Notes on "How They Did It": Benjamin Graham

The necessity of lemons for lemonade and the operational leverage of other peoples' money

“Reading is forced meditation” —- David Senra (quoting a librarian whose name he couldn’t recall)

“Tell me who your heroes are and I’ll tell you how you’ll turn out to be.” —- Warren Buffett

I recently got a copy of Murray Stahl’s “How They Did It” and read it over the course of an NYC vacation in January where the cold impelled a lot of time spent indoors, allowing me to finish the book as well as the basic outlines and supplementary ideas for each section. Summarizing an entire book isn’t something I would normally think I’d find useful, but in this case I think there is value in the act of simply digitizing the ideas in some form for my own future reference, since —unlike many other famous contemporary investors’ writings— you can only get this book in hardcover edition1; it is not available as a PDF, Kindle, other online form, etc.

(Aside from being a high leverage way to distract yourself from the everyday market movements) one thing that I think is sort of interesting about books is that, often, their value is only realized/actualized over a long time horizon, while at the same time that value is not generally affected by interest rates —unlike what the market is experiencing first-hand with many other long-duration assets right now. In a more literal sense, Murray Stahl has mentioned that he is a collector of rare books2 and that they also double as a type of asset in some ways…

I'll say one other, in the world of rare assets, let's take something where there is potentially an infinite number of rare assets like rare books, really so many copies of first edition Charles Dickens. Okay. So Charles Dickens lived in 19th century, and their first editions of authors who lived in 20th century. That near fact you will have the accretion of every new authors, some of them might be better than Charles Dickens, it doesn't destroy the value of Charles Dickens first edition. The idea that is, someone is going to come up with a better technology than bitcoin, it doesn't destroy the value of bitcoin. It does what it’s supposed to do, and it's authenticated, it's a rare asset. —- https://seekingalpha.com/article/4502294-frmo-corporation-frmo-ceo-murray-stahl-on-q3-2022-results-earnings-call-transcript

Stahl has said that he became obsessed with reading auto/biographies when he reached a point of desperation after being told what he was learning in his college economics courses was not about “how to make a lot of money”, but about “how the economy fluctuates”3. He first started with reading about successful money makers and later extended into reading about anyone who ever succeeded in anything biography-worthy. This habit continued, at least, into his time at after college at Bankers Trust Company (coincidentally, BTC). Written in 2011 —nearly 20 years after Stahl left BTC to found Horizon Kinetics— the book is mostly composed of biographical vignettes of prominent investors or related periods throughout history.

To avoid a single monolithic article, I plan to slice this series into segments very closely approximating the delineation of the chapters in the book and in each section mix a description of the person or period covered in the chapter, the basic takeaways explicated therein (if any)4, as well as my own riffing or commentary (as I find that many ideas in the book can be related back to ideas that can be seen implemented in Stahl’s various investments, today).

Many of the chapters from the book either were originally freely published as memos by Horizon Kinetics (HK) or FRMO Corp or released on those sites at various points after the book’s publication and I’ve included links to those archived articles when possible (as most were not transferred over when they migrated websites in 2020) —as well as links to other publications I found relevant for the given topics.

If I’ve added multiple links for a section, I’ll add a star (★) next to the link that I’m pretty sure is the essay compiled in the book, if I could find it, so you can read it for yourself. I will also include a star in the sub-title of each post that contains a link to the original source, so that it’s obvious at a glance.

For those solely interested in the original essays included in the book, a section is included at the bottom on this post that lists each one in order that they appear in the book. Again, note that I was only able to find ~50% of them anywhere online, but I will add more if I come across any.

What came first: The famous Benjamin Graham or the Great Depression?

