$LB (LandBridge): An exchange trading floor of the Delaware basin

My 2 cents on LB's 273,000 surface acres and their H2O to I/O aspirations

TLDR

If the famous oil royalty company, Texas Pacific Land Corp (TPL), is the “ETF of the Permian basin”, then LandBridge (LB) is an exchange trading floor of the Delaware. LB owns uniquely positioned surface acreage in the Delaware basin and has an integrated relationship with WaterBridge (WB) midstream water management, which shares the same management team and majority owner. The both companies benefit from WB/LB’s ability to provide oil companies —and other water users and recyclers— with a path for a more efficient permitting and development process in the Delaware basin by virtue of this relationship (vs other water pipeline networks in the area that may need to negotiate with multiple land owners during the permitting/development process).

WB collects fees on the volumes of water transported, treated, and/or disposed of for customers through their pipelines and at their facilities, while LB collects resource sales, easements, and surface use royalties on water sourced from, infrastructure atop of, and waste water disposed of on their lands —usually from WB 1. The positioning and scale of LB’s acreage also acts as a call option on all other manner of surface use demand that may require water, energy, and acreage in the Delaware basin.

However, IDK that, at a high level, the growth expectations baked into the current price are a great bet to take and a lot of the near- to mid-term price action seems to depend on a tug of war between Jevon’s Paradox driving greater total data center capacity and infrastructure demand vs innovation-driven LLM kWh-per-token deflation —with LB longs rooting for the former.

I’d be a more willing buyer in the sub-$55/sh range at the moment.

.

While I own a good amount of shares 2, I’m not actually too certain that the stock is a particularly great buy right now. However, I thought it would be good time to set down some thoughts on the name while the year is just beginning and LB set to have their earning call tomorrow. (There’s always more to learn, questions to ask, and threads to pull, but just wanted to convert some of my major existing notes from spreadsheet cells and textfile notes-to-self into something more centralized/structured and will add more down the road).

Business

I think LB’s advantage can be summed up as owning uniquely positioned tracts of land that are set up to act as a (maintenance) 3 capex-light platform, connected by a large network of water handling pipeline operations via coordination with LB’s sister company, WaterBridge (WB), to service the fracking industry (and any other type of infrastructure that requires cheap and/or proximate access to land, energy, and water) in the Delaware basin. Both LB and WB share the same management team and are both majority owned by Five Point Energy LLC.

WB is the largest pure-play water midstream company in the US and operates a large-scale network of pipelines and other infrastructure in the Delaware basin 4. LB has a network advantage in the Delaware basin, vs other acreage owners that might compete with selling/leasing resources or acreage for similar use cases, that stems from LB and WB’s integrated operations due to their shared management team and ownership. WB collects fees on the volumes of water transported, treated, and/or disposed of for customers through their pipelines and facilities, while LB collects resource sales (eg. of brackish water and caliche5), easements fees, and surface use royalties on resources extracted from, infrastructure atop of, and waste water disposed of on their lands.

If TPL is the “ETF of the Permian basin” 6, then I look at LB as an exchange (of the Delaware sub-basin), where the exchange extracts volume-based fees on all operations that cross through the platform/acreage, the trading floor network/connectivity operations are handled by WaterBridge 7, and all the various easement users, resource buyers, and royalty payers are the exchange members.

(Base image source: https://www.sec.gov/divisions/marketreg/marketinfo/nysemi.htm)

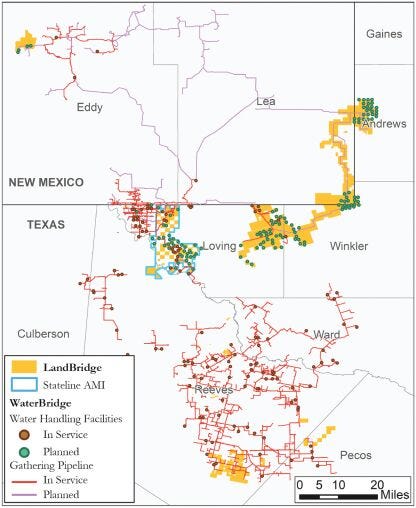

Compare this to a map of WB’s developing pipeline network to get a sense of the breadth of the network that LB will be a platform for:

(“WaterBridge Assets Map”, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1995807/000119312524172433/d752700d424b4.htm; note that this older map does not include the Wolf Bone Ranch property, acquired in December 2024, that sits near the eastern corner of Reeves county, below the Ward county line which can be seen on pg.12 in the more up-to-date prospectus here).

(For future reference, LB’s convention is to refer to the acreage north of the lateral southern New Mexico - Texas border as their “Northern position”, the acreage within the horizontal bounds approximately traced by the borders of upper and lower Winkler county as their “Stateline position”, and everything below Loving/Winkler southern border as the “Southern position”)

Note that the blue outlined area of mutual interest (“AMI”) is shared with the popular royalty company, Texas Pacific Land Company (TPL), which owns the non-LB acreage in the checkerboard pattern within that area. We’ll see in a few other maps that show that this area at the intersection of the Eddy, Lea, and Loving county lines gets a lot of use in terms of water handling operations.

.

