immediacy by connecting liquidity demands through time.”, The Winners and Losers of the Zero-Sum Game: The Origins of Trading Profits, Price Efficiency and Market Liquidity by Lawrence Harris

After reading the article here on the benefits of building convexity into an investment portfolio, I’ve been looking for ideas on how to implement this strategy with volatility beneficiaries – without the steep negative carry of the roll yields that comes with simply buying VIX short term ETNs and without having to trade options (I’m looking for things that would have a positive or at least net-zero return that can be held for the long run) – by the way, just as a little spice, the US government is currently only funded until Feb 18 2022 (just a few week away from this writing).

To this end, I think that Virtu Financial is an interesting idea1 that also benefits from tailwinds from indexation, volatility (as market valuations and breadth become stretched and investors become of more nervous and fickle in our current market environment), the democratization of investing — and thus trading volumes — via platforms like Robinhood promoted by social media like TikTok, Reddit, et al (how do you think I ended up writing this blog?), and on the impending wealth transfer from boomers to millennials and gen z’ers — that has potentially been pulled forward by deaths during the 2020 pandemic. VIRT profited from vol in 2020, and 2021, and as I’m writing this the lineup for 2022 – with inflation, midterms, a looming fiscal cliff, continued supply chain issues, talks of drastic rate hikes, and potential for some version of war with Russia – looks likely to be more conducive to volatility not less.

For a general reference, the VIC article here is a good rundown — my interest in VIRT is mainly from the POV of how market-makers work, how VIRT benefits from continued market indexation, and the case for a VIRT allocation in service of portfolio convexity.

In any case, VIRT continues to control 25% of the market maker business, act as simple portfolio insurance (or portfolio convexity) for the long run without the roll decay of a typical VIX ETP nor K-1 forms come tax season, and pay a 3% dividend with a shareholder aligned owner-operator, currently trading at a 7x P/E with earnings that I think indexation trends are going to sustain if not elevate.

Biggest risks appear to be what congressional action against PFOF would look like and how that would affect the business – or a KCG-esque blowup.

Note that I don’t think that options dealers and market makers like VIRT are good hedges against a prolonged depression (as volumes would likely dry out Great Depression style), but rather that stocks like CME, CBOE, and VIRT are “volatility beneficiaries” and – given the importance of convexity in a portfolio and the underappreciation of volatility as an asset class – that makes them unique considerations from a portfolio-level POV.

Benefiting from indexation, liquidity deficits, and vol

“The problem with conventional indexation is that, ultimately, every index will eventually undiversify. This is simply the arithmetical consequence of the fact that the best index investments, in terms of performance, must ultimately become the biggest investments. Moreover, since the sum of the parts must equal the whole, other index investments that at index inception were diversifying assets, are necessarily minimized in weighting. For example, the energy weighting of the S&P 500 index has never been so small; it is now only 2.56%. This could be a problem if there were a meaningful increase in energy prices.”, Murray Stahl (2020 shareholder letter)

“The extraordinary growth of short volatility strategies creates risks that may trigger the next serious market crash. A low yield, low volatility environment has drawn various market participants into essentially similar short volatility contingent strategies with a common non-linear risk factor. […] The risk is greater than most would think because most traders are unaware of the extent to which their trading strategies are correlated with those of others who engage in seemingly different strategies. […] Market participants and regulators can both benefit from being prepared for large, self-reinforcing technical unwinds that may occur when events cause these traders to reevaluate their risk tolerance.”, Everybody’s Doing It: Short Volatility Strategies and Shadow Financial Insurers (2018)

“That’s what we’ve learned from 50 or 60 years of operating businesses that if you can find a great business that doesn’t require capital, when it grows, you’ve really got something.“, Warren Buffett 2020 shareholder meeting

Widening bid/ask spreads = more revenue for market makers

Deterioration of market liquidity = more vol = wider spreads = more revenue captured by market makers

Indexation ==> shortage of “supply” / biodiversity of differing investment opinions (or at least their expressions in the market) ==> shortage of liquidity (b/c everyone in the market is expressing the same opinion (everyone is in the indexes and they all buy and sell the same things at same time)) ==> increased volatility and wider bid/ask spreads, both of which benefit revenues of VIRT’s capex-light, 65% profit margin, market making business business w/out the need for any significant additional investment (maybe they’ll need to add another server or two). ==> Indexation == Structural tailwind for VIRT and other market makers (basically any business that makes money primarily by hosting trading volumes)

Indexation is growing and have been making up a larger and larger share of the market over time.

