($FRMO) FRMO Corp: The Most Important Things - Part 2: The Fed is going to let inflation run hot

What needs to go right, else nothing else matters (for FRMO and many other inflationista bets)?

“I think the key ingredient of that is focusing on what is the risk you’re taking. I think a lot of people get in a lot of trouble because they do a transaction and they don’t understand what the risk they’re assuming is when they do the transaction. What he taught me more than anything else was, look at the deal and figure out where is the vulnerability? Where is the assumption you’ve made that has to be right in order for the deal to work? [...] The only real issue was, could you or could you not rent the office space? If you could, the deal was going to work. If you couldn’t, all the other stuff didn’t matter.” — Sam Zell on learning from Jay Pritzker

What are the top things that render all other issues irrelevant for whatever current problem you’re looking at? IMO, the most important things for the success of FRMO, the things that need to be true for the investment to work out in the long term1 are (in order of what topics I think are the least to most opaque — so really it may be more responsible to start from the bottom and work upwards (though it’s also roughly ordered from most to least important)) — are...

That the commod shortages that are being bet on at FRMO — mainly oil — are "structural" (mentioned in HK's 4Q2021 and 1Q2022 commentary reports), which in the context of HK/FRMO articles or transcripts kinda hints that demand destruction is not a long term concern, but rather that the supply vs the world's non-discretionary demand is so far apart as to not be affected by the any monetary policy in the long run. FRMO’s main oil holding is $TPL.

The Fed is trapped and can't / won't / might not actually want to raise rates in a too-serious way to kill inflation — and even if they do raise rates it would create a economic and political situation wherein those rate hikes would not last long or… see #1.

FRMO’s main BTC moon-shoot thesis works out — management recently mentioned in the 3Q2022 CC that crypto (not TPL or oil) was their most important investment view. While they hold a lot of various little call options that could end up paying out significantly in the longer run, FRMO’s main BTC holding is though $GBTC.

BTC is not going to get outlawed and that Tether does actually have all the USD required to back each USDT (which is important since USDT makes up 60% of BTC's inflow volumes at the time of me writing this (20220501)) — ie. that Tether is not some scam to pump the market cap of BTC using USDTs that are not actually backed by any USDs or other asset.

Here I cover what Stahl and Bregman et al at FRMO/HK have said on these topics as well as some notes from other POVs on the subject.

Will the Fed let inflation run hot?

While not really my game of choice, the macro component is an important part of FRMO’s inflation thesis, so is not something I could just skip over. That being said, it’s certainly not something I’m super comfortable in, but I can still reasonably understand and interpret the main arguments for and against the idea of a coming long-term inflation cycle and I present some of those main arguments here.

Yays

FRMO/HK

HK Commentary 2Q2020

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Quarterly-Commentary_Q2-2020.pdf

(See section: “The next question is still on inflation vs. deflation. The average American, or politician, or investor currently looks to the reported CPI number, that 2% figure, and those still do not reflect meaningful inflation…”)

HK Commentary 2Q2021

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q2-CVALUE-Review_FINAL.pdf

Debt vs. GDP; Yes, Also Inflationary

[...]

Our current era’s massive debt accumulation [since the 1980s] did not fund new productive capacity in the nation’s factories and research facilities; it did not purchase robust economic growth. And there appears to be no expectation of a dramatic decline in spending.

Ie. Unlike the gov funding in post-WW2 US, this new round of gov debt spending did not pay out w/ a higher GDP – in fact Debt/GDP went way up. Like when a company invests in growth via debt, but ends up w/out the desired revenue increases

One can speak of the economy outgrowing the debt, but during the very favorable past 10 and 20 years, GDP expanded at only a 3.7% rate. No one seriously suggests that it will be more robust in the next 10 years than in the last 10.

Debt grew by ~8%/yr while GDP – read as total country revenue – increased by 4%/yr.

HK Commentary 4Q2021

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q4-2021-Quarterly-Review_FINAL.pdf

Total debt in the U.S. is now $85 trillion. That’s everything from Federal and local debt to auto loans, credit cards and mortgages. The average interest cost is 4.1%. What if the Fed were to let rates rise by 2% points. Doesn’t seem like a lot. It would just bring the 10-year yield to 3.7%. My goodness, it was 6% just ten years ago. So what would happen? Here are two ways to see what the impact might be like. This is exceedingly simplistic and certainly wouldn’t pass muster in any econometrics class.

Just for simplifying purposes, though, let’s say that the 2% immediately filtered through all the different types and maturities of debt. That means that the entire country experiences an increased interest expense burden of 2% x $85 trillion of debt, which equals $1.70 trillion. What does that even mean?