By the way, just because the northern network looks sparse, it does not mean that it cannot service a lot of the surrounding —or distant— acreage. (The irrelevancy of contiguous physical connection when it comes to getting produced water from the wellhead to a pipeline will also be evident when we look at the pipeline maps of WB’s comps in the area; contracted acreage that a pipeline network may service need not be physically connected to the main lines themselves).

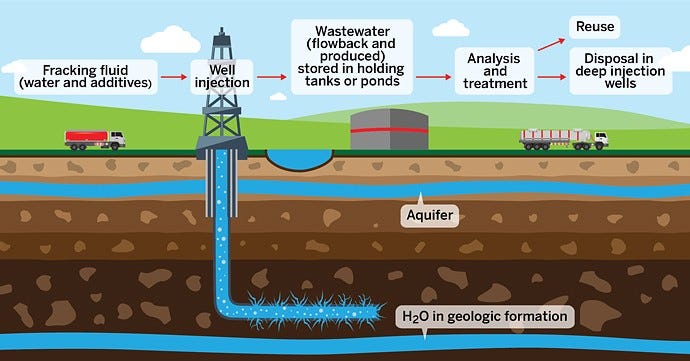

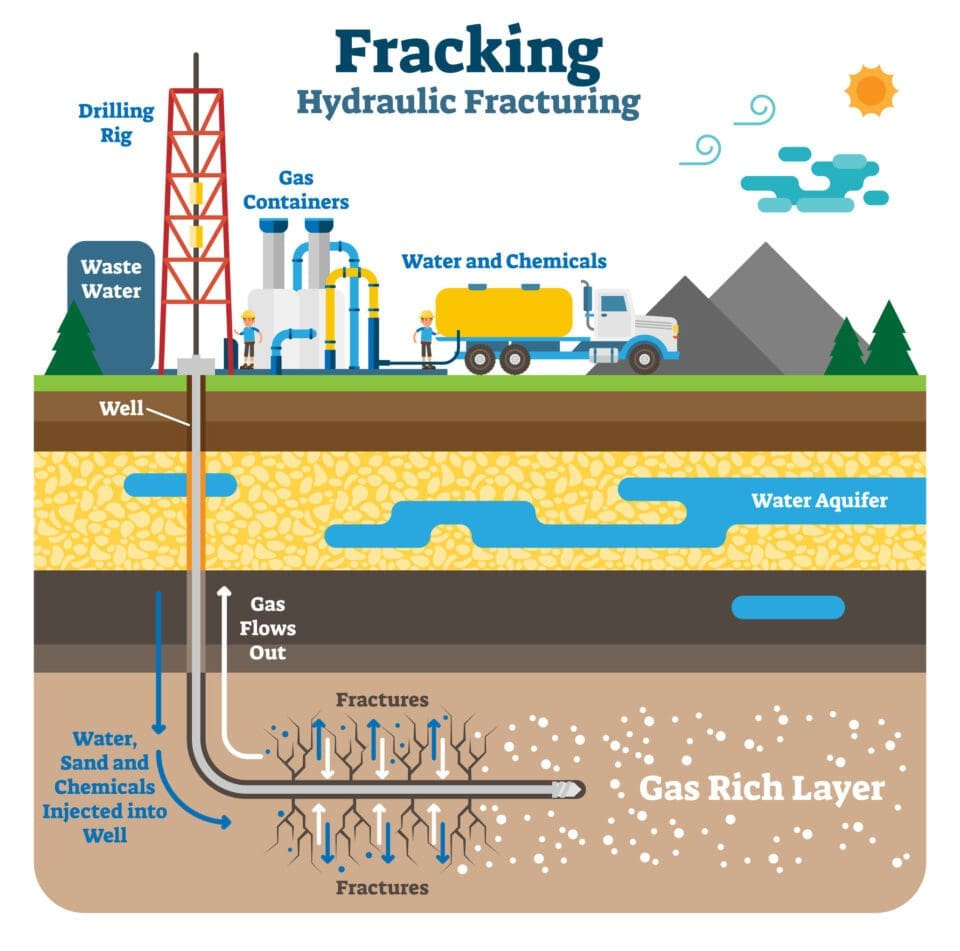

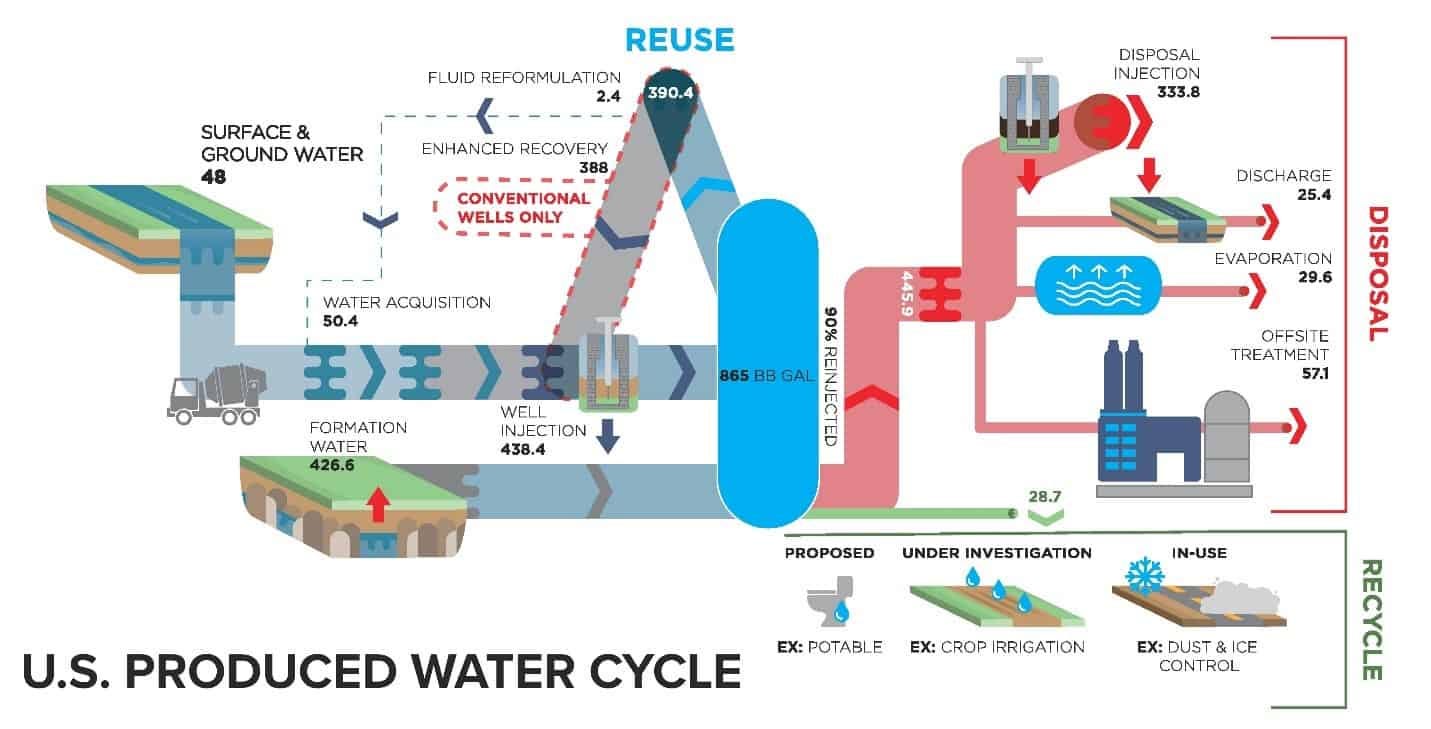

Aside from selling water to fracking operations in the basin, one of LB’s main operations for which they partner with WB comes from handling “produced water” for oil & gas operators. Produced water is the industrial waste byproduct of fracking and oil extraction that comes from both fracking “flowback” and naturally occurring water in geological formations that must be properly disposed of 8. After separation from the extracted oil and gas at the wellhead, it is collected and stored in tanks on site. It can then be collected and transported to water treatment facilities (or pipeline connection points) by water tanker trucks. An increasingly common trend in the Delaware basin is for storage tanks to be directly connected to small gathering lines (think of branches in a tree) that all converge from the wells in an area (think of these as the leaves) to the main pipeline (think of this as the tree trunk) 9 10 —it really just depends on cost and demand for tanker trucks. However it’s transported, the waste water ultimately ends up at a facility to either recycle/reuse or treat/dispose of it (typically via injection back into the earth), hopefully on LB acreage where they can collect a royalty per barrel handled (think of these like the ends of a tree’s roots).

.

Something to note about pipelines like WB’s is that they have a kind of local monopoly/oligopoly advantage where it costs less for an incumbent to extend an existing pipeline rather than for a new entrant to try to build out a whole new network to compete with the incumbent —a similar dynamic as was seen with railroads in the 1800s 11. Given WB and LB’s close integration via shared management team and existing agreements, LB also benefits from those network effects as they are able to coordinate development plans. (I think of the relationship between Diamondback Energy (E&P) and Viper Energy (mineral rights owner) as being somewhat analogous). For example, one of LB’s biggest drivers of expected 2025 EBITDA is the increased surface use royalties from the handling of produced water expected from a long-term partnership struck in August 2023 between WB and E&P company, Devon Energy, where WB will handle all of Devon’s produced-water within a large area of the Delaware basin, which will ultimately result in increased use of LB lands on which WB assets handle produced-water treatment and disposal. 12 13