Indexation reduces market liquidity…

“The increase in index investing, academics have found, has led to an increase in trading costs, or more specifically, a widening in bid-ask spreads and a deterioration in market liquidity. […] This problem can only get worse, as more and more assets flow into index funds and as market liquidity deteriorates and bid-offer spreads widen further.“, Is there a dark side to exchange-traded funds? Israeli, D. Lee, C., Sridharan, S, 2016

… which DMMs supply

“Market-makers provide liquidity to impatient traders. They try to turn their inventory at a profit. To profit, they must trade at prices that produce a balanced order flow on both sides of the bid/ask spread. [...] Market-makers provide immediacy by connecting liquidity demands through time.”, The Winners and Losers of the Zero-Sum Game: The Origins of Trading Profits, Price Efficiency and Market Liquidity by Lawrence Harris

https://intelligencequarterly.com/markets/greetings-from-our-macro-friend/

(The ultimate significance of depth of market for viewing liquidity is debated here)

An SEC investigation in 2015 concluded that passive investing products cause an increase in market volatility…

“Additional time-series evidence suggests that ETFs introduce new noise into the market, as opposed to just reshuffling existing noise across securities. […] We present results showing that the stocks in ETFs’ baskets display higher volatility than otherwise similar securities. Through a regression discontinuity design, we are able to attach a causal interpretation to this finding. The presence of ETFs also causes the underlying securities’ prices to diverge from random walks, both intraday and daily. These effects are significantly related to proxies for the intensity of arbitrage activity between the ETFs and their baskets. This evidence paints a picture in which noise trading in the ETF market is passed down to the prices of the underlying securities by the transmission chain of arbitrage trades. Moreover, because of their ease of trade and cost effectiveness, ETFs attract higher turnover investors than the average stock in their baskets. Consequently, noise in stock prices increases with ETF ownership.”, Do ETFs Increase Volatility? (2015)

… which widens bid/ask spreads.

Here is a 10 year 12-month rolling correlations between some of the major category ETFs vs the S&P 500

Notice that all of the major category ETFs (ex. EEM) are nearly 90-100% correlated to the index (including both value and growth ETFs, interestingly)

More talk of the effects and trends of indexation and passive investing here, here, here, here, and here.

Here’s Micheal Burry hating on indexation: https://www.fa-mag.com/news/-big-short--hero-explains-why-index-funds-are-like-subprime-cdos-51461.html

“Central banks and Basel III have more or less removed price discovery from the credit markets, meaning risk does not have an accurate pricing mechanism in interest rates anymore. And now passive investing has removed price discovery from the equity markets. The simple theses and the models that get people into sectors, factors, indexes, or ETFs and mutual funds mimicking those strategies -- these do not require the security-level analysis that is required for true price discovery.”

“This is very much like the bubble in synthetic asset-backed CDOs before the Great Financial Crisis in that price-setting in that market was not done by fundamental security-level analysis, but by massive capital flows based on Nobel-approved models of risk that proved to be untrue.”

“In the Russell 2000 Index, for instance, the vast majority of stocks are lower volume, lower value-traded stocks. Today I counted 1,049 stocks that traded less than $5 million in value during the day. That is over half, and almost half of those -- 456 stocks -- traded less than $1 million during the day. Yet through indexation and passive investing, hundreds of billions are linked to stocks like this. The S&P 500 is no different -- the index contains the world’s largest stocks, but still, 266 stocks -- over half -- traded under $150 million today. That sounds like a lot, but trillions of dollars in assets globally are indexed to these stocks. The theater keeps getting more crowded, but the exit door is the same as it always was. All this gets worse as you get into even less liquid equity and bond markets globally.”

And in every one of these market tumults, VIRT and other DMMs are the ones selling the fast-passes at the exit door because, again, …

“Market-makers provide liquidity to impatient traders. They try to turn their inventory at a profit. To profit, they must trade at prices that produce a balanced order flow on both sides of the bid/ask spread. [...] Market-makers provide immediacy by connecting liquidity demands through time.”, The Winners and Losers of the Zero-Sum Game: The Origins of Trading Profits, Price Efficiency and Market Liquidity by Lawrence Harris

So again, indexation increases crowded investments, which results in greater volatility swings, which results in wider spreads that market makers can charge for the risk they take on for providing liquidity every time these ever-larger crowds rush for the exits.

More about this here: https://www.reuters.com/business/us-stock-market-liquidity-abysmal-adding-volatility-risk-2022-02-07/

As I write this, the bond markets are expecting a 50bps rate hike with the possibility of further pain that would likely add vol into the markets — with VIRT set to benefit.