$1.7 trillion of additional interest expense would reduce our $23 trillion of GDP by 7.4%. A significant recession is a -3% GDP contraction. The Great Recession of 2008/2009, following the subprime mortgage crisis, which was a true financial crisis, was a -5.1% contraction.

To make it even more relatable, let’s say the additional $1.7 trillion of interest expense were somehow all allocated only to oil, like a special excise tax. The U.S. consumes roughly 20 million barrels of oil per day. That’s 7.3 billion barrels a year. If we pay an additional $1.7 trillion per year for that oil, that would be an additional $232 per barrel. Since oil is about $85 now, that would be $317/barrel oil.

The economy couldn’t handle it, at least not at an acceptable political cost to those who would be identified with that policy decision. So, some believe that the Federal Reserve won’t raise interest rates, irrespective of what they say about it (more about that later). But, in order to not raise rates, the central bank needs to continue to purchase bonds, to thereby suppress yields. And to do so, it must continue to print more money to buy the bonds.

Which is why the central bank’s (any central bank’s) standard recourse is to play out this self-reinforcing monetary debasement game for as long as it takes to ‘grow’ out of the problem. And it can grow out of the problem. It’s just that it comes at a cost, a long-term economic and social cost as opposed to a short-term political and social cost.

That cost is monetary-based inflation, or currency debasement, and its consequences.

HK Commentary 1Q2022

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q1-2022-Roundtable-Discussion-for-Website_FINAL.pdf

You really have to talk about the entire debt for the nation. Add in everything from a credit card to a student loan, to a municipal bond, and that number exceeds $89 trillion. That gives you a basis to understand that if interest rates are going to go up one percent—and I only mention one percent because it’s an easy number to work with—that means there’s another $890 billion of debt service, call it $900 billion for ease of calculation, in a $24 trillion economy. That’s a lot. If it were two percent, just to pick a number without predicting any particular scenario, that’s $1.8 trillion of extra debt service. I don’t think the country can handle it.

My main issue with Stahl’s argument is that it, while articulate, does not seem very precise about certain things:

Management appears to assume that all (or the vast majority) of the total collective US debt is essentially of short maturity, recurring, and non-discretionary. What is management looking at to make this determination?

I’d like to see them break down / explain their thought process in a bit more detail regarding by what economic logic additional additional interest expense is seen as being “taken out of” or reducing GDP when illustrating their politically-unacceptable-contraction in their 4Q2021 Fed-is-trapped thesis.

If the issue is a debt death spiral sans the Fed stepping in with money printing for tax receipt deficits on interest expenses and entitlements, then what is management looking at to determine that new UST issuance from the US Treasury could not be made without moving rates — and thus causing a spiral that thus needs to be preempted by Fed support — to fund these deficits or that taxes could not be raised sufficiently to cover the deficit?

UPDATE 20221101: The Horizon Kinetics POV on the Fed’s inability to fight inflation via interest rates is directly addressed in the 3Q2022 HK commentary here, section “Presumption of the Day: The Fed’s Interest Rate Increases Will Suppress Inflation”: https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q3-2022-Review-1.pdf (pg.4-14)

This idea that the Fed is going to have to let inflation run hot because of the significant incremental interest expenses that would come from increased interest rates is something that I’ve also seen — and IMO, described in greater detail (likely owing to the vastly greater number of podcasts etc he’s been on discussing this topic) — from research firm Forest For The Trees’ (FFTT) Luke Gromen…

FFTT — US meets EM balance of payments crisis

I think Gromen represents a pretty good approximation of Stahl’s views on monetary inflation and where the global macro picture generally is heading2. It’s essentially that the US is a twin deficit country (national trade deficit + government spending deficit) facing a balance of payments crisis (being unable to cover debt servicing and critical imports and entitlements) — and that it will do as all other countries (see Argentina or Turkey) in similar situations have done: print the dollars to monetize the debt (ie. inflate it away).

The basic premise goes like this:

Starting with some assumptions: * "True" Interest Expense (TIE) := Federal interest expense + Federal entitlement expenses ==> Tax Receipts / TIE ~= 80% ==> Deficit exists in tax receipt coverage of Federal TIE obligations. * Tax receipts are highly correlated to asset prices. * Congress controls the Fed So, if Fed raised rates to crush inflation (w/out monetizing debt) ==> high volatility (to the downside) in stock and bond markets would ensue ==> Tax receipts will fall along with asset prices. TIE could rise as well, since a large percentage of US Federal debt is of maturities less than 1yr, which would be rolled over into these higher rates. ==> US would have to default on it's TIE obligations ==> Raising rates w/out debt monetization is outside of the Overton Window of politically viable options ==> Fed will ultimately need to pivot to "printing the money" to be the buyer of last resort of USTs to cap yields if it wants to raise rates (ie. if Congress needs to sacrifice the Fed's balance sheet or the bond market, the Fed's B/S loses) ==> Fed needs to maintain monetary inflation (and financial repression) for a prolonged period to normalize Debt/GDP (via inflating GDP) until it reaches a point where rates can be raised without risking a US default on its TIE obligations. You'll know the great inflation is on when the Fed implements some form of yield curve control (YCC) -- likely attempted quietly, under some other name or acronym. Inflation rates may rise or fall, but ultimately the Fed is not going to raise rates above the inflation rate -- and so inflation will continue on.