“I thanked the old man, a bit condescendingly no doubt, and said I would think over his suggestion. Then I hastened to put it out of my mind. Dix was not far from his dotage, he couldn't possibly understand my system of operations, his ideas were preposterous. As it happened he was 100 percent right and I 100 percent wrong. I have often wondered what my life would have been like if I had followed his advice. That it would have spared me much worry and regret I am sure; but whether my character and later career would have formed as they did after my ordeal by fire is another question.” —- Benjamin Graham (after being recommended to sell his portfolio by a random stranger in the midst of the Great Depression for the sake of his shareholders and his own quality of sleep)

While best known for authoring investing classics like “The Intelligent Investor” and “Security Analysis”, in 1996 Benjamin Graham also wrote an often-overlooked memoir titled “Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street” —which if you currently look on Goodreads only has ~200 ratings vs the ~115000 ratings for “The Intelligent Investor”.

One thing that Stahl mentions in this chapter is that if we try to “understand the scope of Graham’s interests, it is arguably easier to understand his view of the world.” I find this message interesting as it could also be said of the varying subjects of “How They Did It” itself as I find that many of the topics covered across the book have relevance to things observable in Stahl’s investments even today —I will go over these ideas in the relevant sections as they come up.

Before gaining the fame that would come from writing “Security Analysis” in 1934 and later “The Intelligent Investor” in 1945, Graham was simply a money manager of much lesser fame. In chapter 13 of his memoirs, Graham details his experiences as a money manager during the Great Depression. Between the years 1929 and 1932, during the onset of the depression, Benjamin Graham’s fund, the Benjamin Graham Joint Account, declined by 70% at its low-point. Something also noted here is that even the famous mentor of Warren Buffett himself —like many of his contemporaries— failed to anticipate the Great Depression (despite perhaps seeing/feeling it coming). We can see the chronicle of Graham’s experience right before, after, and throughout the depression in the memoirs, here…

“We both agreed that the stock market had advanced to inordinate heights, that the speculators had gone crazy, that respected investment bankers were indulging in inexcusable highjinks, and that the whole thing would have to end one day in a major crash. I recall Baruch's commenting on the ridiculous anomaly that combined an 8 percent rate for time-loans on stocks with dividend yields of only 2 percent. To which I replied, "That's true, and by the law of compensation we should expect someday to see the reverse — 2 percent time- money combined with an 8 percent dividend on good stocks." My prophecy was not far wrong as a picture of 1932 — and it was borne out precisely, under a different set of market circumstances, some twenty years later. What seems really strange now is that I could make a prediction of that kind in all seriousness, yet not have the sense to realize the dangers to which I continued to subject the Account's capital.” —- https://archive.org/details/memoirsofdeanofw00grah/page/251/mode/2up?view=theater

“Here was [the Benjamin Graham Joint Account’s] position in the middle of 1929: our capital was 2 [and 1/2] million; we had shown only a slight gain for the first half of 1929 (a fact that should have augured trouble ahead). We had a large number of hedging and arbitrage operations going, involving a long position of about 2 [and 1/2] million, offset by about an equal dollar volume of short sales. In our calculations these did not involve any net risk of consequence and so needed only a nominal part of our capital. We had in addition as much as 4 [and 1/2] million in true long positions, or investments of various types, against which we owed some 2 million. As margins were then figured, we calculated ours at about 125 percent; this was six times the brokers' minimum requirement and about three times what was generally considered a conservative margin. We were also convinced that all our long securities were intrinsically worth their market price. Although many of our issues were but little known to active Wall Street hands, similar ones had previously shown a praiseworthy tendency to come to life at a decent interval after we bought them and to give us the chance to sell them out at a nice profit, replacing them by other bargain issues which we were constantly digging up.” —- https://archive.org/details/memoirsofdeanofw00grah/page/253/mode/2up?view=theater (you also can read on a bit from this page in the link to see more detail on how Graham used preferreds in his fund; also note his carrying of 125% leverage right before the crash).