Value of portfolio convexity

See https://convex-strategies.com/2021/10/19/risk-update-september-2021/

VIRT’s ability to hedge a portfolio’s actual market value against volatility (particularly on the left tail) provides portfolio convexity (ie. there are many vol beneficiaries, but the ones whose actual price correlation with the general market does not rise with volatility are the ones that are going to be a positive influence on your psychology in those mentally distressing times (and so have the added benefit of mitigating urges to do something stupid at the worst time)).

From Howard Mark’s memo on “Selling Out“:

Switching gears, what about the idea of selling because you think a temporary dip lies ahead that will affect one of your holdings or the whole market? There are real problems with this approach:

• Why sell something you think has a positive long-term future to prepare for a dip you expect to be temporary?

• Doing so introduces one more way to be wrong (of which there are so many), since the decline might not occur.

• Charlie Munger, vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, points out that selling for market-timing purposes actually gives an investor two ways to be wrong: the decline may or may not occur, and if it does, you’ll have to figure out when the time is right to go back in.

• Or maybe it’s three ways, because once you sell, you also have to decide what to do with the proceeds while you wait until the dip occurs and the time comes to get back in.

• People who avoid declines by selling too often may revel in their brilliance and fail to reinstate their positions at the resulting lows. Thus, even sellers who were right can fail to accomplish anything of lasting value.

• Lastly, what if you’re wrong and there is no dip? In that case, you’ll miss out on the ensuing gains and either never get back in or do so at higher prices

Here we can backtest a portfolio of 33%SPY/33%QQQ/33%volatility (via VIRT and ABTRX positions) vs portfolios without volatility exposure from 2016 to present:

We see the vol-hedged portfolio comes out with a significantly higher Sortino ratio, while maintaining similar CAGR as well as a much milder max drawdown relative to the index. Note that many investors fail to even achieve those benchmark results due to getting scared out of the market on those high-vol days that the vol-allocation portfolio helps buffer you from.

From Howard Marks’ “Selling Out“ section on retail and professional investors:

For example, studies have shown that the average mutual fund investor performs worse than the average mutual fund. How can that be? If she merely held her positions, or if her errors were unsystematic, the average fund investor would, by definition, fare the same as the average fund. For the studies’ findings to occur, investors have to on balance reduce the amount of capital they have in funds that subsequently do better and increase their allocation to funds that go on to do worse. Let me put that another way: on average, mutual fund investors tend to sell the funds with the worst recent performance (missing out on their potential recoveries) in order to chase the funds that have done the best (and thus likely participate in their return to earth).

However, when including a significant vol allocation, you 1) have a bit of a psychological cushion to prevent panic selling during left-tail downturn events and 2) actually end up raising cash — as opposed to selling out of existing positions at lows — that can be reallocated into those distressed assets as you rebalance.

VIRT’s business

Virtu IPO’ed only a year ago from this point as one of the first pure-play HFT market maker stocks – with KCG being the main comp (which was acquired by Virtu in 2017). The main uncertainties at the time appeared to be the generally poor public – and subsequently congressional – sentiment towards HFTs (eg. one of Virtu’s subsidiaries got in trouble in France for “market manipulation” (reading the description does not actually seem like Virtu manipulated anything in the conventional sense)). In any case, geopolitical concerns and a market wary of changes in interest rates boosts the prospects for the vol and volumes that Virtu benefits from as a market maker (note that both of these elements are things that Virtu cannot directly influence which may be concerning to investors).

The complex share ownership structure is another point of concern for investors worried about a firm run by financial engineers profiting at the expense of common class A shareholders as well as the potential for a fatal blowup as had already been seen at HFTs Knight Capital and FXCM (as a bit of an aside, I believe that Virtu was more diversified than these firms both geographically and by asset classes at this time).

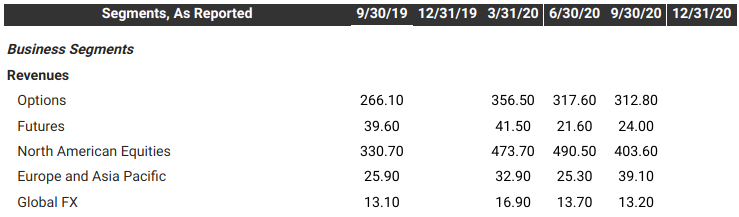

VIRT’s main business is market making (80% of 2020 revenue), followed by execution services (20%)

https://www.fi-desk.com/market-structure-meet-the-new-market-makers/

Market making

The company has over 30% market share for retail investor order flow -- and it pays a lot of money for the privilege. Market makers pay brokers to route their clients' orders to them, so the market maker can earn a profit on the bid/ask spread -- the difference between the buy and sell price -- when executing the trade., https://www.fool.com/investing/2021/05/20/why-you-need-to-know-about-virtu-financial/