This argument is similarly supported by Russell Napier:

Just like after World War II, Napier believes that governments will pursue a policy of financial repression in which the interest rate level is deliberately kept below the rate of inflation to get rid of the high levels of debt.

********** UPDATE 20230729: This appears to be the opinion shared by the Deputy head of the IMF, Gita Gopinath, as well:

Central banks must accept the “uncomfortable truth” that they may have to tolerate a longer period of inflation above their 2 per cent target in order to avert a financial crisis, the deputy head of the IMF has warned.

Gita Gopinath told the European Central Bank’s annual conference in Sintra, Portugal, that policymakers risk being faced with a stark choice between solving a future financial crash among heavily indebted countries and raising borrowing costs enough to tame stubborn inflation.

“We are not there yet, but that is a possibility,” Gopinath told the Financial Times before her speech. “In that environment is when you could see central banks adjusting their reaction function and saying ‘OK, maybe we tolerate inflation being higher for some more time.’”

**********

There are some questions/concerns I have about this whole idea:

Debt monetization (basically, QE) only creates bank reserves (which are near an all time high for as far as FRED data goes back) — not bank deposits — and these are not necessarily spent/circulated in the real economy, but rather used in general portfolio rebalancing by commercial banks that may be allocating to collateral other than direct lending to consumers/businesses which is the mechanism that actually transfers those QE dollars from banks into the pockets of mainstreet participants. So, it’s not totally obvious that QE really affects the world’s purchasing power and you can find many macro articles on why traditional money measures like M1 or M2 are not meaningful for understanding true monetary expansion (yet may still be being used because of, IMO, an accessibility bias).

UPDATE 20220712: Management actually kinda addresses this issue in the HK Q2CY2020 Commentary (word-search for the line “The government can print as much money as it wants, but if it is not circulating, then it is not causing the desired effect. The velocity of money seems to point to a non-inflationary environment.” in the “Inflation Questions” section), though side-skirts the issue of whether or not they should be using M2: “The difference between now and the last ten years is as follows: The last ten years were, I would say, the high tide of not just indexation, but of outsourcing: the outsourcing of labor, the outsourcing of manufacturing. So, that in itself was a deflationary trend: through the mobility of labor, a global labor arbitrage. And I just don’t see that continuing; it’s coming undone even as we speak. Secondarily, what was the world thinking about in 2007? Well, we know, because it’s in retrospect. They were thinking about the industrialization of China, partially because even then the global outsourcing movement was happening, and there was a commodity boom in 2006- 2007, which lasted into the first couple of months of 2008. It was anticipated that the emerging market economies, led by China, would demand tremendous quantities of commodities, and they were right. The trouble is that all the commodity companies in the world – we could talk about gold companies or oil or iron ore or others – were able to raise enormous quantities of capital and engage in a lot of development projects and collectively fill whatever the incremental demand for the commodity was. So, just go back 10 or 14 years and look at how big the energy sector was in the junk bond market, at how much equity issuance there was in energy-related projects. Then the demand for those commodities fell. That meant oversupply, and all the producers had to cut their production. And ever since then, the prices have stayed too low for the producers to make a return on new investment, and they reduced their capital expenditures and stopped replacing their reserves. So that has been another deflationary pressure ever since, beginning in 2008 and various years thereafter.”

FRMO management constantly points to M2’s exponential growth as a proxy for illustrating monetary inflation. Currently, M2 velocity is near all time lows and my understanding is that of the bank

FRMO management constantly points to M2’s exponential growth as a proxy for illustrating monetary inflation. Currently, M2 velocity is near all time lows and my understanding is that of the bank reserves that are created from QE, only a very small amount of that makes it into the real economy via the credit creation mechanism of direct lending (we can actually see that total US credit growth has been at a much lower trend ever since 2008). I’d like to see management comment on the possibility that M2 — while a fine measure for the "monetary base" — is not an effective measure of circulating "monetary supply" expansion or consider incorporating a larger composite of metrics to justify the currency debasement thesis (just as an example, revolving credit lines are functionally similar to money but not accounted for in M2). In June 2000, Alan Greenspan mentioned — in reference to monetary policy — that "The problem is that we cannot extract from our statistical database what is true money conceptually, either in the transactions mode or the store-of-value mode." How can the Fed be providing any accounting of how much money there is (eg. vai M2), if they don't even know what money is? Is there a risk of an availability bias of information here? While the M2 monetary base has certainly been increasing, this does not mean that the current monetary supply is much lesser or greater than in previous times — and again, referring to the money creation privilege of commercial banks, total US credit growth has been way below trend since 2008.

