($FRMO) FRMO Corp: The Most Important Things - Part 1: Long-term commodity shortage is coming

What needs to go right, else nothing else matters (for FRMO and many other inflationista bets)?

“I think the key ingredient of that is focusing on what is the risk you’re taking. I think a lot of people get in a lot of trouble because they do a transaction and they don’t understand what the risk they’re assuming is when they do the transaction. What he taught me more than anything else was, look at the deal and figure out where is the vulnerability? Where is the assumption you’ve made that has to be right in order for the deal to work? [...] The only real issue was, could you or could you not rent the office space? If you could, the deal was going to work. If you couldn’t, all the other stuff didn’t matter.” — Sam Zell on learning from Jay Pritzker

What are the top things that render all other issues irrelevant for whatever current problem you’re looking at? IMO, the most important things for the success of FRMO, the things that need to be true for the investment to work out in the long term1 are (in order of what topics I think are the least to most opaque —so really it may be more responsible to start from the bottom and work upwards (though it’s also roughly ordered from most to least important))— are...

That the commod shortages that are being bet on at FRMO — mainly oil — are "structural" (mentioned in HK's 4Q2021 and 1Q2022 commentary reports), which in the context of HK/FRMO articles or transcripts kinda hints that demand destruction is not a long term concern, but rather that the supply vs the world's non-discretionary demand is so far apart as to not be affected by the any monetary policy in the long run. FRMO’s main oil holding is $TPL.

The Fed is trapped and can't / won't / might not actually want to raise rates in a too-serious way to kill inflation — and even if they do raise rates it would create a economic and political situation wherein those rate hikes would not last long or… see #1.

FRMO’s main BTC moon-shoot thesis works out — management recently mentioned in the 3Q2022 CC that crypto (not TPL or oil) was their most important investment view. While they hold a lot of various little call options that could end up paying out significantly in the longer run, FRMO’s main BTC holding is though $GBTC.

BTC is not going to get outlawed and that Tether does actually have all the USD required to back each USDT (which is important since USDT makes up 60% of BTC's inflow volumes at the time of me writing this (20220501)) — ie. that Tether is not some scam to pump the market cap of BTC using USDTs that are not actually backed by any USDs or other asset.

Here I cover what Stahl and Bregman et al at FRMO/HK have said on these topics as well as some notes from other POVs on the subject2.

“1. Identify the possible hypotheses to be considered. Use a group of analysts with different perspectives to brainstorm the possibilities. 2. Make a list of significant evidence and arguments for and against each hypothesis.” — Psychology of Intelligence Analysis (Step-by-Step Outline of Analysis of Competing Hypotheses)

Structural commodity shortage

Notice, in the YTD heat map above, how — aside from healthcare — the corner of energy, utilities, and basic materials shines the brightest out of all other sectors in the S&P 500.

Commodities have been one of the only sectors going up in a time where tech and other crowded, once-reliable names/sectors for set-and-forget performance have been humbling many investors, both retail and institutional. Meanwhile, FRMO has been sticking to their long-energy stance since before the 2020 lockdowns and correctly (as events have unfolded so far) called the non-transitory inflation situation we are in today right in the early months of the lockdowns — though you wouldn’t be able to tell from their TBV as any gains in their energy bets have been getting counter-balanced by the recent crash in the price of Bitcoin at the same time via FRMO’s significant $GBTC holding (which I may go into when covering the BTC-related points on another post). Given that ~40% of FRMO’s TBV is in the oil royalty stock $TPL — as well as even more of their “portfolio” bps in other smaller energy and commodities businesses — the long term success of this corner of the map (maybe, sans utilities) is a critical bet for FRMO.

(Of course, Stahl has arguably been wrong before —here, underestimating the rise of tech stocks that would continue for decades after the popping of the 2000 dot-com bubble.)

One last thing I’d like to mention before continuing on here is that, when it comes to these commodity / macroeconomic predictions, I am reminded of this Warren Buffet video…

… and this quote from Seth Klarman’s “Margin Of Safety”:

“By way of example, a top-down investor must be correct on the big picture (e.g., are we entering an unprecedented era of world peace and stability?), correct in drawing conclusions from that (e.g., is German reunification bullish or bearish for German interest rates and the value of the deutsche mark), correct in applying those conclusions to attractive areas of investment (e.g., buy German bonds, buy the stocks of U.S. companies with multinational presence), correct in the specific securities purchased (e.g., buy the ten-year German government bond, buy Coca-Cola), and, finally, be early in buying these securities. The top-down investor thus faces the daunting task of predicting the unpredictable more accurately and faster than thousands of other bright people, all of them trying to do the same thing.” —- Seth Klarman

HK/FRMO

Question: why might the oil price spike much higher with the world focusing on going green? I don’t believe it will ever happen that oil drilling will be done away with completely. Yes, President Biden can stop drilling and fracking on government properties onand off-shore. That will reduce supply, not demand. Demand will continue for 6,000 products made from petroleum (link). —- Lawrence Goldstein, Santa Monica Partners LP, Director at FRMO (https://irp.cdn-website.com/cfd0d660/files/uploaded/SMP%20Q1%202021%20Letter%20to%20Partners.pdf)

The basic idea that Murray Stahl is putting forward here on inflation is that…

We’ve had a 40yr depression of commod prices starting from the 1980s due to a series of significant one-time events or trends that allowed the developed world to “export inflation” around the globe that are now reaching their limits as globalization and other long-running trends begin to break down ⇒ underinvestment in commod industries about to be felt by the world as all the players who’ve been “leveraged” on cheap commod availability are about to face their own “credit shock”. Starting around the 1980s, we’ve had…

Growing world population ⇒ growing demand3

Liberalization and collapse of the USSR starting in 19874 == a onetime event that brought a lot of commod supply online to global markets by allowing Western companies / commodity traders (who had access to global physical and capital markets) to come in and take managerial control of commodity production and distribution which was formerly the role of the now-dissolved centralized soviet state5. This uptrend in commodity supply appears to be now plateauing and may move into decline in the medium-term.

Chinese economic opening in 19786 == a one-time event that brought a lot of low-wage labor supply online to global markets (which is reaching capacity in both physical and political terms) — that also spawned copy-cats like India, Vietnam, etc.

********** UPDATE 20230914: Not only is this capacity of cheap labor reaching a physical limit, but China is also inching towards a more insular state of being and stimulating domestic consumption, which will affect its degree of exports to the rest of the world —pursuing controlled decoupling over past goals of overtaking the USA as the worlds largest economy.

On exports, Xi said that China needs to stabilize exports to developed countries and expand exports to emerging markets. Compared to consumption and investment, however, exports clearly are not considered a main driver for China’s 2023 growth in Xi’s article, given rapidly slowing external demand and the decline of export growth in late 2022. —- http://www.international-economy.com/TIE_W23_Malmgren.pdf

**********

A 25pps decline in corporate tax rates from the ~45% of the 1980s, which can’t be duplicated again with corp tax rates now sitting at around 21% —unless the Overton Window is open for near-0% corporate tax rate (which seems unlikely).

A 90% decline in interest rates from an FFR of ~15% to ~2% (that, again, certainly can’t be done again given that nominal rates are now in the low single digits)

(Relatively more recent) policy of ESG capital allocation across the Western financial system ⇒ reduced available capital for critical (“legacy“) commod investment — or at least raising the cost of capital for such investment/financing

And now RU-UA war and sanctions ⇒ taking both RU and UA commod supplies offline — at least to a partial extent when it comes to UA. This conflict has added time (and thus costs) to the global supply chains.

So basically, they are thinking: either inflation or stagflation and that whether we have a recession or not, the cost of opex/capex commods are going to keep going up because of the underlying, long-term factors stated above that have reached either physical or political limits7.