Virtu's market making business makes up ~77% of their revenues. My basic understanding of the market making business is this (note, some of these acronyms are just my own shorthand for understanding)2:

Think of any retail broker (eg. Charles Schwab) or wealth management firm (eg. UBS), collectively broker-dealers (BDs). These businesses all aggregate order flow from their clients. When a trading order is placed, that order is sent to either one of 15 national securities exchanges (I’ll call NSEs), 40 alternative trading systems (ATS, or “dark pools”3), or a pool of designated market makers (DMMs). When orders are sent to an NSE they have the visibility of the national best bid and offer (NBBO) printed by the NSEs and DMMs (note that the bid and ask prices can come from different NSEs and DMMs).

When order flow is sent to the NSEs, the BDs must pay a consolidated market data feed fee as well as transaction fees to the exchange. On the other hand, when BDs send order flow to the DMMs, they get rebates given back to them rather than having to pay for the execution. My understanding is that BDs send percentages of their order flow to different DMMs based on their price improvement on NBBO – which gets reviewed on a periodic basis determined by the Best Execution Committees at the individual BDs (by periodic, this can be weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc). So if Citadel has the best price improvement on NBBO for a given period, they get 40% of the order flow, if Virtu is second best they get 20%, and so on. You can usually see your broker’s price improvement statistics by googling “<your BD here> price improvement statistics”. You can also see your BD’s routing flow by googling “<your BD here> SEC Form 606 disclosures”.

(There are also ATSs that orders can be executed on. My understanding is that in the early days of the stock exchange, ATSs were set up by institutional players to avoid manipulation and other abuses that were happening on the NSEs. These exchanges – which did not print their order price and depth data – were allowed by the SEC provided that they did not control more that 5% of daily market volume. With this, larger orders could be placed while mitigating market price impact that would otherwise show up in the level 2 data feeds available from NSEs).

https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/slicing-the-liquidity-pie-2019-02-11

Suppose you send a limit order to buy 10 shares of stock XYZ at $7.50 (let’s suppose the NBBO is bid=$7.45x5 and ask=8.50x15). Your BD has several options of where to send this order. If the BDs were to just send that order straight to a NSE, you would fill 5 of those shares (maybe not even at the NBBO bid if your order instead gets matched with a $7.50 limit sell order of the same volume), but would then likely need to move up in price since you’ve now taken out all of the shares available at that previous bid price level.

If instead, your BD routed the order to a DMM, that DMM guarantees to execute your trade at NBBO or better at the time the order was placed. The DMM has the technology to merge together all of the NSE and ATS markets and find the XYZ shares trading at NBBO or better. They will scan the markets and buy the 5 shares of XYZ from the NSE for $7.45 as well as find any shares of XYZ trading in ATS markets for NBBO or better to fill the order. Suppose they find 5 more shares of XYZ for that same NBBO bid price of $7.45 in a dark pool ATS. They took your $7.50x10 buy order and bought XYZ $7.45x10, capturing a spread of 5c/share = 50c. From this spread, the DMM takes a % – say 10c – and the remaining 40c is given back to the BD as price improvement, so you see that you were able to buy the 10 shares for $7.46/share.

However, the DMM also gives back a rebate to the BD for the privilege of receiving the BD’s order flow – my understanding is that this is based on a fixed cost set by the individual BD (in this example, say 0.25c) per 100 trades – this is payment for order flow (PFOF). This payment is due to the fact that the DMM is making money on the order flow and the BD recognizes the value of this to the DMM and thus wants to be compensated as well – I guess providing an extra feature of price improvement to clients is not value enough for the BD.

What makes retail order flow, like mine, valuable is the fact that individual retail trades tend to be less correlated (read as: less informed) to overall market movements and thus DMMs are less likely to get killed being on the opposite end of a limit up/down situation —like they did during the GameStop situation in late 2020 when DMMs had to maintain two sides of the market to “make” it but were hit with orders only in one direction. From “The Winners and Losers of the Zero-Sum Game: The Origins of Trading Profits, Price Efficiency and Market Liquidity” by Lawrence Harris:

Market-makers provide liquidity to impatient traders. They try to turn their inventory [in this case the large portfolio of managed securities that the DMM buys, in this example, and sells in the case of liquidity enhancement] at a profit. To profit, they must trade at prices that produce a balanced order flow on both sides of the bid/ask spread. They find these prices by experimentation. Their inventory turnover may be extremely high.