UPDATE 20221018: I asked about this at the Q1FY2023 FRMO CC (I’m Questioner 2). Not totally sure what to make of this at the moment, but you can see Stahl’s response there for yourself. A snippet from the response: “Velocity is supposed to measure what

people are doing with their money. The reason the reported velocity is low is because the spending of the three governments—federal, state and local—represents 45% of the gross domestic product. Because it goes through the Department of Treasury rather than the banking system, and despite that it’s so huge and such an important part of velocity, we’re not picking it up; we’re not measuring it. The money velocity figures that are reported look at what the people are doing. Now, it’s still a lot of money, but we’re not looking at what the government’s doing. […] As far as reaching a conclusion, it’s just that you’ve got to get the right data, and that has to include what the government’s doing. We can’t ignore that 45% of every dollar that’s spent in this country annually is spent by one or several of those branches of government.”

Gromen does not seem to dwell too much on the advantages that the US as in this historical reasoning by analogy vs other twin deficit countries that make it pretty unique from other countries: It is the source of the world reserve currency and is the largest military power in the world — this can’t not play into the political dynamics that will guide the trajectory of where the situation heads, IMO.

This lack of coverage of TIE by tax receipts is a situation that has existed for some time now, so IDK exactly why raising rates would be an issue this time around as the data shows that the TIE coverage situation hasn’t stopped the Fed from raising FFR above inflation rates in the past. (See the historical data here and here).

UPDATE 20230211: Though —looking at this again after reading the HK 4Q2022 Commentary— it could be argued that ‘this time is different’ in that, now, rates are in the low single digits, while the “true interest expense” is around where is was in the 1980s when rates were already hiked to the low teens; hiking at this point is would indeed lift those expenses to unprecedented levels as debt is rolled over to the new rates (my understanding is that ~50% of US debt has a maturity of less than 3yrs). If the red and green lines, below, want and rematch of the 1970s, how high is the blue line going to go this time?

Some interviews with Gromen on his inflation thesis can be found here:

I think it's the beginning of a structural inflation that's going to last many years. I should probably say thanks for having me back on to start. But the reason I think it's structural lasting for many years is I think if you look at a lot of the key factors that have been disinflationary over the last 20 years, 30 years. A lot of them are going in reverse.

This definitely reminds me of Stahl’s 40yr commodity/inflation depression thesis mentioned in the previous post re. deglobalization — though Gromen also includes boomer-era tax differed retirement accounts beginning to make good on their required minimum distributions in the basket of inflationary trends.

Going further, Gromen goes on to say…

[E]verybody for 40 years has been conditioned that once we see these types of inflation, the Fed steps in to fight the inflation. And the problem is, is that there have been no instances in the last 40 years, where the Fed has begun a tightening cycle, where the US couldn't even afford to pay its interest out of tax receipts. And that's the case now, if we look at true interest expense, again, which is the Treasury spending plus entitlement pay goes, and so it leads to this conclusion that if the Fed tries to tighten, what you're likely going to see, before very long is a decline in tax receipts. If the Fed puts us in a recession, and we're obviously seeing significant slowing already. You're gonna be looking at tax receipts that are already below true interest expense, and probably would start falling further, while the true interest expense [Treasury spending plus entitlement pay-goes] would probably rise because of the interest rate going up.

But what this means is that the Fed's choice now is binary. Unless the Fed is willing to tighten, and then stand aside as the US government does not have the money to pay interest expense, true interest expense without the Fed's help, then basically the only choice is the Fed keeps helping, and the Fed keeps monetizing as they've done for the last 14 or 18 months. And so that is, I think, you know, arguably, when I had that list of structurally inflationary factors before, arguably the most inflationary factor is this dynamic that the US government needs inflation to run hotter than it is today to inflate tax receipts, to much higher nominal levels of GDP to much higher nominal levels, so that the US government can cover its true interest expense.