So far as I can tell, HK has been on this thesis since around 20188.

********** UPDATE 20230117: Some questions on this: The oil price run-ups of 2000, 2008, and 2014 were followed by declines equal to exceeding 50%. Could management give some of their thoughts on why this time is different? As a supplementary question, I have read previous HK Commentaries where the idea that there are commodity supply trends that are now dying out is used to support a "structural shortage" thesis beyond the more current capex narratives, they are: The liberalization and collapse of the USSR that enabled western companies to bring in the global capital and physical markets and the opening up of China that brought a lot of cheap labor into the global marketplace (a model which was then copied by many other countries). How does management quantify the impact and, ostensibly, the decline of these trends in any approximate sense of direction and magnitude? **********

********** UPDATE 20230817: FRMO co-chairman Steve Bregman referred to this thesis as the ‘end of the 40-year global labor & manufacturing arbitrage’ and explains this idea in a bit more detail in an HK commentary published a few weeks after this post was originally published in a section titled “The End of the Exporting-Inflation Era”, here: https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q2-2022-Review_FINAL_2.pdf

Bregman contends that economists have been overly focused/relying on the Philips Curve (correlating lower unemployment to higher inflation) (the uselessness of this curve has been addressed in a Fed article here), success of the Federal Reserves’ management of inflation expectations by the market, technological progress and associated labor synergies, and the supposed correlation between aging population and lower inflation among nations.

On the other side, Bregman argues that what should be of more focus is the acceleration or, more specifically, deceleration of:

Russian oil production (eg. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Russian-conventional-oil-production-based-on-a-compilation-of-historical-sources-for_fig2_262188782; video),

export numbers from low-wage nations like China and India (eg. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/chinas-economy-40-years-of-soaring-exports/) and their population growth rates,

the bottleneck of global port capacity growth (eg. https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter5/intermodal-transportation-containerization/world-container-throughput/),

and the USA’s fracking production.

**********

Some quotes and notes from various HK and FRMO publications are below:

HK Commentary 2Q2021

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q2-CVALUE-Review_FINAL.pdf

Critical Commodities Supply vs. Transitory Inflation

[...]

The problem is that on the supply side, production for many of these commodities is not increasing. For many of them, that’s related to cyclical price collapses of nearly a decade ago, and the consequent decision by producers to reduce spending and not develop new reserves. That disinvestment process has been happening for many years. Likewise, many years would be required to reverse that trend, even under ordinary circumstances. [...] But supply is subject to a recent add-on constraint, and that is political and regulatory pressure on the extractive industries to not increase their carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions.

If you read this article further, they then go down the line of various commods and show declining capex investment spending across all industries for baskets of representative companies w/in each.

I think this is a good summary of Stahl and co’s thesis on the coming inflationary cycle their betting so heavily on – basically the idea that a lot of LT deflationary trends starting in the 80s are now reaching their limits:

HK Commentary 4Q2021

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q4-2021-Quarterly-Review_FINAL.pdf

Know a Change of Era When You See One

[...] The near continuous, 40-year decline in interest rates, from 14% in Jan 1981 to 1.7% now.

[...] The 40-year increase in stock valuations, from 0.5x GNP in 1981 to 2.7x now.

[...] 40 years of exporting inflation

[...] Not to give short shrift to 40 years of reduced corporate tax rates…

[...] And 40 years of falling commodity costs

[...] Plus, the more recent decade-long decline [starting w/ the 2014 oil bust] in other commodity prices.

[...] And 40 years of technology-driven corporate efficiencies

[...] Leading, ipso facto, to 30 years of rising corporate profit margins.

[...] That picture of what seems to be the intrinsic character of the U.S. economy and markets – moderate to low inflation, moderate to low interest rates, and rapidly rising earnings, albeit temporarily punctuated by the odd tech or real estate bubble – is pretty much all that a 45- year-old has ever personally known. Experientially, it is entirely normal and ordinary. But only within that time frame. A time frame demarcated by a unique confluence of discrete, powerful systemic trends that have run their course, not to be repeated:

• A 40-year, 90% decline in interest rates. They can only go from 14% to 1%, once. • 40 years of exporting of inflation – labor and manufacturing costs – through the opening of previously closed developing-nation markets. Not only can’t that be repeated, many of those nations have evolved technologically and are now competitors. • A 40-year, 25%-point decline in the corporate tax rate. With today’s 21%, that certainly can’t be repeated, unless the tax rate becomes a negative figure. • A 40-year trend of declining commodity costs, including: o A 45% decline in the price of oil o The opening of the Russian/formerly Soviet hard commodity supply market o A decade-long decline in a broad swath of essential other commodities. • The 40-year incalculable corporate cost/benefit impact of the appearance and ascendance of both the personal computer operating system and the internet. • A 30-year trend of rising corporate margins, to levels never before seen. • An all-time historic high stock market valuation, via the simplest, most direct calculation: the total value of the stock market as a % of GDP.

(Ie. Volcker’s rate hikes of the late 1970s had much contributing impact on ‘breaking the back‘ of inflation).

When Stahl talks about structural shortages, these long term trends and their now-fading effects are what he’s referring to. Though in the 1Q2022 HK Commentary, Stahl does also allude to the idea that there is just not enough commod supply for non-discretionary demand.

HK Commentary 1Q2022

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q1-2022-Roundtable-Discussion-for-Website_FINAL.pdf

Do you think that extremely high commodity prices will cause a recession? What is the outlook for commodity prices in a recession?

[...]

[E]ven if people aren’t buying as many cars — but there’s less steel and iron ore capacity than is necessary, you’ve got a supply deficit anyway. With oil, which we’ve been talking about, it doesn’t matter if there’s a recession. There’s a basic shortage of necessary commodities relative to demand. That’s very different.

Though to this, I’d say that the Fed could just kill demand in a recession — or better put, if there were a recession, demand for opex/capex commods would not be the same as it is right now. Would current supply be enough for such new levels of lowered demand?

On the other hand, would supply shrink in a proportional fashion to demand in a recession as producers go BK or invest even less in production capex — as happened during the 2020 lockdowns? Ie. If there were demand destruction from high prices, would there also be supply destruction canceling out it’s LT deflationary effects?

In this commentary, Stahl/Bregman lay out the structural commodity shortage like so…

[...] Well, to begin with, as far as the economic cycle goes, commodities have been in a recession/depression for 40 or 41 years, other than the occasional few months of exceptions to that. Not a recession, but a depression.