“Our loss for 1930 was a staggering 50 [and 1/2] percent; that for 1931 was 16 percent; but that for 1932 was only 3 percent — a com- parative triumph. The cumulative losses for 1929 through 1932 — before the tide turned — were thus 70 percent of our proud 2 [and 1/2] million capital of January 1929. But we had stubbornly continued to make quarterly distributions of [1 and 1/4] percent— charged to Jerry and my capital — and these cut the amount remaining at the end of 1932 to only 22 percent of the original figure. A number of the participants withdrew all or part of their capital. One of these was Bob Marony, who explained most apologetically that he had to have his funds to meet obligations elsewhere. (Fred Greenman told me then that Bob — the imperturbable, fighting Irishman — had burst into tears after disclosing the near-total loss of his fortune of far more than a million dollars.) We gave Marony his pro-rata share of the issues in our portfolio, against assumption of what was then a quite small debt.” —- https://archive.org/details/memoirsofdeanofw00grah/page/259/mode/2up?view=theater

“The chief burden on my mind was not so much the actual shrinkage of my fortune as the lengthy attrition, the repeated disappointments after the tide had seemed to turn, the ultimate uncertainty about whether the Depression and the losses would ever come to an end. Add to this the realization that I was responsible for the fortunes of many relatives and friends, that they were as apprehensive and distraught as I myself, and one may understand better the feeling of defeat and near-despair that almost overmastered me towards the end.” —- https://archive.org/details/memoirsofdeanofw00grah/page/261/mode/2up?view=theater

“The Crash reaffirmed parsimonious viewpoints and habits that had been ingrained in me by the tight financial situation of my early youth but which I had overcome almost completely in the years of success. I blamed myself not so much for my failure to protect myself against the disaster I had been predicting as for having slipped into an extravagant way of life which I hadn't the temperament or capacity to enjoy. I quickly convinced myself that the true key to material happiness lay in a modest standard of living which could be achieved with little difficulty under almost all economic conditions. I applied this new principle in two ways — one logical and creditable enough, the other quite small-minded.

It became my firm resolve never again to be maneuvered into ostentation, unnecessary luxury, or expenditures that I could not easily afford. The Beresford lease was a bitter but salutary lesson, and in the ensuing thirty-five years, I have avoided any and all real estate white elephants. But on another plane, that of purely personal spending, I must own that I carried economy much too far, and began once more to worry about dimes and quarters when tens of thousands of dollars were actually at stake.” —- https://archive.org/details/memoirsofdeanofw00grah/page/263/mode/2up?view=theater; The real estate “white elephant” here referring to his lavish residence at the time which he later decided to move out from (the Beresford Apartments, I believe)

“During the trying period of 1930 to 1932, I kept busy with many activities. I wrote three articles for Forbes Magazine, pointing out the extraordinary discrepancies between the low prices of important common stocks and the much larger current assets (even cash assets) that were behind each share. The title of one of those articles was "Is American Business Worth More Dead Than Alive?" a question that was to take an important place in financial phraseology. (Actually the phenomenon continued to affect the stock of many companies long after the end of the Great Depression.) I participated in many economic discussions with groups of various sorts. I continued to give my course at Columbia, though to much smaller classes, and in 1932 I set definitely to work on the textbook that I had first projected in the lush times of 1927. I asked Dave Dodd to collaborate with me on the book. […] it was to take a year and a half before the first edition of Security Analysis made its appearance.” —- https://archive.org/details/memoirsofdeanofw00grah/page/263/mode/2up?view=theater; an even stronger piece of evidence that the Depression is what made Ben Graham as the “Father of Value Investing” as he is known today.

… In any case, it should be noted that even nearly 100 years later to this day, the exact cause of the depression is still a topic of debate5.

Is there some flaw in value investing’s “margin of safety” principals —which Graham was presumably applying— that failed to actually realize a margin of safety in the Graham Joint Account during the Great Depression? Stahl argues that the takeaway here is that value investing is to be applied in determining the value of something against it’s present trading price, to find bargain buys, and not to be expected to provide protection against the left tails themselves that may create those opportunities in the first place.