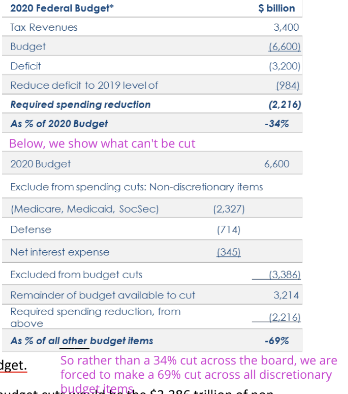

Steve Bregman mentions in the 2Q2021 HK Commentary (“Debt vs. GDP; Yes, Also Inflationary”) HK/FRMO’s reasoning for why why budget cuts are highly unlikely is based on political reasoning due on how much of the budget is composed of entitlement spending: “To reduce the 2021 budget deficit of $3.2 trillion to 2019’s $984 billion, would mean cutting spending by $2.216 trillion. That’s 34% of the $6.6 trillion spending budget. [...] The required spending reduction, from above [budget excluding non-discretionary / entitlement spending], is $2.216 trillion. That means a 69% reduction of every other budget item. [...] If this very simplified reasoning is correct, that raising interest rates at this late stage would be self-defeating, that there is no solution that way, then perhaps the Federal Reserve has already privately determined that it will not raise interest rates. The remaining pathway is for the central bank to inflate its way out, to continue the money supply increases, so that eventually debtors can pay back their fixed obligations with cheaper, more plentiful money. Which, after all, has been done throughout time. [...] Who can know how this will develop? But a more fitting term than transitory might be structural. Which isn’t good for the value of money.”

Back to the Gromen interview:

And then we can get into defense, education, labor, national parks, veterans affairs, everything else they're spending money on. But right now, the US government doesn't even have the tax receipts to cover true interest expenses. And so to me, it doesn't suggest they can't or won't raise rates. It just suggests that if they actually withdraw liquidity, it's probably going to be pretty volatility inducing, and really, really bad for risk assets pretty quickly. And then I think the Fed will very quickly have to reverse track, which I think will be very inflationary.

[...] But I think the odds that the Fed tightens and then stands aside as rates go up, and stocks go down, and the US government has to decide if it wants to keep funding defense or send checks to baby boomers, I think there's zero chance that happens. And if you have two options. And one of those options has zero chance of happening politically and economically for that matter, then you're left with whatever's left, and whatever's left is [that] they’re going to print the money. And so I think the MMT crowd is exactly right. I think that's what's going to happen. And I think the reason the MMT crowd suddenly has an ear in Washington, is I think there's enough people in Washington that are looking at the math, and they can't make two plus two equal $6 trillion. And they're going okay, well, how do we make two plus two equals $6 trillion? And, you know, the MMT crowd comes in and says, hey, well, you could, you could print 599,000,000,000,000, or whatever that number is. and Washington goes, okay great. MMT sounds awesome.

[...] Does the Fed want the release valve to be yields or does fed want the release valve to be its balance sheet, and the only political and economically palatable choice is for the release valve to be the Fed's balance sheet. And at that point you'll just see and what it'll just start feeding on itself. And the Fed's balance sheet will go 8, 15, 25, 30 trillion, whatever the number is. Inflation will officially go from five to seven and will be running at 20 or 30. And after, you know, five years of 20%, inflation. US debt-to-GDP will be back down to 70% from 130% as GDP skyrockets, while interest doesn't and you know, bonds will go from buying you filet mignon to buying you dog food. And you know, a bond and that'll be that will then be the position where the Fed can raise rates, again. They can normalize policy. And I think that's the prescription.

https://www.grant-williams.com/podcast/0028-luke-gromen/

Here Gromen goes over his thoughts on the dueling interests of financiers/banker (who want to retain the dollar’s – and globalization’s – status quo) vs industrialist (who want to remove/reduce the dollar’s status as the world reserve asset and to reshore manufacturing in America)

Or the Fed has to basically re-up QE into an inflation spike to continue to finance these things that defense, entitlements, treasury, interest and treasury spending, these aren’t cuttable. So ultimately remember that defense report that we talked about where they talked about the excess Chinese buying of treasuries undervalued the Yuan, overvalued the dollar, deindustrialized, the US made the US defense industrial base weaker vis a vis China. And we need to stop this, this reverses that. All of a sudden closing the FX reserves window, no one’s going to buy FX reserves anymore.

Even if they just buy less, forget about not buying them anymore, they buy less. That means the Fed’s got to buy more, which means the Fed’s going to have to do more deficit financing via the printing press. And we know what that did to the dollar, what that did to inflation, because we saw it from 2020 through 2021 and even forward. So the bad news is if you hold a lot of bonds, it’s a sea change. It’s the end of a 40 year bond bull market on a real basis.