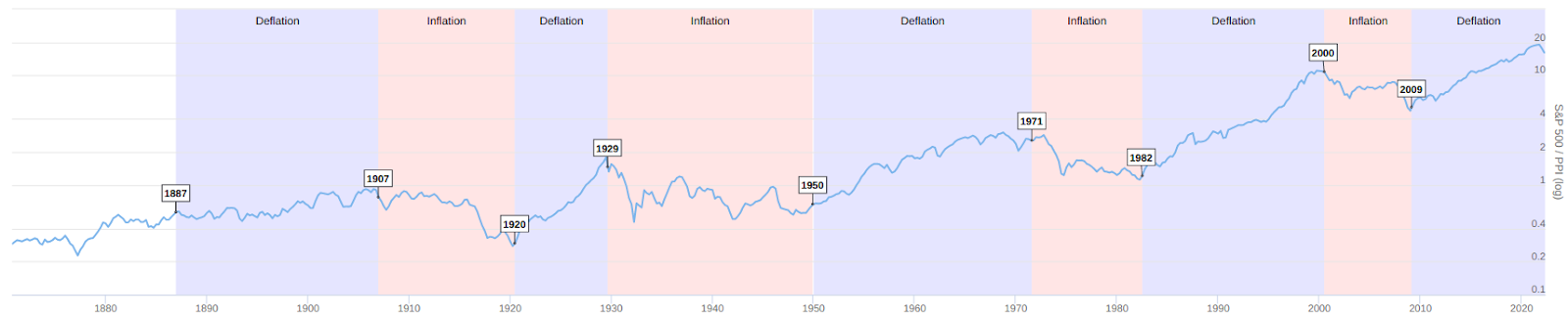

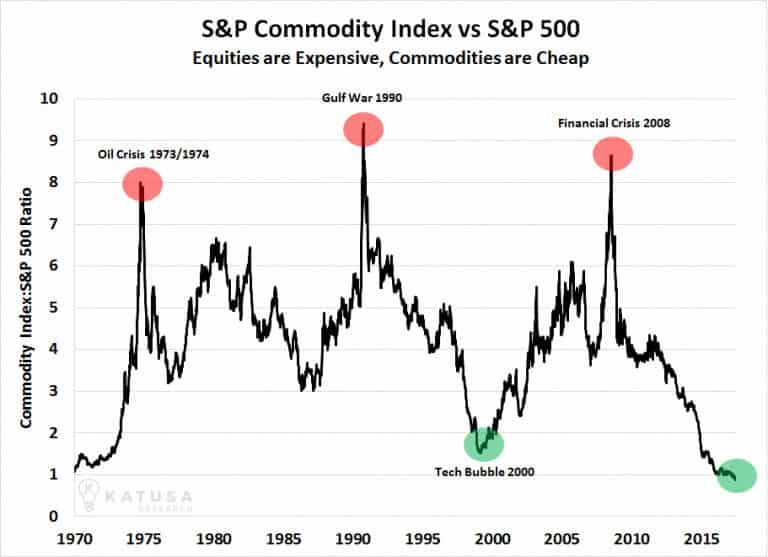

Looking at a the S&P 500 vs PPI commodity gains for the past ~150 years, we see that the S&P started breaking away from commod returns starting in the 1980s as interest rates were brought lower taking the ratio into the 15x range from the mean 1-2x range — kicking off a relative depression in commod returns for the 40 years after (and possibly setting commodities up for a massive bull run if this mean were to revert — and/or setting up the S&P 500 for a massive crash).

…Though I wonder if this declining return of commods vs general stock market is maybe reasonable?

Aside from the 40yr trends that are mentioned in the 4Q2021 HK Commentary, here they also go one to cover…

[...] Number two, there are a lot more people in the world. Demand actually increased.

[...] Even before the [USSR] empire legally collapsed, it was in the process of collapse, and to obtain hard currency, they would dump their commodities on the market, be it oil, or copper, or gold, or diamonds, or what have you. So, that held commodity prices down. And today, we’re in a very, very different position than we were for the last four decades.

[...] As if this depression in commodity prices, the competition from the collapsed communist states, the withdrawal of asset allocation capital from these industries, wasn’t bad enough, there’s been the impact of the ESG movement for the last five or six years at least.

[...] Then along comes the Russia-Ukraine situation. A couple of things about that, particularly about the sanctions. [...] they’re autarkic, in the sense that they don’t really import anything they need; they just import things that they want. [...] Russia accounts for about 35 percent of global nitrogen-based fertilizer production.

So we have…

A 40yr depression of commod prices due to a series of significant one-time events or trends now reaching their limits ⇒ underinvestment in commod industries about to be felt by the world

Growing world population ⇒ growing demand

Collapse of USSR == a onetime event that brought a lot of commod supply online to global markets by allowing Western companies / commodity traders to come in and take managerial control of commodity production and distribution which was formerly the role of the now-dissolved centralized soviet state (which is coming to a close)

Chinese economic opening == a one-time event that brought a lot of labor supply online to global markets (which is reaching capacity in both physical and political terms)

(Relatively more recent) policy of ESG capital allocation across the Western financial system ⇒ reduced available capital for critical (“legacy“) commod investment — or at least raising the cost of capital for such investment/financing

And now RU-UA war and sanctions ⇒ taking both RU and UA commod supplies offline — at least to a partial extent when it comes to UA (and I doubt RU is going to be very accommodative of the world re their commods if/when the market reopens to them (as they kinda already have everything they need internally)) — and certainly added time (and thus costs) to the associated supply chains

[...] So, whether we have a recession or not, I think we’re going to have inflation; this is just one more inflationary factor. And we might have a recession just because of the inflationary shock. It’s possible. So, commodities are in very, very good stead and that’s just the way it is right now.

So basically, they are thinking: either inflation or stagflation and that whether we have a recession or not, the cost of opex/capex commods are going to keep going up because of the underlying, long term factors stated above.

I think the way I’d be more comfortable w/ this idea is to see some metric of how much demand is non-discretionary — ie. how much would be left in a recession and how that compares to how supply would look in a recession.

HK Commentary Interm 1/2Q2022

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Interim-Q1-Q2-Commentary-2022-with-TPL-addendum_FINAL.pdf

I also just thought this analogy framing USD printing vs commod production like a FX exchange rate input was an interesting POV:

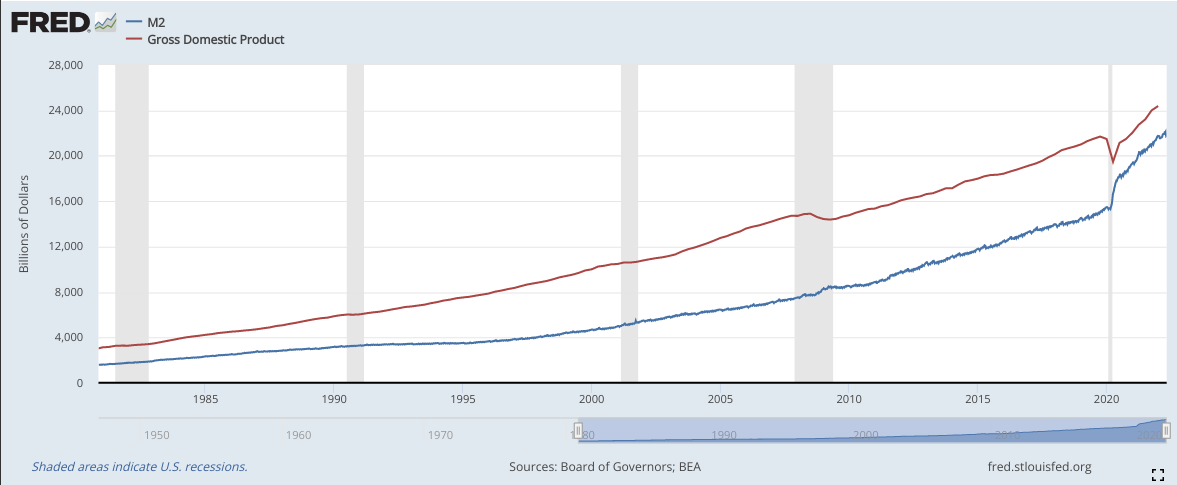

If the supply of oil were to grow even as high as 2% a year, while the supply of currency to pay for it is growing at 12% a year, then the price of oil measured in currency is going to go up. The discussions around inflation and currency debasement would be easier to understand if people said, or could see, that it’s really like a currency exchange rate, except oil versus currency instead of once currency vs. another. The fiat currencies are going to fall in relation to a barrel of oil: much more currency supply circulating every year for each available barrel of oil; more dollars or Euros or yen, but not much more oil.