Market-makers lose to informed traders. Market-makers must carefully analyze order flow to identify informed traders. The task is difficult because orders typically are identified only by broker and not by beneficial trader. Market-makers widen their spreads to recover from uninformed traders what they lose to informed traders. This widening of the bid/ask spread is called the adverse selection spread component. Market-makers profit from impatient uninformed traders.

Successful market-makers must pay attention continuously. They must integrate information about the order flow, they must keep track of their own positions, and they must make good decisions quickly.

Market-makers supply liquidity in the form of immediacy at the inside bid/ask spread. Because they fear trading with informed traders who they cannot identify, they are reluctant to offer liquidity to large traders.

Market-makers make prices more efficient through their efforts to find prices that produce balanced order flow. One-sided order flows often indicate [I’m sure some would disagree in the case of $GME] that value-motivated traders or informed traders think securities are misvalued.

From this POV, VIRT would also be thought of as a bet on continued retail degeneracy or a hedge against your/my own trading degeneracy —personally, making this an even more attractive holding for my own account (and honestly I don’t think HFs and other big institutional money is really that much better, either).

BTW, while the article I link to for the GME 0.00%↑ situation characterizes the event as a short squeeze, the SEC’s report on the GME event would disagree and —rather then chalk it up to internet degeneracy— took a stance more in the direction of it being a product of legitimate price discovery (or as Harris might say ‘value-motivated traders or informed traders thinking securities are misvalued’):

Underneath the memes are actual companies, with employees, customers, and plans to invest in the future. Those who bought GameStop became co-owners of a company through a system of mutual trust and participation that sustains our economy. People may disagree about the prospects of GameStop and the other meme stocks, but those disagreements are what should lead to price discovery rather than disruptions.

IDK what to make of that, I just thought is was interesting.

2021 10K notes:

We make markets in a number of different asset classes, which are discussed in more detail below. We register as market makers and liquidity providers where available and support affirmative market making obligations.

We provide competitive and deep liquidity that helps to create more efficient markets around the world. We stand ready, at any time, to buy or sell a broad range of securities, and we generate revenue by buying and selling large volumes of securities and other financial instruments while earning small bid/ask spreads.

We believe the overall level of volumes and realized volatility in the various markets we serve have the greatest impact on our businesses. Increases in market volatility can cause bid/ask spreads to temporarily widen as market participants are more willing to transact immediately and as a result market makers’ capture rate per notional amount transacted increases.

BTW, this is how the S&P realized volatility indexes are calculated45:

Basically, if the day-over-day price changes on the underlying index that RV is measuring are always highly spread apart from a static 0% – or are rising to become highly dispersed from the assumed zero-mean – over an N-day lookback window, then RV is going to be high. Another way to think of this is that RV is high when the acceleration in day-over-day price changes are high, regardless of direction up or down. This tends to happen during periods of high uncertainty. To illustrate this, I’ve added the drawing below (where one series is clearly more uncertain about where it wants to be than the other):

Since we are using a zero-mean, the RV is proportional to the sum of the distances of the sequential points in the series – that is, the sum of the lengths of the connecting lines. Clearly, by this measure, the volatility of the lower series is much greater than that of the upper.

Horizon Kinetics’ Murray Stahl also had some interesting commentary on the VIX, what it really means/represents, and market moods in “The VIX: A Mathematical Abstraction” segment of a 2010 Q&A published here.

Further reading:

Execution Services

The execution services segment makes up 23% of Virtu’s revenue and provides infrastructure for clients to execute trades piggybacking on Virtu's HFT technology. This includes algorithms, routing services to various light and dark pools, dark pool allocation services, and routing between Canadian and US exchanges depending on advantageous/optimal FX exchange rates. Virtu offers the ability to track these processes in real time and provide reports on executed orders6.

2021 10K notes:

We offer client execution services and trading venues that provide transparent trading in global equities, ETFs, fixed income, currencies, and commodities to institutions, banks and broker-dealers. We generally earn commissions when transacting as an agent for our clients. Client-based, execution-only trading within this segment is done through a variety of access points including: (a) algorithmic trading and order routing; (b) institutional sales traders who offer portfolio trading and single stock sales trading which provides execution expertise for program, block and riskless principal trades in global equities and ETFs; and (c) matching of client conditional orders in POSIT Alert and in our ATSs, including Virtu MatchIt and POSIT. We also earn revenues (a) by providing our proprietary technology and infrastructure to select third parties for a service fee, (b) through workflow technology and our integrated, broker-neutral trading tools delivered across the globe, including order and execution management systems and order management software applications and network connectivity and (c) through trading analytics, including (1) tools enabling portfolio managers and traders to improve pre-trade, real-time and post-trade execution performance, (2) portfolio construction and optimization decisions and (3) securities valuation.