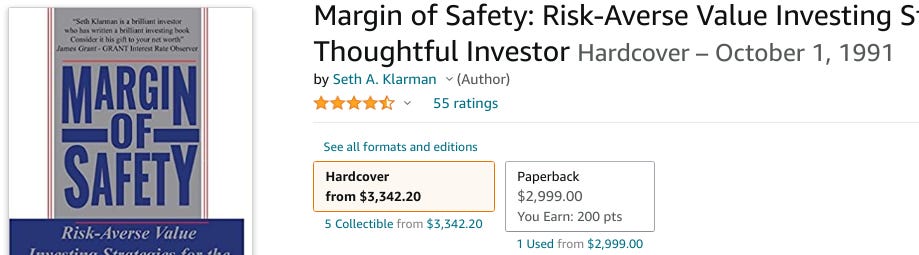

IMO, I would kinda intuitively think that traditional value investing should provide this downside protection given my understanding of the kind of net-net, NCAV investing that Graham was doing6 and certainly, ostensibly, not how I would think they'd behave by Seth Klarman's explanation of a “margin of safety”; In fact, here’s Klarman, in his own words7, talking directly about Graham and the supposed benefits of a margin of safety...

Benjamin Graham understood that an asset or business worth $1 today could be worth 75 cents or $1.25 in the near future. He also understood that he might even be wrong about today's value. Therefore Graham had no interest in paying $1 for $1 of value. There was no advantage in doing so, and losses could result. Graham was only interested in buying at a substantial discount from underlying value. By investing at a discount, he knew that he was unlikely to experience losses. The discount provided a margin of safety. —- Seth Klarman, “Margin of Safety”

… but OK (I may need to re-read that chapter of the memoirs)8.

One method that I do think that this excuse may more legitimately apply to is Michael Mauboussin’s “price implied expectations” investing approach, since it is more directly focused on looking at the present situation and current market consensus assumptions —which is also perhaps (philosophically, anyway) more aligned with what those like Stahl, Buffett, and Klarman mean when they talk about “value investing”. In any case, I think most investors can excuse the idea of valuing and investing in a business without necessarily trying to predict for “left-tail risk” —which are sort of unpredictable by definition9.

Stahl postulates that the economic collapse during the depression also produced bargains in the stock market and a durably traumatized investing public that, it could be argued (after receiving clemency from his Joint Account shareholders in the form of consenting to a resting of the fund's high-water mark and performance fees), are what made Graham’s investing fame possible. Graham was able to purchase quality businesses with robust dividend yields well in excess of the cost of debt at the time, while major discounts remained available well into the 1950s. From this he was able to produce 20% annualized returns following this initial market shock from 1936 to 1956 (when Graham ended his investment career) vs the broader stock market's 12%10.

Interestingly, Charlie Munger has mentioned that the Great Depression is what lead to Hitler (becoming Chancellor of Germany)11 and later WW2, which ironically is what Munger believes is what ultimately lifted the US back out of the Depression12.

One positive thing to take away here is that even a setback of a nearly 70% drawdown does not preclude the possibility of success (and through the continued and consistent application of rational investment principles rather than praying for dumb luck or a bailout by other means, no less).

This may also explain why FRMO has carried such a large cash position (about 20% of the company’s book value) for such a long time —perhaps waiting for an opportunity like Graham’s during the Great Depression.

As HK/FRMO co-founder Steve Bregman once remarked…

In our case, we don’t mind interim stock price volatility; we’re more concerned with long term returns. But the opportunity set for attractively priced securities is quite narrow, and the systemic risks quite great. One shouldn’t feel compelled to take one’s cash and place it at risk just because you’ve allocated it as available to be invested. In this regard, there are two additional features to portfolio practice we might add.

One is time diversification, which is not much discussed; discussion almost exclusively centers on security diversification. But the long-term return you get is powerfully determined by when you start: at the top of a market, or 6 months later at the bottom? […] There’s value in a measured approach to capital commitment, and with time comes opportunity.

The other element of cash is that its value is far more dynamic and elastic than people give it credit for — in that its purchasing power rises dramatically when other assets decline. Here’s a quick Rorschach test, an inkblot picture of a serious global trade war. What do you see? If you’re fully, optimally invested, as is said, in the various global equity and emerging markets and investment grade and non-investment grade bond funds, it might look like a terrible storm. If you have a meaningful cash reserve, it might look a lot like a candy jar, for heaven knows what goodies might be inside.