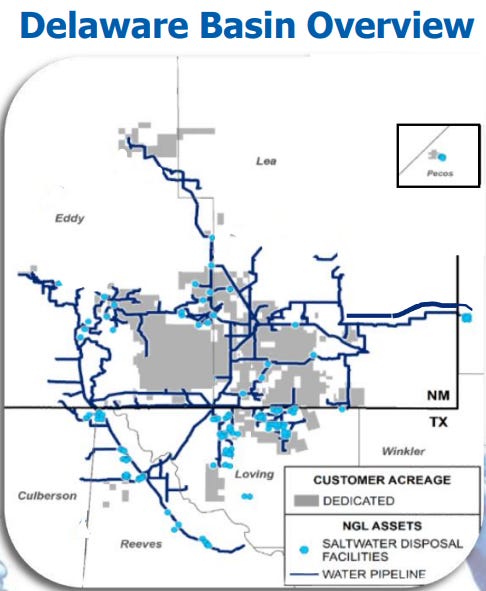

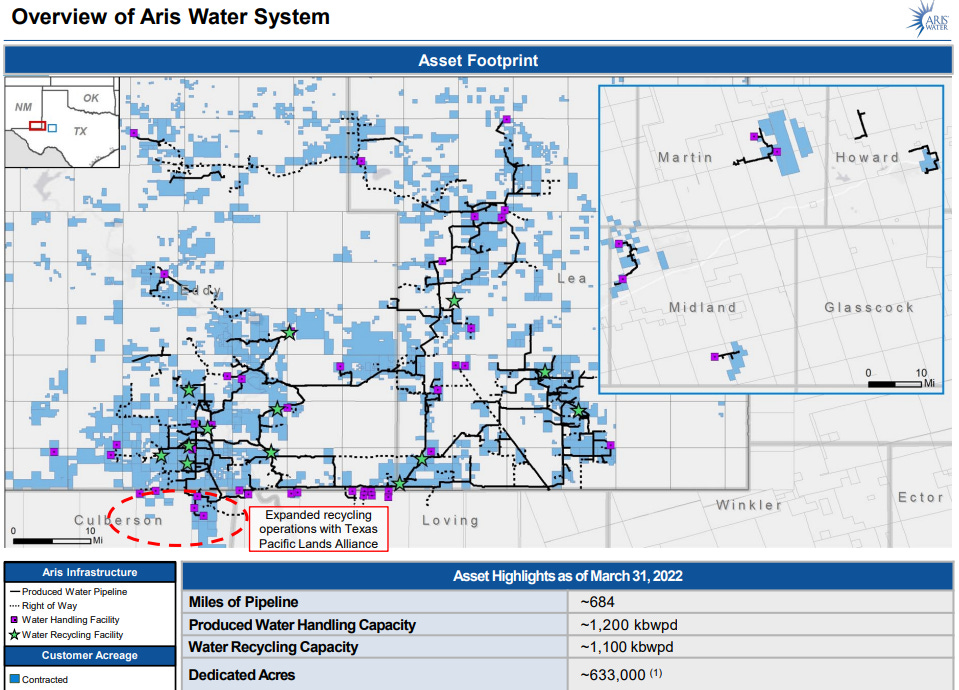

We can see the extent to which the other water handling pipelines in the area (NGL LP and Aris Water Systems) avoid —or overlap— each other by looking at a map of their networks in the area.

(https://irp.cdn-website.com/3038c594/files/uploaded/NGL_EC_Deck_3Q25.pdf; https://eic.energy/uploads/aris-water-solutions-eic-fireside_vf.pdf)

Here’s those same maps overlapped with WB’s network development plans (and LB’s surface acreage) for visual reference (it’s a bit blurry because of the overlapping and my bad photoshop skills, but we can see how WB is planning to move into the gaps of the other players’ existing pipeline network and contracted acreage):

NGL owns about 50% of the lands on which their facilities are located 14. Based on other hints from NGL’s 2024 10K, we can assume that the NGL-owned land is mostly on the Texas side —or at least that what they’d like— as the company recently sold acreage in both Nex Mexico counties of Eddy and Lea the basin 15. Meanwhile, if one examines the NGL pipeline network and facilities that lie right below the Eddy and Lea county lines, it appears that those NGL assets rest upon the LB/TPL AMI.

Likewise for the Aris asset map, for which I could find no evidence that they own any of their facility acreage, they plainly mention in their Q2 2024 earnings call that they “have relationships with landowners like Texas Pacific […] where we have the ability to go ahead and permit on TPL land and then drill as needed.” Conversely, the WB/LB relationship gives the added advantage of making it easier for customers to work with WB as the company can coordinate with LB for planning, permitting, and facility development, vs other pipeline operators that do not have as integrated a relationship with the various surface owners they must negotiate with to host their facilities.

“[O]n the WaterBridge side, continue to see good commercial traction. I think that's largely because of the land and the pore space access that we have via LandBridge. And I think conversely, to LandBridge's benefit here, we're seeing the synergies of that WaterBridge relationship given the fact that all of these commercial wins WaterBridge is achieving are just working in the benefit of LandBridge in the form of those [surface use] royalties [for produced water disposal]. And so part of the thesis from the get-go out of the gate was the water company and the land company really serve each other well.” ~~~ LB CFO, Scott McNeely, LB Q3 2024 Earnings Call

One thing I’d point out is that Aris’ various water management facilities are mainly situated in the New Mexico side of the basin, whereas we can see from WB’s pipeline map that WB will offer greater capacity for New Mexico operators to access the less-regulated Texas jurisdiction for water sourcing and disposal by plotting LB acreage and WB facilities on the Texas side of the New Mexico border —as NGL appears to be doing via their pipelines that extend into Texas’ Reeves and Andrews counties.

.

Aside from the benefit of WB’s network effects, much of LB’s acreage also have a unique intersection of advantageous geological characteristics that make their positions particularly well suited to serve operators in the Delaware basin.

As can be seen from the middle images in the composite above, LB acreage is nearby to areas in the Delaware basin that have…

+ High O&G estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) (representing the total amount of oil and natural gas expected to be recovered over the life of a well) 16, thus attracting O&G operators.