We offer agency execution services and trading venues that provide transparent trading in global equities, ETFs, fixed income, currencies, and commodities to institutions, banks and broker dealers. We generally earn commissions when transacting as an agent for our clients.

Management

Vincent Viola (Chairman Emeritus)

Ex chairman of the New York Mercantile Exchange and Virtu founder Vincent Viola owns 38% of Virtu Financial class A shares through paired class D stock and takes no director compensation as Virtu’s Chairman Emeritus, so is well aligned with shareholders. Note that Viola retains 80% of voting power at the company via class B shares.

Robert Greifeld (Chairman)

Former CEO of the NASDAQ, Robert Grefield is the current Chairman of Virtu and owns 11% of Virtu Financial through North Island Ventures LLC, which was jointly owned with Glenn Hutchins (collectively the “NIH Reporting Persons” in the DEF14A, see “Agreements Entered into in Connection with the Acquisition of KCG Holdings, Inc.”) — but Hutchins has since resigned.

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/0001592386/000110465921054475/tm2113222-1_def14a.htm#tSOOC

Greifeld joined in 2017 as part of Virtu’s acquisition of rival market maker KCG holdings. My understanding is that Grefield (and Hutchins) are executives at PE firm North Island Ventures and helped fund the KCG acquisition and received their Chairman and director positions as part of that deal.

Douglas Cifu (CEO)

CEO Douglas Cifu owns 4.4MM shares (when including direct and indirect ownership) amounting to a total value of $132MM (using a price of $30/share, 20220110) which represents 11-33x multiples of Cifu’s total annual compensation.

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/0001592386/000110465921054475/tm2113222-1_def14a.htm#tEXCO

Financial strength

Some quick balance sheet health metrics

https://www.gurufocus.com/term/rank_balancesheet/NAS:VIRT/Financial-Strength/Virtu-Financial

Other market makers

While VIRT is the only public pure play DMM, there are other publicly traded businesses that have market making businesses. Here we can see these market makers (+ some other vol beneficiaries CBOE and CME) rolling 12 month correlations to the S&P 500

Notice that VIRT’s stock price is the only one to move in any kind of positive correlation with the VIX (not even CBOE who owns the VIX index shows that kind of behavior) as well as showing the lowest correlation with the broader market aside from the VIX.

Here, we can look at a quick chart showing how they reacted during the 2020 COVID crash relative to the VIXM midterm futures

VIRT vs other vol beneficiaries?

Looking at the chart below, which best sustains a correlation with the VIX index? (The direct futures ETNs certainly are not the way).

Other than during the massive vol spike in 2020 (arguably a time when you would have most wanted it to TBH), VIRT stock has done a pretty good job of tracking the VIX without – unlike the VIXM and VIXY futures ETFs – any compounding negative roll yield for holding over the longer term.

Question: VIRT has tracked the VIX pretty well, but in 2020 failed to rise to the occasion – ABRTX (another vol beneficiary I have money on) did a lot better. Why?

VIRT vs VIXM?

How is the liquidity and bid/ask spreads for these securities?

How bad is the contango decay? Bad

VIRT vs CBOE?

CBOE also benefited from the volatility in the 2020 March COVID crash like VIRT did, yet – unlike VIRT – CBOE’s price went down with the market during the crash. Why?

We can see here that VIRT benefited more dramatically, but it does not negate the fact that CBOE’s fundamentals changed for the better during the vol in March 2020. One explanation I have for this apparent mismatch in price vs earnings change off the top of my head is that CBOE ($13BB) is much larger than VIRT ($2.7BB) and is (thus) a larger component in various market index funds (CBOE is 0.03% of SPY, while VIRT if 0% of SPY). It is thus kinda ironic that CBOE – which sells the VIX volatility index products – is unable to really benefit from any actual vol because of it being dragged along by the indexation forces that vol benefits from.