Nays

Santiago Capital — Dollar Milkshake Theory (DMT)

https://www.macrovoices.com/podcast-transcripts/998-brent-johnson-us-dollar-still-not-crashing (He even weighs in on BTC and Tether in this interview, interestingly)

From the various MacroVoices articles:

I’ve answered this many times before and will attempt to do so (somewhat briefly again now). The milkshake theory basically says there is a supply/demand mismatch with regard to dollars in the world.

My argument has been that this fact, along with others such as the institutionalized effect of the GRC, the design of the dollar payment system, the US military and the largest & deepest capital markets on earth will drive capital flows to the US over the next few years.

So on a RELATIVE basis to the ROW, we will be able to weather the storm better than others. I have never said it would be easy, have never said we wouldn’t get hit, never said we wouldn’t fall.

It seems like the argument is that monetary policy is so bad all over the world ATM that the USD remains the best house in a bad neighborhood.

My basic understanding of the DMT is that there is a global debt crisis — Murray Stahl actually mentions this in the HK 1Q2022 Commentary (see "Is our current condition stagflation?") where basically the issue is too much debt taken out to fuel topline growth (ie. GDP) (as opposed to, say, something more analogous to NOPAT or FCF), though unlike Stahl's inflation POV Santiago is claiming a disinflationary trajectory — and as that debt becomes unmanageable there will be a scramble for liquidity/dollars to service that debt or as a safe haven for capital from the heightened level of perceived risk in other assets around the world.

But the US is the global reserve currency. So a lot of that debt has taken place in dollars and that puts a lot of demand under the dollar. You know, so despite the fact that we've been printing a lot, other countries have been printing a lot, too. And so I've coined this term that they've created this milkshake of liquidity.

And I believe when we enter this currency crisis and this debt crisis, I believe the dollar will, for many reasons, be the last man standing. And I think as that happens, the dollar will suck up the global liquidity, hence the dollar milkshake. Now if we enter a global monetary crisis, and a global sovereign crisis, or a currency crisis, and the dollar falls rather than rises. Then I will hold up my hand again and say, you know what, the theory was wrong, I got it wrong. But until we get into that crisis, and see how that crisis plays out, we just don't really know.

[...]

And then I think in the years ahead that we're going to go much higher in both the S&P and the Dow. Again, you've heard me talk about this before Erik. I think that we're going to enter a period of sovereign debt crisis.

And I think when sovereign debt starts to get sold, those funds are going to look for a home. And I think one of the biggest and most liquid markets on the planet is US equities. And I think that will get fund flows. And I think that equities have the potential to go much higher than anybody believes possible. Now, again, I just want to caution, that doesn't mean you need to go out and go all in on equities right now, here today. I think we're going to get a pullback, but for anyone who thinks that we're going to go down to 200 on the S&P and stay there for 10 years, that's not my base case. I don't think that's going to happen. Can't rule it out but that's not what I'm planning on. I think we're gonna see much higher levels in equities in the years ahead.

[...] Just the other day, you know, GDP was forecast to come in at like 8% and it came in at a little over 6%. So you're already starting to see some of these economic growth prospects to get pulled back. In addition to that, you know, you've seen a number of these commodities like copper had a huge move, lumber had a huge move, but you know, that those have pulled back anywhere from 5% to 20%. And so some of these really, really inflationary, you know, commodities, you're starting to see a pullback now. I think we have to kind of wait and see how the next six months ago. Again, I tend to believe that the biggest risk near term is deflation [ie. and thus a scramble for liquidity and dollars] rather than inflation.

So he seems to be in the disinflation/deflation camp w/ Jeff Snider et al — thinking that there is a liquidity issue in the system (and, per Snider, the bond market yields curve are showing this via their persistently low yields on the back end of the yield curve). Like Gromen, he sees the same debt problem, but unlike Gromen, thinks that it ends in a sovereign debt crisis (ie. that the Fed is not going to / not be able to sufficiently step in to monetize the debt to avoid this) — essentially taking the Fed’s side of the bet in the rate-hike, inflation-crushing game of Chicken that the inflationistas like Gromen seem to be playing.

[...] I'll tell you, Erik, the bond market certainly doesn't think that inflation is raging. You know, if you look at this chart, you can see that, you know, other than the pandemic, when we had a massive move lower in yields, you know, last year, and then a huge run up.

[...] I again, because I believe that, you know, we're going to move into kind of a disinflationary environment and potentially even a deflationary environment. I am not participating fully or aggressively, for lack of a better word in the commodities. I think a lot of people are just convinced inflation is here, and are going all in, quote unquote on the commodity trade, and I'm just not there yet.