FRMO CC 1Q2022

This simple idea of money supply growing faster that “stuff supply” as the main cause of inflation is also mirrored in the 1Q2022 FRMO CC:

The principal basically is, there's a supply of goods and services in the growing economy that increases. And that could be oil, it can be cheese, it could be cars, it could be whatever product you want. So, all these different products and services. The amount of money in the system is growing faster than the products and services you could buy with that money in the vast infinite variety, almost infinite variety of the products and services you will buy. What's going to happen? If you believe in the law of supply and demand as I do, that the money will buy less products and services, because that flows by demand.

[...]

So all the things you can buy, I don't think anybody would assert that the things you can buy, whatever it is that you like to buy is growing at 10% a year [the M2 money supply growth rate]9. That's debasement.

Essentially, Stahl is describing the end of a long-running global commod and labor deflationary arbitrage from the collapse of the USSR and opening up of China, respectively. These are structural issues that (in addition to the most recent capex lulls and ESG barriers, post-2014 oil crash) would not necessarily be solved by any opex-inflation-led demand destruction. Stahl argues that inflation (CPI + M2 growth) over the last 40yrs since 1980 have been counteracted by the commod and labor arbitrage described above.

Other public oil bulls

Here we can see some of the POVs that are also long energy (or otherwise warning of commodity shortages). There are many other sources with this perspective, but think the general idea can actually pretty well conveyed by just a few names that we can cover here.

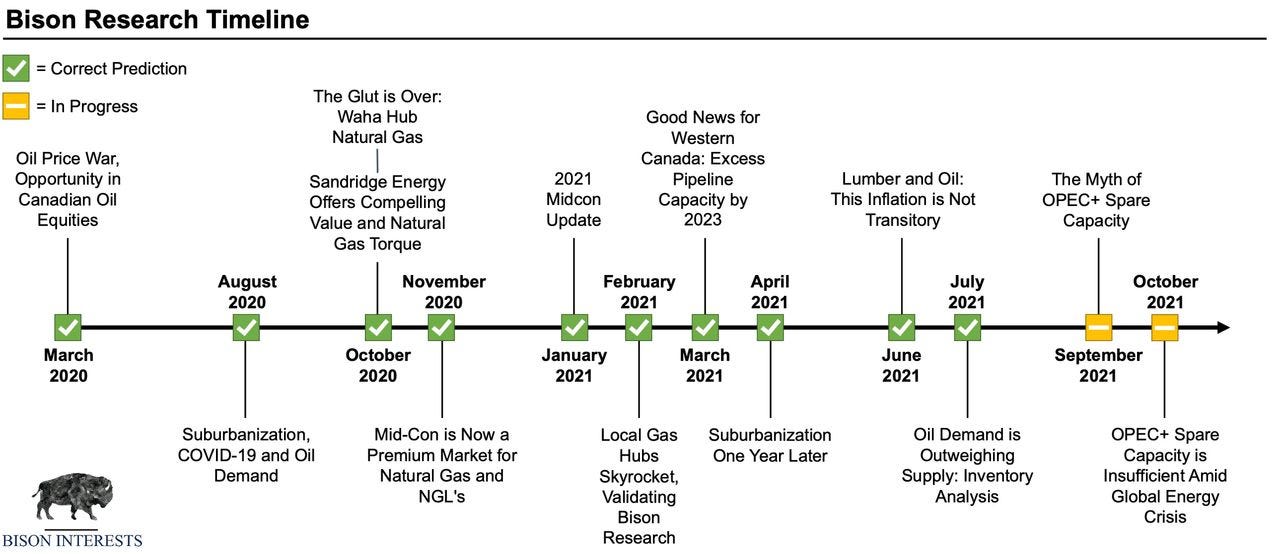

Bison Interests / Josh Young

On FinTwit and many other places, Bison Interests’ CIO Josh Young has been on the long-oil train for a long while and since I’ve been following his writings — since around mid 2020 — his track record of predictions has been pretty good. You can find his writings here: https://bisoninterests.com/content

…but this video is a good quick overview of his POV on the oil situation in late February (TLDR: Basically has to do w/ the traumatized behavior of O&G shareholders and management, post-2014 oil bust, as well as fossil-fuel-hostile ESG investing and gov policies that has only been exacerbated respectively by the 2020 O&G bankruptcies and vociferous/litigious climate-change/anti-fossil-fuel activists leading to overall declining inventory and CAPEX reinvestment, while demand continues to rise over time):

A longer one here:

Doomberg

Doomberg started in early 2021, transitioning/adding a substack subscription service to their industrial consulting business, when many businesses had to pull forward their digital transition plans (or start making and executing on them at all) in response to the lockdowns and I’ve found mostly all of their articles to be very interesting. According to Doomberg, high prices taking care of high prices – via increased supply by the industry to capture those excess profits – is not as much of a certainty given the restrictive and fanatical western policies in place and that continue to be pushed to support ESG, green energy transition goals. I would not, however, rule out high prices taking care of high prices in terms of demand destruction and possible recession.

There are at least four forces aligning as huge tailwinds for fossil fuel prices. First, and most important, the ESG/progressive crowd has utterly and totally won the narrative war and they will press the consequence of their undeniable victory to the maximum by attacking supply at every opportunity. Second, the fossil fuel industry is coming off a period of extended underinvestment in capital projects already, which was exacerbated by the fallout from the COVID-19 crisis. Third, massive monetary and fiscal stimulus is stoking demand for commodities globally, and fossil fuels will not be exempt (on the contrary, since fossil fuels are critical to the production of other commodities, they will feel an amplified effect of this phenomenon). Finally, and related to the third force, fiat currencies are being debased at an unprecedented rate.

In a world where US oil production tapers off, spare OPEC+ pumping capacity fails to materialize, financing for new exploration and development continues to shrink, and demand for oil in the West continues to grow while exploding higher in the emerging economies, what happens to price?

“And so, I hope President Putin will help us to stay on track with respect to what we need to do for the climate.” – John Kerry, February 23, 2022

In the pantheon of unserious statements by a leading US official on the literal eve of war, it will be tough to top the one quoted above from former Secretary of State and current Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry. Kerry’s sober concern for the emissions that will result from Putin’s aggression is only topped by his worry that kinetic war will distract attention away from the climate crisis.

Is there any doubt how we got here?

Goldman Sachs

(Note that while FRMO management take no fees or salary at all and small funds and analysis outlets like Josh Young and Doomberg are risking their individual online reputations, big institutional oil bulls like GS and Citi are the ultimate fee takers and — as 2008 has shown — have no longterm reputational risk from ever being exposed for fraud/manipulation let alone simply being very wrong; that is, in the long run, they have the very least to lose of the groups described. Something to keep in mind in particular when looking at multi-billion dollar asset management companies hyping the oil shortage thesis). More on this in a later section.

UPDATE 20210117: Because of the reasons above, I’ve decided to just “remove” GS and Citi’s opinions from this. The strike-through formatting here still leaves the text legible to get the details of their marketing, but IMO it’s enough to know that —earnestly or not— they are hyping the oil bull thesis.

This is a set of slides from GS in March 2022 outlining their case for the energy sector, specifically midstream in this case. (Note that I recall that GS has been bullish on oil for a long while, so it’s not like the production of this slide deck in itself is some kind of sentiment indicator of any kind of inflection; just including here for as it does sum up the general consensus long opinion):

Citigroup

Before writing this post, I also had some articles saved from Citigroup, who in February were — at least publicly10 — short oil, calling for oil to fall to ~$65/bbl.