+ High water-to-oil ratios (WOR), where the geology of the area results in oil wells that create high levels of produced water byproduct relative to the barrels of oil extracted. This creates demand for water management services such as those offered by WB/LB to take away and recycle of dispose of this waste water. The WOR and total absolute amount of produced water from O&G activity the Permian basin has been rising over time and this trend is projected to continue. 17 Additionally, as wells remain in production, they can be drilled to extend horizontally (laterally) —as well as bend and curve as needed— and these longer laterals require more water for fracking as the fluid has a larger surface area to cover to fracture, thus requiring a greater volume of water to create the necessary pressure.

… Meanwhile, LB acreage itself sits atop geology with high capacity for waste water disposal, having both high porosity (lots of empty space existing in the formations) and permeability (water can move through / be injected easily into the space). These nearby or underlying geological advantages are all mentioned in their prospectus, which you can find here (or here, which is more recent and includes a more up-to-date map of LB’s expanded acreage in Reeves and Lea counties).

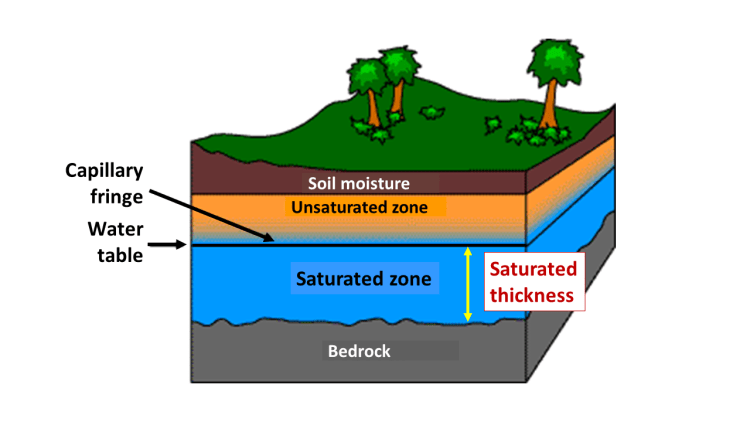

Something that is not mentioned in the prospectus is the unique thickness of aquifer formations underlying LB acreage, granting the company access to large volumes of (brackish) water; LB’s Stateline position sitting atop the the Capitan Reef Complex minor aquifer within the major Pecos aquifer 18. It may be interesting to compare this aquifer map (below) to the map of TPL and LB acreage displayed earlier in this post. LB covers some of the thickest sections of the aquifer (ie. higher water yield potential) 19 in Winkler county along the NM-TX border at some of the lowest elevations (giving those sections a greater rate of recharge as water flows from formation outcrops and zones of higher elevations to lower ones). 20

(https://www.twdb.texas.gov/publications/reports/numbered_reports/doc/R382_PecosValley.pdf, Figure 6-5; I didn’t want to just dump a bunch of maps in this post —any more than I already have— but I also found the section “6.1.4 Structural geometry” of this study to be very illustrative, for those interested in seeing the underlying cross-sectional shapes of the geology).

As mentioned earlier, LB’s Stateline and Northern positions also create the most direct opportunities for New Mexico operators to take advantage of the NM-TX regulatory arbitrage arising from the relative laxity of regulations on the Texas side of the border (as opposed to New Mexico operators trying to gets those same resource infrastructure projects permitted and developed on their own side of the border).

“In contrast to New Mexico, Texas generally provides a more favorable regulatory environment for produced water permitting. Between January 1, 2021 and March 31, 2024, the Texas produced water permitting process has taken an average of 171 days from initial submission to approval for produced water handling facilities located in the Delaware Basin (as defined by the EIA’s Permian Sub-Basin boundary), compared to an average of 655 days in New Mexico for produced water handling facilities located in the Delaware Basin over the same time period. Furthermore, we believe that New Mexico regulatory agencies have been less likely to approve shallow geological produced water handling wells. […] The combination of favorable geological characteristics and a comparatively less restrictive regulatory environment drives increased demand for produced water handling facilities on the Texas side of the Texas-New Mexico state border. […] New Mexico also presents a more restrictive regulatory and hydrological environment for sourcing brackish water used for oil and natural gas well completion activity. As a result, much of the brackish water supplied to the oil and natural gas industry in New Mexico is sourced from Texas. Our Stateline and Northern Positions contain significant underground brackish water sources from which brackish water can be produced for sale to companies that deliver this water to E&P companies in New Mexico for use in their drilling and completion activities.” ~~~ LB prospectus, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1995807/000119312524172433/d752700d424b4.htm

(This regulatory differential may soon shrink a bit due to New Mexico’s greater amount of federal lands 21 which will be affected by Trump’s recent executive orders related to US energy policy which 1] directs agencies to review regulations burdening domestic energy resource development as and 2] orders the expedited permitting for energy projects deemed essential for national security 22. This differential compression may be offset by an overall increase in drilling activity in the Permian as new energy secretary Chris Wright works to enact Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” policy agenda, which in terms of what can actually be done looks to be more like “deregulate, baby, deregulate” 23. The President is also looking to decrease taxes for the O&G industry and expand LNG export capacity 24 in what appears to be a way to keep operators profitable while he and Treasury Secretary Bessent work to bring oil price to the $50/bbl level.)