I see it like this: If there is short term vol in the markets, both CBOE’s and VIRT’s economics benefit, but only VIRT’s price reflects that while CBOE’s price has to recover along with the rest of the indexes, thus making CBOE and worse vol hedge that VIRT. If there were ever a crash followed by a longer term depression, both CBOE and VIRT’s volumes would dry up, but at least with VIRT you would have the opportunity to get out at a higher price once you realized that the vol was started going down with the market and no new QE had yet been announced, since VIRT is the only one whose price would actually rise in the initial volatility, whereas CBOE’s economics would also benefit but not be reflected in the price and would not even recover to price in the benefits of the initial vol afterwards because of the reduction in volume in this scenario. Thus — in the capacity as a volatility hedge and beneficiary — I would say that VIRT is the better.

VIRT vs FLTDF?

https://brighttax.com/blog/us-expat-taxes-americans-living-netherlands/

VIRT vs TLT?

Question: Is there a case to be made that a market maker’s returns should be similar to a UST? A lot of Virtu et al’s inventory is hedge via holding USTs and other high grade bonds, is it not?

In any case, we can examine a few market dips (SPY in black) to see how VIRT (yellow) compares to TLT (blue) as portfolio insurance. Here we have the dip at the tail end of 2018…

Here we can see how VIRT and TLT behaved in the crash in 2020…

And we can see VIRT over its lifetime vs TLT

From this last chart, we can see that VIRT basically acts like a more volatile UST in terms of volatility insurance, but I’ll say this: VIRT trades at a higher yield than the 10 and 20yr UST ETFs, does not suffer from the duration risk of possible — and IMO increasingly likely as UST rates scrape their extreme historical minimums — rate hikes (and in fact would benefit from the ensuing volatility), has a higher dividend yield, and — also unlike TLT — is a beneficiary (or at least much less of a victim) of inflation in general (since a greater money velocity would translate into volumes for exchanges).

VIRT vs ABRTX?

https://abrdynamicfunds.com/mutual-funds-3/#tab-2-3

“Using the combined output of several proprietary volatility models, the underlying index (The ABR Dynamic Blend Equity and Volatility Index Powered by WilshireSM) determines an unleveraged, long-only allocation to a blend of equity, volatility, and cash exposures each day.

-The Fund’s exposure to Equity increases in periods of relatively low market volatility.

-The Fund’s exposure to Volatility increases in periods of relatively high volatility.

-At times, the Fund may briefly convert to a full cash position.”

I actually have a significant allocation in ABRTX as part of a volatility beneficiary basket.

One nice benefit of ABRTX is that it’s based on the SPY index ETF, which is exposed to concentration risk in tech – one of the most overvalued segments of the market wherein the 7 of the top 10 companies in the index are tech companies and make up 30% of the index in total. So a bet on ABRTX gets to ride along with tech in a small way and if/when the bubble bursts, gets to benefit from the ensuing volatility.

Risks

Management entrenchment

Founder Viola and Chairman Greifeld together control 86% of the voting power of the company through the class B shares; really the important thing to note is that shareholders of the class A shares that trade on the market get 0% of the voting power. This is totally an entrenchment risk (realized?) as even if Cifu were badly stewarding the company, the un-entrenched size of his individual stake would not matter as shareholders of the class A could even vote him out anyway. It all just depends on what Viola wants, which I suppose is well enough given that he receives no salary compensation from Virtu, so his upside is only linked to the upside of the class A shares.

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/0001592386/000110465921054475/tm2113222-1_def14a.htm#tSOOC

Effects of congressional action on PFOF?

Gensler has mentioned several times that the U.K., Australia, and Canada forbid payment for order flow. Asked if he raises those examples because a ban could also happen in the U.S., he replied: “I’m raising this because it’s on the table. This is very clear.” It’s not the only thing the SEC is considering. “Also on the table is how do we move more of this market to transparency,” he said. “Transparency benefits competition, and efficiency of markets. Transparency benefits investors.”, https://www.barrons.com/articles/sec-chairman-says-banning-payment-for-order-is-on-the-table-51630350595

"PFOF" is horrible because it creates incentives for retail brokers to ensure trading through their platform is as uninformed as possible to maximize how "valuable" flow is to the market makers. There is a reason why Robinhood flow historically attracted the highest PFOF., https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/stop-game-alexander-gerko/

Another risk to VIRT’s business posed by a US ban on PFOF would be that broker-dealer clients would no longer have their TX fees subsidized and would once again have to pay it them themselves and this would likely cause a reduction in volumes.

TBH, if PFOF were made illegal, IDK how badly exactly this would hurt market makers. It would seem that they would stop paying a rebate and the trading flow aggregators would still need to route to market makers to maintain the feature of price improvement on their platforms or would need to internalize their order flow if they wanted to capture the value of the retail order spreads – ie they would need to operate a market making business themselves (TBH IDK that this is likely to happen just from the observation – and I could just be totally missing it here – that there are not already many flow aggregators that appear to be doing this).