To Citi’s Morse, however, the undersupply is a temporary affair brought about by seasonal factors. “We see the near-term tightness as a winter phenomenon, and see global oil balances moving back to surplus in the second quarter,” he said as quoted by Bloomberg earlier this month. ——https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/The-Lone-Bear-Calling-For-65-Oil.html

In Morse’s view, this supply imbalance would be rectified by US supply — which I find a bit unbelievable given the current Dem-run Congress + White House admin’s disdain for fossil fuel production11 and emboldened ESG activism on the private side in the US:

Citi’s Morse is placing a specific focus on non-OPEC supply and specifically U.S. supply. Despite drillers’ continued financial discipline, Morse expects that U.S. crude oil production this year will rise by at least 800,000 bpd and further by more than a million barrels daily in 2023. That would bring it to a record of 13.9 million bpd, Barron’s notes in the interview with the Citi commodity expert.

However, they have since backed out of this stance due to what they claim is increased uncertainty in the oil supply markets caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

“While our market outlook remains out-of-consensus and we continue to project significant downside for crude oil prices in a six-to-nine-month context, the timing of this was negatively impacted from the escalating Russia-Ukraine conflict, widening supply risk premiums, and upward price momentum for the crude oil futures strip.” ——https://www.barrons.com/articles/prominent-oil-bear-throws-in-the-towel-others-are-ramping-up-short-bets-51646247617

I find the blame on the RU-UA war a little odd given that Brent oil prices did not seem to have any problems moving up in the YTD up to the week preceding Russia’s attack (rising ~22% from Jan 1 2022 to Feb 14 202212).

Another interesting thing about this statement from Citigroup is that they claim that their bearish oil stance is out-of-consensus, yet the same article goes on to mention that “Energy is the third-most shorted sector of the economy, after consumer discretionary and healthcare“13

UPDATE 20230120: Anas Alhajji is another intelligent supporter of the ‘looming energy crisis’ theory and his 2023 outlook has had the paywall removed and can be read here:

On a related note, Alhajji is also a supporter of the coming natural gas arbitrage theory between US and RoW’s LNG prices as the massive imports of Canadian, Mexican, and US domestic LNG being getting arbitraged out to the global markets as more export capacity is built in the US to reach those physical markets, while the most productive domestic existing NG plays begin reaching production plateaus. This idea is also articulated in the a Goehring & Rozencwajg letter here.

Deflationistas (and The Dallas Fed)

Reading around, I think the general Deflationista POV can be heard by Alhambra Investments’ Jeff Snider re. the causes of inflation (BTW, this YouTube channel is just interesting in general — if not a bit repetitive, recently):

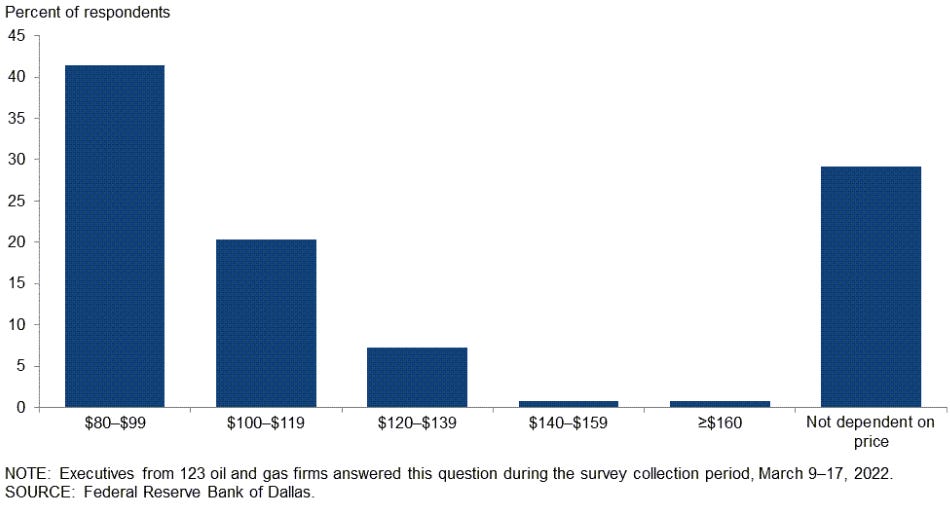

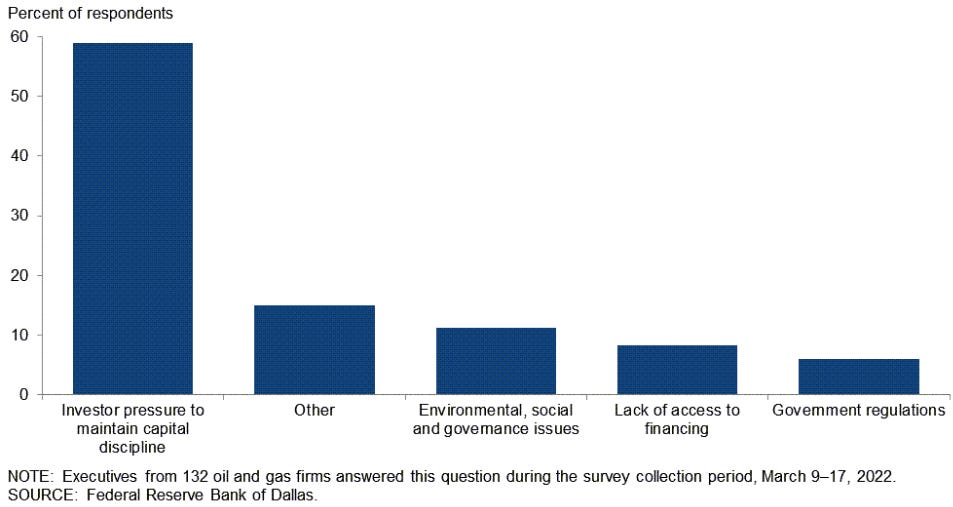

(and here) – which can be summed up in the following Dallas Fed survey results from Texas oil producers…

By what percent do you expect your firm’s crude oil production to change from fourth quarter 2021 to fourth quarter 2022?

What West Texas Intermediate crude oil price is necessary to get publicly traded U.S. producers back into growth mode?

Which of the following is the primary reason that publicly traded oil producers are restraining growth despite high oil prices?

==> bond/shareholders are warning management not to chase oil prices — they don’t trust the currently high oil prices to remain stable long enough to reward the time and capex VAR involved in making these production investments. Of course Snider et al (sticking with the “the bond market is always right and with it’s persistently low yields is predicting a recession” thesis) says this is due to bondholders (exclusively) saying that they don’t think things are going to end well for oil — or the economy in general — and so don’t want these companies wasting capital on increasing production investments. That is, higher prices are going to take care of themselves in due time — in the form of demand destruction14.

IMO, this is Snider looking at data that could accommodate his theory and then making the leap that it thus indicates exactly that, whereas I think it’s not necessarily true that the “investors” oil execs are talking about here are the bondholders nor is it obvious what the investors in question are concerned about here — they could very well be concerned about not repeating the capex / supply glut that crashed the oil market in 2014 or concerned with one of the other available categories in the survey (and execs are just citing investors b/c they agree with them (I guess it kinda depends on exactly what the wording of survey they filled out was)).

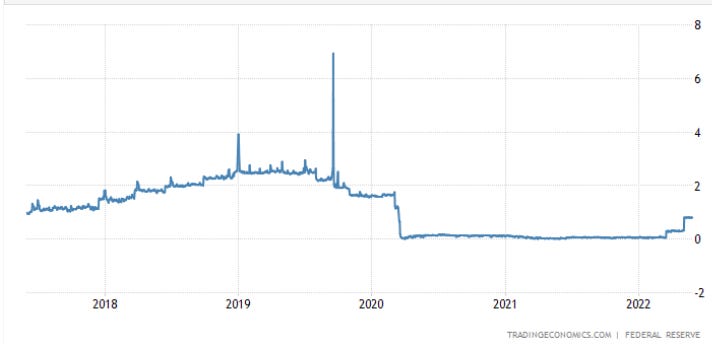

Though one thing I will say is that if we’re getting back to a normalized pre-2020 economy, it should be noted that there was a significant repo rate spike in 2019 — which typically indicates liquidity problems in financial markets15 — which was accompanied by talks of an economic slowdown (which may have been scapegoated / obfuscated / simply pushed back by the 2020 lockdowns and crash).