[...] That said, the one area of commodities where I am extremely interested and in going and looking to add positions on pullbacks aggressively is the soft commodities. [...] And part of the reason is, regardless of what's going on the economy, you still got to eat, people still have to eat. [...] And I think to to the extent that people are looking to add some additional diversification to their portfolio or another way to play, perhaps the devaluation of fiat currencies, I think the agricultural commodities might be a better way to do it than just the general industrial commodities.

(BTW, per that last slide, I would really like to know what a “Global Macro/Volatility” asset allocation looks like — aside from taking the downwards path dependency and negative roll yields of VIX futures ETFs on the chin).

Per NIRP for USTs, Santiago leans more along the lines of other political analysts I've read — that is, the world reserve currency will not go negative interest rates:

So I kind of depart from a lot of my, I guess, quote unquote, friends in the deflationary camp on this, because I personally don't think that the US Treasury is going to go negative. Now it could, it will, if it happens, it will not shock me. But that's not my base case. Part of the reason is, I think, in a really deflationary environment, you know, the market might take the negative under a very short period of time. But then I think that would force some kind of a reset for lack of a better word. So I don't think that we would have a multi month or a multi year scenario where the global reserve currency is at a negative rate. Now, we've had negative rates on, you know, Swiss and other European and Japanese rates for years now. And that's a little different, because it's not the global reserve currency. I can't, I don't necessarily think that rates are going to go negative in the US. And if they do, I wouldn't expect them to stay there very long.

Ultimately the DMTists like Johnson and inflationistas like Gromen and Stahl are both betting on a global debt and liquidity problem coming to a head, but where the inflationistas like Stahl are betting on a “soft“ default in the form of / masked by inflation being allowed to run above real rates for a prolonged period (and thus devaluing the dollar), the DMT crowd are predicting a real, hard, global default situation (causing a deflationary scramble for dollars).

Snider — The eurodollar system and the bond market isn’t buying it

Similar to the DMT disinflation premise from Santiago, I think Snider’s POV can be summed up thusly: The bond market is loudly saying that there is something going on with liquidity under the covers of the Eurodollar system that is causing bond yields (which act inverse to price) to remain stubbornly low (ie. price remains stubbornly high (ie. global demand for conventionally safe assets remains high)) despite the current narrative of inflation no longer being transitory. That is, the bond market is betting that rates are going to be coming back down soon (ie. that there is going to be another recession that will cause the Fed to reverse course on their current rate raising inflation battle).

I think it’s most informative to see Snider’s ideas presented in the form of the debate here (as it gets him to answer certain questions he otherwise glosses over in his writing or clarify certain things he means). It should be noted here that — while Stahl and Gromen do not preclude the possibility of a recession in their macro outlooks (ie. stagflation) — Snider’s POV is specifically deflationary.

********** UPDATE 20221104: Even Snider now believes that the Fed is looking to pivot, though not necessarily backing down on his idea that the UST market is signaling an incoming deflation bust. **********

********** UPDATE 20230523: This article on central bank collusion at the instruction of the US Fed to manipulate global interest rates mid/post-2008 also seem very relevant to some of Joseph Wang’s arguments in this video. **********

Hugh Hendry

Another macro guy I follow from time to time is Hugh Hendry, who is also calling for UST yields to drop — the general thinking being that the Fed is going to hike the US into a recession. While he and his blog site have the appearance of someone selling timeshares to 30-somethings, he is certainly well credentialed and respected by many other macro thinkers so far as I’ve ever seen, so just thought to add him here as a little bit of extra flavor.

At this point, I think it is also important to remember Seth Klarman’s “Margin of Safety” passage warning against making investment decisions based on macro forecasting in general:

“By way of example, a top-down investor must be correct on the big picture (e.g., are we entering an unprecedented era of world peace and stability?), correct in drawing conclusions from that (e.g., is German reunification bullish or bearish for German interest rates and the value of the deutsche mark), correct in applying those conclusions to attractive areas of investment (e.g., buy German bonds, buy the stocks of U.S. companies with multinational presence), correct in the specific securities purchased (e.g., buy the ten-year German government bond, buy Coca-Cola), and, finally, be early in buying these securities. The top-down investor thus faces the daunting task of predicting the unpredictable more accurately and faster than thousands of other bright people, all of them trying to do the same thing.”

… And I’d note that Hendry himself admits in an episode of his Acid Capitalist podcast that his 15yr CAGR, when he was running his Eclectica Asset Management, was ultimately about average (around 7%/yr)3 —this is not to knock Hendry, but just including this to further illustrate the dubious value and difficulty of taking these kind of macro analyses at face value or making decisions based directly on them.

Why is the bond market not buying inflation?