Though I’d also like to complain that Stahl and Bregman (S&B, as I may refer to them in future post in this series) failed deploy any of that cash during the lows of the unprecedented global economic shutdown and pessimism of the COVID-19 pandemic —of course, so too did even Warren Buffett who in fact sold out of Berkshire’s entire airline exposure during this same time despite having commented that Berkshire "certainly won't be selling" in response to the very first blushes of the COVID panic in late February 202013. So, perhaps a bit of understanding is warranted here.

Further related reading:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160512141243/http://horizonkinetics.com/docs/Contrarian%20Compendium%2011-08.pdf (see, “Ben Graham: Investor and Person”)

The operational leverage of other peoples’ money

Graham likely earned much closer to —if not greater than— his touted 20% annualized return vs his Graham Joint Account shareholders when considering that his fund was largely made of liquidations, arbitrage plays, government securities, and convertible bond hedges; all of which would have generated either taxable income or short-term capital gains when they succeeded. In addition to these taxable events, the fund also had a rather high turnover ratio —again, looking at the strategies the fund employed, it’s not hard to see why. On top of all this, while Stahl does acknowledge that Graham’s investors would have still done markedly better than the indexes at the time, he had this to say about Graham’s returns from managing other peoples’ money (I assume in reference to the offsetting effect of management and performance fees vs the taxable events of a fund)…

However, there’s a very big difference between being a passive investor as a shareholder in such an enterprise and being the active investor. The common denominator between all of the great investment talents is that they weren’t merely able to earn a very high rate of return on their own capital; they were also able to mobilize the capital of others and earn a rate of return on that as well. That is why the whole field of free enterprise is not necessarily referred to as entrepreneurialism, but more properly as capitalism, because it embraces the mobilization of capital.

… Stahl has obviously taken his own advice here with his private Horizon Kinetics asset management business which collects fees on the various mutual funds, ETFs, and individual client accounts it runs14. (The public investment vehicle, FRMO Corp, can't really be compared, since Stahl and Bregman take no fees or other form of compensation other than their stake in the equity.15)

One of the final takeaways in the chapter is the taxation and opportunity costs of high portfolio turnover and selling too early that Graham and his shareholders incurred from the particular strategy employed during the life of the fund. Contrast this to the HK headline mutual fund, the Paradigm Fund, which I believe has had a historically low turnover ratio and which is currently 0.01% as I'm writing this16.

So after reading this chapter, the obvious question for an investor "betting on the jockey" Murray Stahl arises: HK or FRMO? IMO, FRMO is the better aligned option. Stahl has referenced FRMO as a “permanent capital vehicle”17 in older shareholder meetings and indeed shareholders can’t actually take capital out of the business like they could with a mutual fund or other structured product offered by Stahl’s HK asset management business. In addition, you’re not paying a management fee like you would be doing as a HK mutual fund or ETF shareholder —a fee which may offset management’s own invested capital from any taxation on distributions or turnover they may decide to exact on the fund. I've written a bit more about FRMO management's incentives in a previous post, here.

As a relevant aside on the subject of funds and alignment, I had asked about the INFL ETF in a past FRMO shareholder meeting and it was revealed that Jame Davolos —who manages the HK INFL Inflation Beneficiaries ETF— had ~25% of his liquid net worth invested in the ETF as of the time of the shareholder meeting.18

Here is Stahl in 2016 discussion the “permanent capital” design of FRMO:

In the FRMO shareholder letter, we discussed how we work to move away from the indexes in various ways. You might think of headings in that letter as divisions or business lines, but a better way to look at them is that they are doors that we can open or close when the opportunity set behind a particular door is rich. If it fails to be rich, we’ll close the door and do something else for a while. […] When Steve and I conceived of the idea of FRMO while we were sitting in a Burger King back in 1994, we wanted to design a company as a series of doors through which we could look for rich opportunity sets, and that’s where we would place our capital. […] But it requires patience, which brings us back to the way FRMO was structured. It was structured to be patient capital with which we are able to take the long view. It was to be permanent capital, so that we didn’t need to worry how the investments were marked to market month-to-month. You’ll see the same patient approach in our almost insignificant exposure to what’s called cryptocurrencies or digital currencies. —- https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2016_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

While looking at various references by FRMO’s S&B regarding permanent capital vehicles, I also found this bit which I thought was interesting as it also related to —not only Graham’s investing heir, Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway, but to— the previous chapter regarding Graham’s experiences during the great depression and the topic of exposure to left tail events:

Questioner: At any point in time would you or the management team every consider buying an insurance company to create a more permanent base of capital?