Bison Interests’ Josh Young actually had some things to say about this Fed survey — and this question about capex investment restraint in particular — in a recent interview: https://macrohive.com/podcast-transcript/podcast-transcript-josh-young-on-200-oil-and-the-structural-energy-supply-problem/

There was even a Dallas fed survey where they published something. I think they were very careful about the questions they asked. As an economist, you get trained in ignoring surveys and observing behavior. You want to care about purchase behavior and not what people say. And one of the problems with looking at what people say, especially in responses to surveys is that you can construct a survey with certain questions and you can literally get the opposite result depending on how you structure the questions. And people won the Nobel Prize in Economics for this. A lot of behavioral economics, they observe kind of, if you frame something one way versus framing it the other way you get opposite results.

OK Josh, but what if you're the one who’s wrong? Have you seen the exact wording for this poll question? (I haven’t, I’d like to). I also doubt Young’s Twitter spaces interview has the same sample size as the Fed survey here.

Many people have been citing this Dallas fed survey, which again, from what I can tell is totally wrong. It was just misrepresentative and many people will show this chart and say, “Oh, well on the left side of the chart, there’s the big bar that says that it’s people saying they want to return cash to shareholders. And the small bar is that they’re worried about policy.” The reality is that they’re all worried about policy. And that it’s really hard because even if you weren’t worried about policy, which they are, every executive that I’ve talked to is concerned about additional negative policy, which is real. The regulators are ramping up. Like the SEC is now increasing their disclosure requirements, which may then be used, that information may be used to pursue these companies in court and tax them more and other stuff.

TBH, he’s basically just claiming this here — he’s just going “The Fed survey is wrong, here’s what oil producers really care about…” w/out really going into much detail about why it’s OK to just dismiss the Fed survey off hand like this. I would however be open to the idea of some survivorship bias being represented in that survey — ie. that there may have been many other O&G firms complaining about the various other factors pre-2020, but where wiped out in the wave of O&G bankruptcies when oil demand dropped during the lockdowns, so are no longer around to voice their complaints. Unfortunately, the Dallas Fed energy survey archives only goes back to 1Q2020 and this specific question does not appear to be asked in the older surveys.

IMO, this “bond market is signaling major global liquidity problems” take — even if true and does end up proving correct in the form of a recession — does not really damage the ability of oil equities investors to recoup their investment (and the opportunity to buy the dip) and make a respectable CAGR in the long run as it does not really affect the idea that production bottlenecks are real/durable and shortages truly structural (ie. it does not negate the necessity of massive new capex investment into the O&G industry in the long run). We could very well have a recession directly caused by high energy (and food/fertilizer) prices, but this may not be enough to bring these commod prices down16 for any extended period…unlike the next POV.

The World For Sale (and subsequent storage and rehypothecation)

One other thing that I can’t get out of my mind is the theory hypothesis proposed by Ektrit (Kris) Manushi that all of the commod shortages we are seeing/hearing about is a manufactured crisis (accompanied by narrative propaganda) that could be solved much faster than any of the aforementioned oil bulls thinks possible — certainly a scary tail risk.

The idea goes thusly:

https://economics-is-a-dogmatic-religion.blogspot.com/2021/11/how-oil-market-works.html17

Basically, oil is sold or presold (by rulers/oligarchs in commod-rich countries like Russia, China, and the middle east) to global commod traders (eg. Glencore, Vitol, etc) that store that oil around the world and use it as collateral for rehypothecation in the UK — where unlike in the post-2008 US, there are no limits on rehypothecation — for funding other trades.

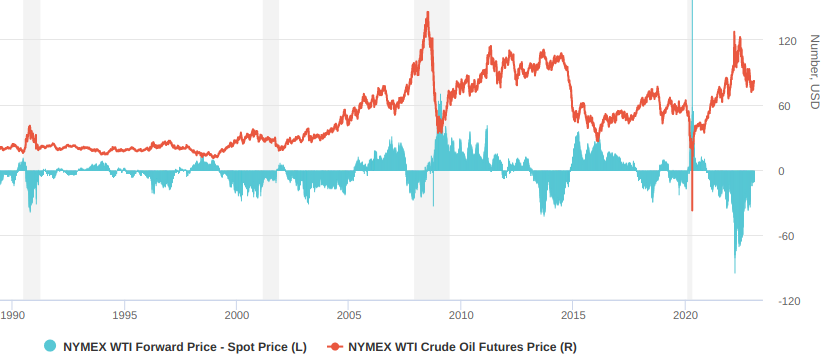

These vast quantities of hidden barrels could end up being dumped into the supply market for final sale — and disincentivize this kind of leveraging into the future — if their margin rates rise with the Fed Funds Rate and trigger margin calls resulting in these traders having to firesale their oil collateral. In this way — supposedly — the Fed can “print“ oil in a sense. Thus, the commod shortage is not structural and heightened rates would crash oil prices, allow the IEA to suddenly “find” more barrels, stop OPEC+ from “missing” their quotas, and thus allow oil equities to remain suppressed for the long term. (This may be good for the world in the long run, but would certainly be a killer for any oil investors18). Look to this happening before the 2022 midterms.

I normally would not really think much of this, since it’s just a theory that I don’t really see any actual data or historical precedent for — and Ektrit’s apparent total certainty in himself is grounds enough for highlighted skepticism towards the claims. Furthermore, it’s not really even something that can actually be diagnosed (ie. have any set of fact-patterns or evidence directly causally linked to that hypothesis in particular vs any other competing one) — short of some big whistle-blower story given that it’s all about this person’s insider knowledge/rumors of hidden inventories being secretly rehypothecated and any data you see from oil execs or the IEA is apparently just convenient propaganda19 to either attempt to manage market expectations or cover for mega banks and commodity trading houses; an unverifiable spaghetti-monster-in-the-sky category of hypothesis where anything that happens can simply be claimed to have some covert link back to this hidden rehypothecation dynamic. However, I did read Javier Blas’ “The World For Sale” as well as “The Asylum: The Renegades Who Hijacked the World's Oil Market” and so have a hard time simply dismissing this idea outright — especially given the significant tail risk to any long oil investment it represents. It’s not like there isn’t a precedent for commodity manipulation at a global scale.

(I will note that this theory seems to imply the doubtful view, IMO, that the Fed et al do not see any problem with the second-order effects of (even greater) “capital discipline” as the Dallas Fed survey describes it and subsequently greater lack of / disinterest in O&G capex investment (eg. in E&P projects) for expanding, let alone maintaining existing, oil production rates that would come from another bust in oil, similar to the reaction to the 2014 shale bust).

You can listen to Blas cover this topic more in the interview here (I’ll note that, while he mentions the leveraged nature of the commod trading operations, he never seems to mention anything suggesting that these trading houses are hoarding commods for rehypothecation):

********** UPDATE 20230116: There is also credence to Ektrit's hypothesis from past looks at the dark inventories of commodities and manipulation of financialized commodities markets --similar to the manipulation seen in the 1996 Sumioto Affair and the 1985 Tin Crisis which involved market manipulation over multiple years-- here below.