Taking the exchange analogy, LB’s Texas acreage positioning along the NM border combined with WB’s pipeline network between the states, making it the closest and most direct route to access less-regulatory-burdened water sourcing and disposal sites in Texas, is akin to how the US OTC Markets exchange acts as the cheapest and least-regulatory-burdened route for foreign companies to access US capital markets (“capital markets” in this case being water, land, and disposal pore space). One difference being that —unlike the greatly reduced subset of total US investors/capital that are willing and able to invest in OTC securities— the water sourcing and disposal geology on LB’s Stateline acreage is as good, if not better, than anywhere else in the Delaware basin. That is, unlike the less-efficient execution and lower liquidity of US OTC markets vs other major exchanges, LB’s border acreage lies in the more regulation-lax environment of Texas (ie. quick transaction “execution”) and sits atop some of the thickest parts of the Capitan aquifer for water sourcing as well as above high capacity pore space for water disposal (ie. high “liquidity”).

LB acreage is also located in areas with lower population density (ie. lower NIMBY-ism). The ability for LB to provide projects with access to energy and water all on low-NIMBY acreage is mentioned by Five Point CEO (and LB Chairman), David Capobianco, in a recent interview here:

“[F]or instance Loving County, if it were a country itself, it would be a top 10 or 15 oil producing Nation. It’s got a population of about 130, to put it in context. So there are massive swaths of land with very few people and that’s unique because nobody cares about seeing your data center, your water source is not taking from population center water sources, and your power can be built and developed for you on your own site [eg. via off-grid gas turbine].”

On the topic of data centers, Texas —with it’s cheap energy, large area, and business-friendly regulatory environment— is presently the second largest market for data center development in the US behind North Virginia 25 26, the latter of which is seeing increasing community push-back on additional data centers being constructed in the state 27. Note that the vast majority of data centers in Texas are in the north Texas Dallas / Fort Worth (DFW) area, due to existing robust power and telecom/fiber infrastructure (to actually get energy in and data out of the facilities), proximity to other businesses (ie. existing and potential customers), proximity to universities (ie. potential employees), as well as hosting the DFW International Airport (one of the largest in the US) 28 —all things that are lacking in the counties of LB’s west Texas Stateline position.

However, as the number and scale of data centers in Texas continue to grow, they will increasingly come into competition with residents for energy, space, and water resources if they continue to be built in the DFW area and the prediction that LB longs would also be betting on is that this is a politically untenable situation in the long run and that new data centers will ultimately have to move off-grid to directly draw power from natural gas lines into co-located turbines in, say, the Permian 29. There are a few data centers in the west Texas area where LB operates and one of those few —a data center owned by, crypto miner, Core Scientific— is actually located on LB acreage near Pecos city in Reeves county (the blue (1) dot nearest the New Mexico corner border in the map below) 30.

A final note: LB makes relatively little revenues from ownership of oil and gas royalties. This translates into lower sensitivity to oil and gas prices; unlike other land owners in the Permian like TPL or VNOM, LB is more focused on volumes / activity. This can be a double-edged sword that hurts returns if oil prices rise (though they’d benefit indirectly from the likely subsequent increase in drilling activity for Permian operators), but dulls the impact of any down-swings in oil prices (such as those that might come if President Trump is successful in lowering oil prices and increasing total hydrocarbon production in the US).

Success mode

Here is the full suite of the company’s aspired use cases for their land (of these aspired use cases, I’ve circled the types that I know LB currently hosts):

Much of the bullish narrative around LB stems from the anticipation of data centers being built in the Permian (for the various reasons already mentioned) and LB being able to capitalize in their massive needs for continuous access to cheap energy, water cooling, and surface acreage. The term “data center” is frequently mentioned in the company prospectus and at every earnings call since the company’s 2H2024 IPO. Currently, LB is in the initial phases of possibly hosting a single data center for another Five Point sister company, Powered Land Partners 31, but management has alluded to 5-6 other data center projects that may be interested in developing with LB 32.

The current overall trends seems to be in favor of LB’s data center growth thesis. We can examine the projections for the various public AI-related companies and see how they intend to significantly increase their spending on data center capex for 2025 relative to the previous years since OpenAI launched ChatGPT:

Valuation

Here I have LB valued at various multiples (including the current implied multiple) to management’s 2025 EBITDA projections, with my assumptions noted, with and without an additional expectation value of future data center projects that are already prospectively looking at LB acreage for development. We also can see the implied growth rates for those price targets such as would be required for a simple DCF to reach the same price conclusions.

(Here DC is short for data center)

Note that, while I put a 6yr estimate on all of these facilities being built, President Trump has made AI dominance and energy infrastructure development key elements of his policy goals and intends to use deregulation a key lever towards those ends.

To look for an example to demonstrate the magnitude and uses cases for which red-tape-cutting could speed energy infrastructure development, consider the data center that was built by Elon Musk (apparently without first getting the proper permitting and circumventing local government approval) to power X/Twitter’s Grok AI. Rather than using a connection to the local electrical grid, the facility was initially built to rely primarily on gas turbines and was built in under a month 33.

We can examine the implied growth rates of the different price levels as compared to the segment-weighted average growth rate for the, more mature, Permian land owner TPL over time. (Again, TPL is the more mature company and one should consider the fact that WB’s pipeline network and LB’s acreage is still growing as management continues to seek acquisition opportunities).

.