Stahl: Every time we talk about it among ourselves, Steve and I, we end up rejecting it. Here is why: because, even though we’d have a bigger permanent capital base, quicker than we otherwise would, the problem with it is we are exposed to the odd event. There is Hurricane Katrina or Hurricane Sandy or whatever other such event occurs; not that we have to be in catastrophe insurance; we can be in some other kind of insurance. But we don’t like the idea that, because of some three-sigma event, our shareholders’ equity could decline by a meaningful amount, and thereby disrupt our growth plans for years—because we would be, at least to the extent that would happen, drained of that much capital, and it might take years to replenish that. We just don’t like that. —- https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2014_Q3_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

Further related reading:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160703103351/http://www.horizonkinetics.com:80/docs/10-7-08%20The%20Asset%20Management%20Industry.pdf (see, “The Asset Management Industry”)

Original sources used in the book

(I will also add the posts associated with each chapter here as I complete them —as well as post for chapters where I may not have been able to find a source for the original essay online— in order to have a single place for everything; and to feel like I have a bit more flexibility to jump around between chapters.)

The Darkest Moments Of The Greatest Investors

“Benjamin Graham: Investor and Person”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191323/http://www.frmocorp.com/_content/essays/Benjamin%20Graham%20-%20Investor%20and%20Person%20-%20November%202008.pdf

(See above)

“Benjamin Graham Part II”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191337/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/Benjamin%20Graham%20Part%20II%20April%202010.pdf

(See above)

“John Maynard Keynes as Investor”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191350/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/John%20Maynard%20Keynes%20as%20Investor%20-%20October%202009.pdf

“John Maynard Keynes as Investor Part II”, https://web.archive.org/web/20160405144604/http://frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/John_Maynard_Keynes_Part2_October_2010.pdf

“Berkshire Hathaway, Part I”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191334/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/Berkshire%20Hathaway,%20Part%20I%20October%202008.pdf

“Berkshire Hathaway, Part II”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191339/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/Berkshire%20Hathaway,%20Part%20II%20October%202008.pdf

“Roger W. Babson Investor”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191408/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/Roger%20W.%20Babson%20-%20December%202009.pdf

How They Did It

“The Rothschilds — The battle of Waterloo”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191413/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/The%20Rothschilds%20April%202010.pdf

“The California Gold Rush — The Nature of Bubbles”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191345/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/California_Gold_Rush_and_Other_Bubbles.pdf

“Survivability Of Automobile Companies — How important is a company’s patriarch?”, (N/A)

“Cargill — A durable franchise”, https://web.archive.org/web/20160512141930/http://www.horizonkinetics.com:80/docs/ETF%20Compendium%20July%202010.pdf (pg.11)

“Charles Alfred Pillsbury — Making dough: Pillsbury’s unanticipated advantage”, (N/A)

“Jesse Livermore — Use of leverage”, (N/A)

“Eugene Meyer — On Top of a Mountain”, https://web.archive.org/web/20200927033458/https://horizonkinetics.com/top-of-mountain/

“Alfred Lee Loomis — The power of leverage”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714191304/http://frmocorp.com/_content/essays/Alfred%20Lee%20Loomis%20May%202010.pdf

“Charles Guth — The multiple bankruptcies of Pepsi-Cola”, (N/A)

“Otto Bettmann — Diversification and transactional mobility”, (N/A)

“Anheuser-Busch — Surviving Prohibition”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714155941/http://www.frmocorp.com:80/_content/essays/Anheuser_Busch_Surviving_Prohibition.pdf