This is highly speculative and I don't really know much about the futures market, but my understanding of the idea here is that global commodity traders are using oil as collateral for derivatives (financial contracts that derive their value from the performance of an underlying asset, here oil). The oil inventory is prepaid20 for or leased from global producers like Aramco and Exxon (who are structurally short oil) --by simply transferring a title of ownership from the producers to the financiers, while the oil itself does not move from underground or its storage tank-- and used as collateral, meaning it is put up as security to guarantee the performance of the derivative contract. Really most oil producers as I understand it --certainly shale producers in the US-- need to hedge their forward production prices in order plan and get financing to invest in that future production, so they're happy to have someone come along and make the market for their hedges in the form of long-dated futures contracts. Rehypothecation allows for the using of the same collateral for backing multiple derivatives contracts, which is a common practice in the London, UK financial market —and unlike in the US, the UK has no limits on how much leverage can be created this way21.

This allows for the collateral to be reused and increase the amount of derivatives that can be traded by creating "collateral chains" where the same collateral is used many times22. These contracts would rarely actually ever be required to settle in physical delivery of the underlying asset23 --a good amount don't even have delivery as an option in the contract24-- as they are mostly used for hedging and speculating purposes25. A major source of demand for these futures comes from commodity-based investable index funds such as USO or Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (S&P GSCI) and various funds linked to that index (which are structurally long oil) who need to continually roll the various futures contracts they are composed of.

Now you see where an arbitrage comes in so long as inflation remains a fear for HF and retail investors who will seek to move capital into 'inflation hedged' products. Iff this is the case, you can see how higher --sustained-- rates (above some (nudgingly manipulated) CPI number) can starve capital from the long end of this arbitrage (as investors get a riskless inflation-beating yield via their savings accounts and USTs), margin call / unwind the rehypothicated collateral chains, and impel the financiers to end their leases and release their 'dark inventory' onto the global markets of the real economy --the Fed could indeed print oil in a sense (and are perhaps even along side the manipulators, which would be an even worse prospect for oil longs26). Furthermore, my understanding is that margin requirements for the collateral backing commodity futures contracts are in the mid single digit to low double digit percentages —meaning even more leverage can be applied by using the same lot of collateral to back multiple contracts.

My one lingering question is why again and/or now? The only thing I can think of at the moment is that COVID and the supply-chain congestion and ensuing inflation were used as an excuse for the global players of the Brent Oil Complex to run the arb... again, highly speculative and I am not a finance person. Also, the Brent (and WTI) futures curves have been in backwardation since around early 202127, so how can pre-paying or leasing producer inventory for creating futures contracts still be profitable (for both E&Ps and financiers)? In backwardation the producers have less incentive to hold inventory into the future or to invest in production capex for future extraction and financiers would be selling futures in an environment where they would need to end up paying out at the higher spot price to whoever bought the contracts --I suppose producers could still be happy from just the elevated price, while in a similar manner financiers could still profit by selling futures to massive commodity index funds, ETFs, et al at the front-end as they roll their contracts from month to month, while using relatively little capital to support the illiquid back-end of the curve.

**********

Summary

So just to summarize the current POVs I’m looking at one more time, we have:

FRMO’s “end of a 40yr commod depression“ thesis (accompanied in some ways by other oil bulls), wherein we’re seeing the end of…

• A 40-year, 90% decline in interest rates. They can only go from 14% to 1%, once. • 40 years of exporting of inflation – labor and manufacturing costs – through the opening of previously closed developing-nation markets. Not only can’t that be repeated, many of those nations have evolved technologically and are now competitors. • A 40-year, 25%-point decline in the corporate tax rate. With today’s 21%, that certainly can’t be repeated, unless the tax rate becomes a negative figure. • A 40-year trend of declining commodity costs, including: o A 45% decline in the price of oil o The opening of the Russian/formerly Soviet hard commodity supply market o A decade-long decline in a broad swath of essential other commodities. • The 40-year incalculable corporate cost/benefit impact of the appearance and ascendance of both the personal computer operating system and the internet. • A 30-year trend of rising corporate margins, to levels never before seen. • An all-time historic high stock market valuation, via the simplest, most direct calculation: the total value of the stock market as a % of GDP. As well as... - Growing world population ⇒ growing energy demand (especially as EMs begin developing their economies to the next stages) - Relatively recent policy of ESG capital allocation ⇒ reduced available capital for commod investment — or at least raising the cost of capital for investment/financing - RU-UA war and sanctions ⇒ taking both RU and UA commod supplies offline — at least to a partial extent when it comes to UA (and I doubt RU is going to be very accommodative of the world re their commods if/when the market reopens to them (as they kinda already have everything they need internally)) Exacerbated / pulled forward by... - The 2014 oil bust traumatizing oil investors/management into a more defensive capital allocation stance (or scaring fund flows out of the industry altogether) towards return of capital vs CAPEX expansion investment - The 2020 oil crash that sent many O&G producers et al into bankruptcy (which also took even more oil supply offline)

Essentially, Stahl is describing the end of a long-running global commod and labor deflationary arbitrage from the collapse of the USSR and opening up of China, respectively. These are structural issues that (in addition to the most recent capex lulls and ESG barriers, post-2014 oil crash) would not necessarily be solved by any opex-inflation-led demand destruction. Deflationistas like Jeff Snider have used the past decades of steady and consistent deflation to indicate that the Fed’s QEs don’t work / fail to produce inflation28 — or are themselves actually deflationary — while Stahl argues that inflation (CPI + M2 growth) over these same periods has been counteracted by the commod and labor arbitrage described above. (Though, Snider in particular has left himself some wiggle room in such a scenario by delineating between “monetary” and “non-monetary” inflation and making it clear that he is speaking from the POV of monetary inflation, he’d likely classify the above arbitrage situation as non-monetary — and in the end his net deflation could ultimately be what we end up with and Stahl just ends up being wrong here).

Then there’s the disinflation/deflationista take of “high prices are about to take care of themselves — in the generally bad way“ wherein the bond market yields are signalling liquidity problems and an unwillingness of global capital to allocate into anything other than the most liquid of safe-haven assets. (Again, this honestly does not really damage the long term narrative of structural commod shortages). I will cover this more — as much as a simple non-macro person such as myself can — in the next part of this series when I cover the idea that the Fed is “trapped” and what may happen in regards to interest rates and various assets/industries in that context.

Lastly, we have the most wild POV — that I refuse to simply dismiss (as anyone who’s read “The World For Sale” could understand) — wherein there essentially vast oceans (literally, if they’re stored on oil tankers) of hidden barrels (currently being used as loan collateral) that could end up being dumped into the supply market for final sale — and disincentivize this kind of leveraging into the future — if the margin rates applied to global commod traders by their international banks were to rise with the Fed Funds Rate. Thus, under this theory, the commod shortage is not structural and heightened rates would crash oil prices, allow the IEA to suddenly “find” more barrels, stop OPEC+ from “missing” their quotas, and thus allow oil equities to remain suppressed for the long term (and certainly be touted as a Dem win for the 2022 midterms if the actual demand destruction from rate hikes is not too severe).

Commodities have been one of the only sectors going up in a time where tech and other crowded, once-reliable names/sectors for set-and-forget performance have been humbling many investors, both retail and institutional. Obviously, I’m on the long-energy train as well, but there are credible alternative realities where that corner of the stock market heat map is brought low with the rest of the investing space as well and is something I’m watching for.

Ultimately, the US is wither going to raise rates and implement some form of austerity measures (politically unpopular, but it could happen if they can somehow boil the frog slowly, quietly, and indirectly enough) or keep rates low and inflate our way out of debt… and (barring the appearance of a creative 3rd solution) I’m not ruling out a mixture of these two outcomes, either. From this POV, a portfolio allocated between some mix of solid, well-run inflation-beneficiaries (eg. mineral royalties and land owners) and interest rate beneficiaries (eg. banks (the ones that managed to not get too rocked during the 2008 crisis) and CME (which facilitates interest rate derivatives)) might be an attractive option.