For my money, I’d be willing to take the longterm TPL multiple of 28x on LB, but at the price point that assumes zero data centers actually get built, for a buy range around $50/sh.

.

We can also compare LB’s valuation multiple relative to other, more directly-associated, AI-beneficiaries:

Risks

Let’s just assume that tech companies find LB’s acreage suitable for data center construction (never mind the additional challenges posed by the Permian’s higher temperatures that may strain cooling systems, lack of existing fiber connectivity, danger to equipment from frequent dust storms due to the flat and arid environment, and seismic risk from local fracking operations vs the DFW area which does not have these issues). Some other risk factors that I think could be important issues to monitor are…

At least narrative-wise, the data center angle has been important to LB’s price action. Over time, increased land acquisitions in combination with WB’s pipeline buildout may alone be enough to justify LB’s implied growth expectations (note that most of the growth in their 2025 EBITDA vs 2024 comes from a water-handling deal negotiated by WB and not anything related to data centers), but the price has been very sensitive to AI-related news. For example, between the release of the free and open-source Chinese DeepSeek-R1 LLM model on Jan 21 and the rapid ascent of the company’s associated chatbot app to the top spot on the Apple and Google app stores by the 28th 34 35, US AI stocks slumped with the tech-heavy NASDAQ falling 3% and NVIDIA falling 20% 36. Meanwhile, LB stock fell by a similar 23%, peak to trough.

(Sudden and unexpected) deflation of data center kWh requirements (and subsequent water and acreage requirements) for processing the same volume of prompting and inference tokens via rapid step-wise tech and algorithm innovations, a la DeepSeek 37. There is a tug of war between Jevon’s Paradox (to increase total data center capacity / infrastructure demand) vs innovation-driven kWh-per-token deflation.

Earthquake risk from continued produced water injection disposal in the Permian may make the area less attractive for large data center investments and other non-fracking-related projects. Looking into why DFW is such a popular data center hub in Texas, one of the reason I continually see is the low risk of dangerous weather conditions that may result in damage to the expensive equipment housed in those facilities 38. Would the increasing risk of earthquakes in the Permian make the area a less attractive location for hosting data centers despite the cheap access to land, energy, and water? (My understanding is that earthquake risk in the Permian is localized to certain specific areas with certain geological characteristics and that there are ways to mitigate these risks by monitoring fault locations, subsurface pressure changes, and wastewater injection depths 39. Inversely, this could also make acreage that sits upon high capacity, lower pressure, pore space more valuable.)

Here is a map of seismic activity from a 2018 study of the Permian:

(The A,B,C lines indicate fault lines in the earth’s crust with line thickness representing decreasing confidence of the illustrated direction; I’m pretty sure the blue to yellow gradient illustrates increasing fault stress where yellow indicates higher built-up stress that can trigger an earthquake; red dots indicate locations of recorded earthquakes of varying magnitudes; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322907739_State_of_stress_in_the_Permian_Basin_Texas_and_New_Mexico_Implications_for_induced_seismicity)

Development of closed-loop water cooling systems vs conventional evaporative systems. Mass adoption of this technology would cause LB’s water advantage to be greatly diminished vs other locations. (See https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-cloud/blog/2024/12/09/sustainable-by-design-next-generation-datacenters-consume-zero-water-for-cooling/).

(This would be very bad for LB’s data center water sourcing story)

Existence of other contiguous, high-quality, (Texas-side) Permian acreage. While LB has tried to be strategic in their land acquisitions, in terms of where a data center might end up in the entire Permian basin, there are much larger land owners than LB (such as Apache, Occidental, and Chevron) that could host them and help to develop their necessary infrastructure 40. For example, Exxon owns twice as much land as LB and has recently announced plans to build a natural gas power plant specifically to contract with data center companies 41.

The developing ability / permitting to dispose of (treated) produced water directly into surface-level water sources, like the Pecos river, could affect the value of LB acreage for produced water injection disposal. “Certainly, there are opportunities working with the regulators and applying for the appropriate permits for surface discharge into the Pecos River. That is an alternative. We are actively looking at that, as are others. And I think you will see that continue to progress over the next year.” ~~~ ARIS founder and chairman, William Zartler, FY2024Q3 earnings call

A situation of declining productivity in Delaware basin that cannot be offset by longer laterals nor is offset by rising water-to-oil ratios, resulting in net declining water sourcing and recycling/disposal revenues.

.

WaterBridge accounted for 25% of LB's revenue for the nine months ended September 30, 2024 and this seems likely to hold for the full year numbers, which will be coming out on March 6 2025.

In terms of underlying via LEAPs my position is significant. Full disclosure, I sold most of my equity position after the DeepSeek shock in late Janurary for around a 10% loss in exchange for the calls. I explain a bit why I found the stock to be a bit of a gamble, and seemingly over-priced, later in the post.

While managing and maintaining their acreage is extremely capex- and opex-light, LB has been investing in expanding their land holdings and made several purchases in 2024 at a blended expected EBITDA yield of around 13% (per Special Call 11/22/24, https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/0001995807/000095017024129975/lb-20241118.htm). Aside from interest payments on debt, which appears to mostly have been used to finance further land acquisitions, most of LB’s ITDA expenses on their EBITDA comes from amortization of surface use agreements and water rights contracts that they’ve acquired as part of their various land deals (see section “Fair Value Measurements” in FY2024Q3 10Q). That is to say, as mentioned, they have little to no maintenance capex and so EBITDA can be taken as a close approximation to earnings for this business and these acquisitions.