As a more cynical take, I’d guess that broker-dealers would just be required by the SEC to make more disclosures to client around PFOF, rather than any outright ban.

Risk of a Knight Capital -esque blow up?

The market maker Knight Capital was a financial services company that specialized in providing liquidity and executing trades on various stock exchanges. In 2012, Knight Capital suffered a major loss due to a software glitch that caused it to make a series of erroneous trades, resulting in a loss of more than $460 million7. This was widely covered by the financial media and led to significant changes in the way that market makers and other financial firms managed their risk8. After the Knight Capital blowup, the company struggled to recover and was ultimately forced to seek a capital infusion from outside investors, merging with another financial firm, Getco LLC in 2013 to form KCG Holdings9. However, the damage to Knight Capital's reputation and financial position was significant, and it took many years for the company to recover and regain its footing in the financial markets.

The fact that KCG was actually acquired by Virtu Financial in 201710 highlights the ongoing — blackswan-esque — technology risk11 that Virtu needs to manage in order to avoid a similar incident.

Are HFT DMMs good for society?

"PFOF" is horrible because it creates incentives for retail brokers to ensure trading through their platform is as uninformed as possible to maximize how "valuable" flow is to the market makers. There is a reason why Robinhood flow historically attracted the highest PFOF., https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/stop-game-alexander-gerko/

What’s with the ownership structure?

This goes back to the entrenchment risk I noted earlier.

Appendix

Founding

https://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/VirtuOverview.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtu_Financial#Organization

https://seekingalpha.com/article/3981765-volume-and-volatility-drive-virtu-financial

Mar 20Feb 2017

Oct 2017 - Dec 2018

Mar 2019 - Mar 2020

Sep 2020 - April 2021

Jun - Nov 2021

This article is just an idea placeholder for something that I’ve already been invested in for a while and am in the process of researching further. In a good amount of cases, my buying process looks like this: I’ll find something I think is interesting, do some base research into the main ideas, put 1x, 1/2x, or 1/4x of a “full” position into something, and add or remove percentage points of exposure as I build or lose conviction in the idea as I look into it further (my thought on this is to take advantage of the unique liquidity of the stock market and get the advantage of lump-sum positioning, so the main risk of getting materially hurt is that something really bad happens very soon after that could have been avoided by further research and I think the probability of this just tends to be low) – letting power series convergence push initial exposure up/down in the meantime (stocks are usually liquid enough that price impact is not a huge issue for the amounts I’m investing). It’s a negative — rather than additive —ess (can’t remember the exact reason I do it this way, but I recall it was from reading something by Paul Enright on portfolio management). This article is mostly just a reprinting of my notes for step 1 of that process – so there is likely going to be things I get just totally wrong about the subject here. Much of this current post is just a consolidation of notes from before making that initial investment and I will update this post in the next few days/weeks to consolidate the remainder of those older notes (I think this is fine since no one but people I know really read these anyway).

*Update 20220613: A much shorter explanation of market makers can be found here: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4517979-what-are-market-makers

(Updated) Can read a bit more about dark pools here: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4505701-what-is-dark-pool-trading

For a bit of context, this is the basic standard deviation formula:

This is basically what is means the aggregate spread of data points from the mean (for RV here, that mean would be zero):

https://stats.stackexchange.com/a/85390

http://blog.amarsagoo.info/2007/09/making-sense-of-standard-deviation.html

And also:

ln(x/y) = ln(x) − ln(y)

This is the reason why – I am assuming – they are doing a log difference of returns rather than return values themselves:

https://stats.stackexchange.com/a/221809

So, here S&P is assuming the average day-over-day price return difference is 0% – that is, day-over-day, the underlying index price change is the same (ie. the change in the change in price is zero) – to focus on the actual/realized daily spread in price return levels day-to-day in the lookback window.

I actually don’t know the reason behind multiplying the numerator by the trading days window – I assume it has to do with annualizing the value – or the reason for multiplying the whole standard deviation term by 100, but it’s enough to know that RVt is directly proportional to the standard deviation.

I recently saw this article that has a better explanation of RV: https://www.wallstreetmojo.com/realized-volatility/

Great article on Virtu I learnt quite a bit from it, even after following Virtu for a while.

I wrote an article on Flow Traders https://myinvestmentjournal.substack.com/p/flow-traders-buy-this-antifragile