Note this is not including the various small call-option type bets they have such as MIAX, Winland Hld., their crypto mining operations, and Diamon Std.

For some topics there are many more POVs that I have in my own notes than what I’m cataloging here, but I try to include the main ones w/out getting too much overlap.

UPDATE 20230114: I think this quick video does an OK summation of this idea re. the demographics pressure from EM countries, starting at 00:03:00…

The Russian market liberalization period known as Perestroika and glasnost policy reforms began in 1987 and saw many Western commodity trading firms flood the country (often in coordination with the Russian mafia) to take the place of centralized government planning in orchestrating production and sales pipelines. I’m aware that the USSR did trade with the US during the 1970s, but am not totally clear on the magnitude or impact of this.

UPDATE 20220903: The currently much-talked-about Zoltan Pozsar recently released a publication called “War And Industrial Policy” that begins with something fairly similar (and also cautions about these trends now fading)…

The low inflation world had three pillars: cheap immigrant labor keeping nominal wage growth “stagnant” in the U.S., cheap Chinese goods raising real wages amid stagnant nominal wages, and cheap Russian natural gas fueling German industry and Europe more broadly.

… and goes on to demarcate the fall of the Berlin Wall as the beginning of the West’s “lowlfation regime“:

That was just months before the Fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9th, 1989, an event we associate with the birth of globalization...

...and economists associate with the birth of the “lowflation” regime.

You can see this by looking at old HK Commentary publications from before they migrated their website via archive.org here: https://web.archive.org/web/20200921100140/https://horizonkinetics.com/commentary-type/commentary-archive/

The 2018 commentaries were the earliest I can see HK starting to talk about inflation (TBH, if it were too much earlier, I question whether they were just simply a broken clock whose hour had finally come around). When you click on any particular commentary link, you need to change the URL from looking like “https://web.archive.org/web/20200921100140/https://horizonkinetics.com/wp-content/uploads/docs/Q3%202015%20Commentary_FINAL_footnote.pdf” to just “https://web.archive.org/web/20201109034443/https://horizonkinetics.com/wp-content/uploads/Q2-2018-Commentary_FINAL.pdf” and scroll the time machine snapshot back to before ~2020 (when HK migrated their website), else you won’t be able to see any content. I assume this is because the links on the main Commentary page expect to point to a Word Press CDN — that no longer exists — but luckily the actual commentary URL that the CDN would redirect to have also been archived.

Though to this I’d like to bring up the cratering of M2 velocity at the same time

Though velocity is just a product of record high M2 supply vs a stagnant or declining GDP, see https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesfinancecouncil/2022/04/25/money-velocity-is-at-an-all-time-low-why-does-it-matter/?sh=6c9a9acb3dfa

We can see how the spread of M2 vs GDP has changed since 2020, here:

Here we can see how much of that M2 is simply being held as bank reserves (~16%), rather than actually circulating in the economy:

I’d also believe that they were just trying to get into oil equities and better prices for their clients by declaring some public bearish position in an attempt to move markets in the short term.

While Raskin is no longer up for confirmation, the example is still illustrative of the kind of wild anti-fossil-fuel zealotry being pushed by Dems at the moment. I don’t think this is a very controversial statement.

I used the widget here: https://markets.businessinsider.com/commodities/oil-price

See here for more details on this: https://wraltechwire.com/2022/04/06/recession-expectations-short-sellers-are-starting-to-bet-against-americas-economy/

You can look up more of Snider’s work or interviews — or any other deflationista take — for more info on what the general global deflation bulls’ POV is (eg. China slowing down since 2019, etc).

Not a macro guy, but that is my general understanding

Though we should also keep in mind that the price of oil futures did actually go totally negative in the initial panic of 2020.

Though there are many other available interpretations of what/where these “missing” IEA barrels are (eg. https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/How-The-IEA-Lost-200-Million-Oil-Barrels.html)

Thus, I’d rather FRMO’s shortage explanation be the correct one and that Western govs simply wake up to reality and abandon their fossil-free vision of the future in place of a more accommodating energy policy that gives the fossil fuel industry guarantees in the long run to ensure profitability of making long-term CAPEX investments today.

*Update 20220705: Here’s a recent example of the kind of their unsubstantiated claims — that I, yet, have a hard time dismissing:

Rule 15c3-1 requires a U.S. broker-dealer to retain control of any fully paid and excess margin securities in excess of 140% of a customer’s debit balance. […] U.K. broker-dealers face no statutory or regulatory threshold limitations on the use of client assets, although the CASS rules require explicit contractual rights to use assets that remain “client assets.”

Rehypothecation: Examples and What You Need to Know

Rehypothecation is a practice whereby banks and brokers use, for their own purposes, assets that have been posted as collateral by their clients.

The Fed - The Ins and Outs of Collateral Re-use

The use and re-use of collateral can create long "collateral chains" in which one security is used for multiple transactions.

Margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives

To ensure that assets collected as collateral for initial and variation margin purposes can be liquidated in a reasonable amount of time to generate proceeds ...

Standardized Approach for Calculating the Exposure Amount ...

Netting multiple contracts against each other can substantially reduce ... The assumptions of zero fair value and zero collateral allow for ...

“But the key point is that this futures contract will not be held open to the expiry date at the original price unless the physical market price – which is set by physical supply and demand – is actually at that price at that specific point in time. If the physical price is lower or higher, then the futures contract will be closed out through a matching purchase or sale and a profit or loss will be taken.

I managed the International Petroleum Exchange’s Gas Oil contract for six years, which was deliverable in North West Europe, and the final minutes of trading before contract expiry were Europe’s greatest game of ‘chicken’.

Moreover, no IPE broker in his right mind would dream (because the broker was responsible to the London Clearing House for defaults) of letting a financial investor with no capability of making or taking delivery hold a position into the last month before delivery. And if a broker was not in his right mind, it was my job to act under the exchange rules to ensure such positions were liquidated.

In other markets, the ability to own physical commodities – eg through ownership of warehouse warrants – is much more straightforward for investors. But the logistics of oil and oil products are such that financial investors are simply incapable of participating in the physical market. In my view the use of position limits for financial investors in crude oil and oil products is of little or no use if the clearing house, exchange and brokers are doing their job.

Finally, now that the US WTI contract is just the tail on the Brent/BFOE physical market dog, this discussion has moved on, since the ICE Brent/BFOE futures contract is in fact settled in cash against an index based on trading in the BFOE forward market, with no physical delivery. It is simply a straightforward financial bet in relation to the routinely manipulated underlying BFOE physical market price. ie the question of convergence does not arise.” —- https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/01/chris-cook-naked-oil.html

Looking at the WTI spot vs forward calendar spreads here (couldn’t find one for Brent): https://en.macromicro.me/charts/4379/wti-intramarket-spread

See https://www.alhambrapartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Why-QE-Will-Never-Work.pdf

None of the major economies that have undertaken QE can show definitive evidence of its efficacy, always seeming to need more. Not only are there serious questions about growth in each but inflation is curiously absent and getting more so all the time despite radical balance sheet expansion.

This was originally published around 2017, but Snider as generally kept with this view since then.

You don’t have to pay close attention to have realized everything being said now has been said to death at several points along the last decade or so. Just three years ago, 2017, absolute hysteria. Same with 2014, though more “transitory” then than hysterical.

Each time, huge spike predicted none ever materializes. Why doesn’t the media, or central bankers, believe people notice these things? Ideology is a powerful, powerful drug. The opiate of the “experts.”

“Research on the effectiveness of earlier quantitative easing has yielded mixed results, with most pointing to limited effects on economic activity. While most papers found evidence that quantitative easing helped reduce yields, its effect on economic activity and inflation was found to be small.”