“George Weidenfeld — Publishing Nazi memoirs”, (N/A)

“Piero Sraffa — Japan: Money good”, (N/A)

“Henry Luce — A picture is worth a thousand words”, (N/A)

“Lim Goh Tong — Empirical vs theoretical”, (N/A)

“Hong Kong Real Estate — Wealth creation”, (N/A)

“The Top-Heaviness Problem in Indexation”, https://web.archive.org/web/20150714125043/http://www.frmocorp.com/_content/essays/The%20Top-Heaviness%20Problem%20in%20Indexation%20and%20The%20Wealth%20Index%20May%202010.pdf

“Advertising Agencies — Valuing intellectual capital”, (N/A)

“Riches To Rags — Entrepreneurial vs professional management”, (N/A)

You can contact Horizon Kinetics themselves and ask for a copy if you’d like

Can’t find the exact interview where he mentions this, but will put the link here if I can find it later.

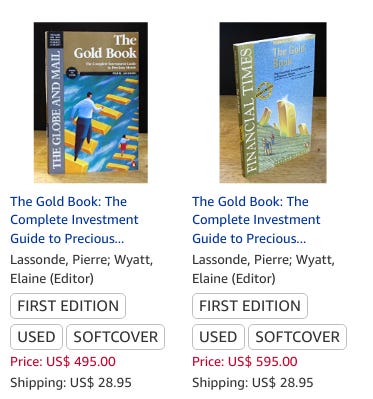

One such book that I can nearly guarantee is in Stahl’s collection is, Franco-Nevada founder, Pierre Lassonde’s “The Gold Book” whose latest 1996 edition trades for prices that may literally be worth more than its weight in gold (I just checked and my $35 1994 copy weighs 11.5 oz, so not quite).

I’d say that certain chapters of this book are written —to put it nicely— rather zen-like in that they teach, but do not instruct (thus my quote at the beginning of this post).

Also reminds me of this quote, sourced from Charlie Munger, used in a hypothetical conversation in Peter Bevelin’s “All I Want To Know Is Where I'm Going To Die So I'll Never Go There: Buffett & Munger – A Study in Simplicity and Uncommon, Common Sense”…

“And if you get into the mental habit of relating what you're reading to the basic...underlying ideas being demonstrated, you gradually accumulate some wisdom.”

BTW, you can read the whole book there for free on archive.org (and download a copy; you can check the virus scan of the PDF here) —rather than attempting to find a PDF copy from less reputable online sources or paying for one of the expensive, now out-of-print, used, analog editions…

UPDATE 20230223: Welp, not anymore, I guess. Looks like someone spilled the beans (hopefully not me) and the wrong person found out and had it removed from archive.org. I suppose this is a good reminder that there are limits to how much alpha should be openly shared.

It appears to be alluded to in the forward to the memoirs that Graham’s “margin of safety” strategy came into formation only after being humbled by the Great Depression. I will note that Graham did not begin working on “Security Analysis” until well within the midst of the Great Depression, not before (though his idea for the book was originated “in the lush times of 1927”).

I thought this was interesting, re. cost structure of asset management: https://caia.org/sites/default/files/understanding_the_cost_of_investment_management.pdf

In any case, FRMO’s COGS are nonexistent and opex which is mostly auditing, accounting, OTC Markets’ listing and services fees, and their power usage for their crypto mining operations are all well covered by FRMO’s dividend income (from their TPL position) + fees (from FRMO’s “Participation in Horizon Kinetics LLC Revenue Stream”). The remaining bulk of FRMO’s “revenue” is unrealized gains in equity securities that Stahl then just gets to build for free with the real revenue that’s left over.

I ask about the fluctuations in FRMO’s opex, here: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4570490-frmo-corporation-frmo-q2-2023-earnings-call-transcript (1:00:25)

https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2022_Q3_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

Let me answer the last portion of the question. The primary manager of the fund gave me permission to inform you all that over a quarter of his liquid net worth is in the fund and he buys more each quarter.