I believe the largest in the Delaware basin is NGL Energy Partners, which competes with WB.

Basically a kind of mixture of sand, clay, and gravel that is used for construction or road-building material. My understanding is that businesses operating on LB land are required to buy all caliche that they use on the land from LB themselves. So, for example, a business that wants to build a road on LB acreage —say, for water tanker trucks to access a produced water treatment facility— would need to pay LB easement fees to build and keep the road as well as purchase all of the caliche they use to construct that road in the first place from LB.

Per TPL’s own presentation materials, https://www.texaspacific.com/investors/sec-filings/all-sec-filings/content/0001811074-21-000026/0001811074-21-000026.pdf

LB pays WB shared management fees as part of their shared services agreement that show up in LB’s SG&A; the management structure essentially “flows” down from WB to LB through this agreement.

See https://www.westernmidstream.com/midstream-101/,

https://lithiumharvest.com/knowledge/produced-water-treatment/what-is-produced-water-treatment/,

https://kimray.com/training/brief-guide-water-management-oil-and-gas-industry,

https://adi-analytics.com/2018/09/06/water-transportation-the-new-midstream-opportunity/,

and here for some references

See LB’s 2024Q3 earnings call for more on this discussion.

From LB’s 2024Q3 10Q… “Surface use royalties increased by $12.4 million, or 144%, to $21.0 million for the nine months ended September 30, 2024, as compared to $8.6 million for the nine months ended September 30, 2023.” Furthermore, “[e]asements and other surface-related revenues increased by $4.3 million, or 187%, to $6.6 million for the three months ended September 30, 2024, as compared to $2.3 million for the three months ended September 30, 2023. The increase was primarily attributable to oil and gas transportation and gathering pipelines and produced water handling infrastructure of $3.4 million”. That is, 79% of that same-period YoY easement revenue increase was due to WaterBridge infrastructure build-out (I assume largely due to the Devon Energy partnership). This is a major uplift to revenues and I wonder how sustainable this kind of growth will be going forward.

“We own the land on which 39 of the 89 water treatment and disposal facilities are located and we either have easements or lease the land on which the remaining water treatment and disposal facilities are located.” NGL 2024 10K

See “Dispositions” section in NGL 2024 10K

One can compare LB’s acreage and EUR maps with the production maps here, from 2019 —which also contain an interesting discussion on the nuance of oilfield acreage tiers, see https://jpt.spe.org/whats-difference-between-tier-1-and-tier-2-not-much. (There’s many other maps that show a similar story, but this is just example to check that management is telling a story consistent with everyone else’s understanding of the actual geology of the area).

Aquifer thickness refers to the vertical depth of water-bearing rock or sediment that can store and transmit groundwater. Think of aquifer thickness as the the height of the underground water container. Note that the entire thickness of an aquifer isn’t usually filled with just water, but rather filled with rock or sediment with pore spaces filled with water, see https://wellntel.com/farmers-should-track-aquifer-saturated-thickness-to-plan-crops-and-irrigation/ and https://www.kgs.ku.edu/HighPlains/atlas/apst.htm.

See here (https://www.texaspolicy.com/legewaterrights/) and here (https://www.texasenvironmentallaw.com/practice-areas/water-permits-rights/groundwater-permits-rights/) basic info on how (ground)water ownership rights relate to surface ownership rights in Texas.

“In New Mexico, half of Permian production in 2020 came from wells on federal lands. All production in Texas is on private and state-owned land. Wells on federal leases are, on average, higher performing than those in other parts of the basin.” ~~~ https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2021/0304

eg…

We can guess this by simply looking at the data center map, zooming on Pecos and examining the highway pattern at the intersection (a cross shape angled north-west with an extra leg going southward), then comparing this pattern to a map of LB acreage + the fact that LB cites having contracted with *a* crypo miner —of which Core Scientific is one— in their most recent prospectus (“we have entered into various surface use agreements through which our customers have built and own or are developing infrastructure on our land, including […] a data center and a cryptocurrency facility, as of December 30, 2024.”).

(https://www.datacentermap.com/usa/texas/pecos/)

(https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1995807/000119312525014364/d898161d424b3.htm, see the yellow/beige LB acreage partially covered by the “Pecos” label on the map).

“On November 6, 2024, we entered into a lease development agreement for the development of a data center and related facilities on approximately 2,000 acres of our land in Reeves County, Texas. The counterparty to the agreement is a joint venture between a third-party developer and funds affiliated with our financial sponsor, Five Point Energy LLC.” ~~~ LB 2024Q3 10Q

Kevin MacCurdy: “Yes, following up on the data center, I just was curious if you guys have quantified how many data center and solar lease opportunities you had out there? And if you wanted to provide some high-level thoughts on what the potential revenue impact could be from either a single deal or from all the opportunities you see?”

Jason Long: “Yes, Kevin. So we've roughly identified 5 to 6 right off the bat from a data center standpoint. As far as you think about solar, one of the first data centers that we're focused on would be co-located with a large solar development, roughly 250 megawatts.”

LB 2024Q2 earnings call.