Calling back to Jeff Snider, if there is some prolonged inflation cycle coming, why is that not showing up in the bond market yield curve? Snider would say that it’s because QE doesn’t even work — or may even be deflationary. Stahl thinks the bond market is just totally controlled by the Fed – ie. that the bond market is not predicting anything:

https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2022_Q3_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

47:19 So, even though when a bank gives credit, they’re not printing money with a literal printing press, they are creating money, they are creating liquidity. Now, I think the last part of your question is about what the bond market is predicting. This is the only point where I’d be a little strident and say, I don’t think the bond market is predicting anything. Why not? Because the bond market is managed. I don’t even think it should be called a market any longer. The size of the Federal Reserve balance sheet alone is over $9 trillion. Then you have the banks and how many Treasuries they hold—they work hand in glove with the U.S. Treasury. Then you have the various indexes that buy bonds just to hold them; and they’re required to be price indifferent – so long as they have net inflows, they buy and continue to hold. So, what is the bond market? It’s comprised of indexes, and indexes have been the marginal trade for many, many years. They’re not active managers making, in part, assessments of how much money is in or will be flowing into or out of bond indexation. I wasn’t anticipating the question, so I don’t have that figure readily at hand, but it’s a huge number.

So, I don’t think bond prices are predicting anything. I just think they are just reflecting a policy of managing the interest rate. If you go to the Federal Reserve website, you’ll find an endless stream of articles and discussion points about how that’s exactly what they’re doing. I haven’t even mentioned the central banks of other nations that also own the U.S. Treasuries. In which case, I should add the International Monetary Fund and also the Bank for International Settlements. So, to say that bond prices reflect a free market clearing price, that the bond market is making a prediction while the world’s central banks, with their vast balance sheets, are doing everything they can to control rates, I just don’t think that’s the right way to look at it. But that’s just me, but I hope you can see why I don’t even regard the bond market is predicting anything.

Here’s a quick article — just a 2min listen if you don’t want to open the link in Firefox private browsing mode — on the same subject from the WSJ: https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-the-fed-rigs-the-bond-market-inflation-yields-financial-crisis-treasury-11637165868

On the other hand, here again we have Jeff Snider on Eurodollar University rebutting that very same WSJ article:

(Check the links in the description)

IMO, the idea – proposed by Stahl et al – that the Fed controls the global bond market is an extraordinary claim and thus requires extraordinary proof or at least a more detailed explanation than Stahl’s.

One thing I’d have an easier time believing is Joseph Wang’s interpretation that the bond market is just a market of people (read as: humans — and likely many passive indexes/ers) buying/selling bonds that may have institutional / gov regulatory drivers forcing buying (eg. Basel III regulations) in addition to individual collective decision making and that – in this case, using HK’s “End of a deflationary era” inflation thesis – that market is just wrong in this case (in a similar manner to the Fed’s expressed view of “transitory” inflation).

Would a rate-hike recession actually be good for the economy in the medium/long run?

“[T]o avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely (ie without limit), to solvent firms, against good collateral, and at ‘high rates’”, Walter Bagehot

Lastly, is it possible that a rate-hike-induced recession could actually be a positive, creative destruction event for the economy? As Snider mentions in his debate with Joseph Wang, raising rates incentivizes growth from the credit supply side (vs the demand side with lower rates) as banks will seek out solvent businesses that they can lend to at these higher rates. Given that human demand for consumption is basically limitless, this does actually make a good deal of sense to me to focus on the supply side here.

You can see an article from the Fed directly addressing Bagehot’s quote above, here: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/madigan20090821a.htm

Interestingly, they seem to dismiss Bagehot’s prescription of “at high rates” for their own interests “in light of practical considerations, and that application is not necessarily straightforward” — and maybe they’re right, I’m not a macro guy.

That being said, I do talk about this a bit in a previous post on the merits of a cash allocation in a investment portfolio:

My previous post covering the commodity supercycle component of FRMO’s investment positioning thesis can be found here:

Note this is not including the various small call-option type bets they have such as MIAX, Winland Hld., their crypto mining operations, and Diamon Std.

Though note that Groman appears to subscribe to Zoltan Poszar’s Bretton Woods 3.0 thesis re. the ultimate destination of the structural inflation he foresees, whereas Stahl has directly disputed this idea.

The episode was “Hedge Fund Masterclass - Make Profits Not War” (full story starts around 00:35:31 to around 00:46:45); it’s hard no to sympathize with the difficulties and self-doubt of running a non-permanent-capital vehicle with idiosyncratic ideas that Hendry implicitly mentions in the story. In any case, the fund no longer exists, so it’s hard to find more information about it.