Notes on "How They Did It": John Maynard Keynes 2

Leverage as an asset class (and how to lever up without going broke)

This is a continuation of a series of posts covering the various chapters of Murray Stahl’s 2011 hardcover-only book, “How They Did It”, for the purpose of making the content digitally available in some approximated form, mostly for my own future reference. For more background on what I’m even talking about, how this is series is formatted, and a complete list of the original sources compiled in the book, see the post here:

Keynes Part 2: Leverage as an asset class (and how to lever up without going broke)

“[…] so I bought the building, I repainted the units, I bought new furniture, I doubled the rents, and all of a sudden I discovered that I had a significant cash flowing asset; and obviously among other things what I learned from that was that the merits of cash flowing assets is the only kind of thing that matters. I mean you can't pay your rent or you can't pay your interest payments with earnings you can only pay it with cash.” —- Sam Zell

“[As] someone who started out with nothing and was capable of building a fortune, particularly one that wasn't predicated on some invention or something that created massive multiples of the original idea, somebody who operated like that needless to say had to —in order to succeed at that level— you had to undertake serious leverage. So for the first 25 or 30 years of my career we were always over leveraged we were always literally living hand to mouth despite the fact that we were very successful; nobody's lifestyle reflected that because there was never any cash and then in various downturns obviously our mettle was tested and what we learned was that… I had an experience and I think was 1992 where according to Forbes magazine I had a net worth of a billion dollars and it was a Wednesday and I was worried about how to make payroll on Friday; so I learned that yeah I had a lot of assets but to the extent those assets weren't liquid I didn't have any value so that's where that phrase [“liquidity equals value”] comes from” —- Sam Zell

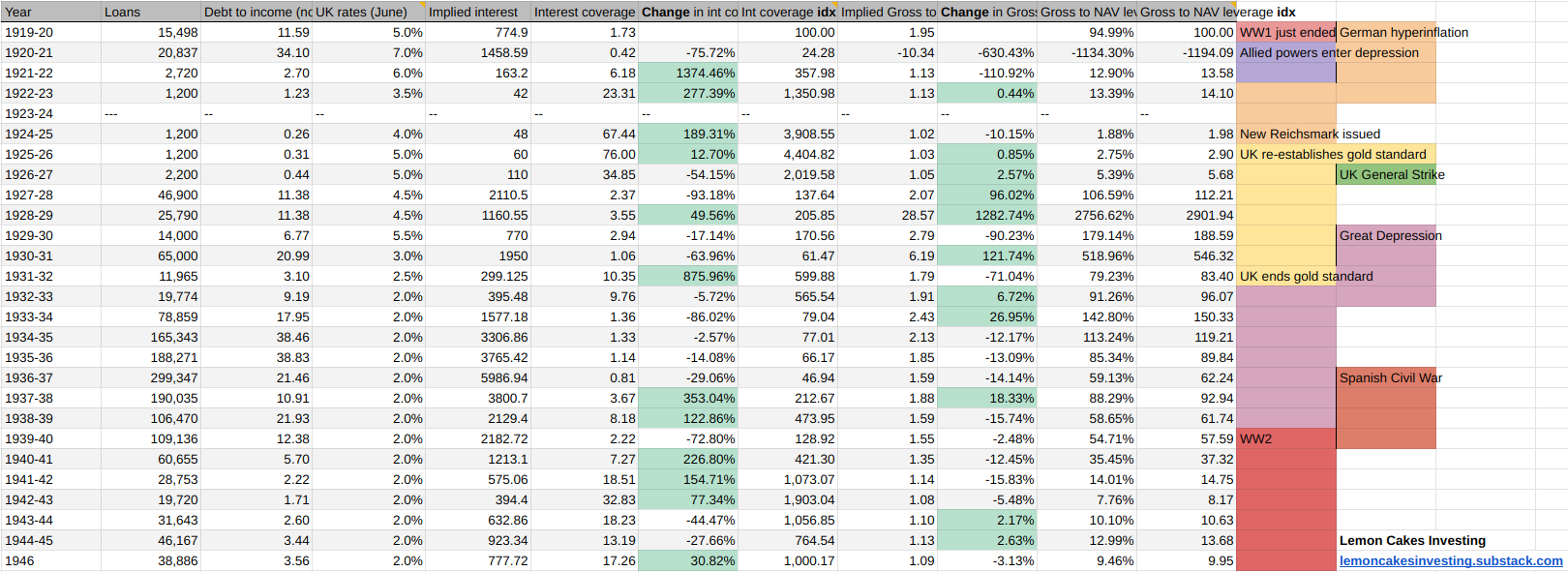

Like Graham’s use of comparatively cheap leverage during the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes also employed significant leverage during times of high economic uncertainty throughout his investing career (which included during the midst of the Great Depression). Working with the table in the corresponding Stahl essay, sourced from Moggridge, Donald E., ed. “The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes”, we see an average implied gross leverage ratio of 130% for Keynes’ portfolio (and in no year was he ever not levered to some degree) —I believe these figures are not from Keyne’s management of the King’s College Chest Fund, but from his own personal investment portfolio (which he also used for personal spending).

Here we can see gross leverage (log scaled due to positive skew) next to the Chest Fund index performance and UK stock market over the years, starting in 1927, for a reference proxy of Keynes’ general investing performance across his periods of leverage.

In the essay, Stahl notes that during the 1930s —when Keynes transitioned to a long-term investor (as mentioned in the previous post on Keynes)— as the cost of debt was drastically reduced in response to the Great Depression, Keynes maintained an “ever-rising margin of safety in terms of the cash-carry of his positions. Perhaps because of that reason, he was able to be a long-term investor.”

Like how Graham similarly took advantage of cheap debt during the Great Depression by leveraging on (by that time, cheap) high quality preferred equities: when available portfolio income yield (z) was greater than interest cost of debt (r), that basis point spread could be captured by taking on leverage to produce a higher target yield (x), and that captured spread can then be used for re-investing/leveraging or paying down debt, thus gradually increasing your economic interest / net assets and the absolute dollar amount of your income yield as the underlying capital base grows.

(Really, I just wanted to try Substack’s new LaTex editor here; turns out it can’t do \newline commands, so that sucks)

Stahl speculates that this is what Keynes was taking advantage of during the Great Depression based on looking at how Keynes’ NAV increases after spikes in debt during this period. We can kinda see this playing out by graphing Keynes’ debt and interest coverage over time:

Using the data from the table “Keynes's income (£) by tax years, 6 April 1908 to 5 April 1946” provided in the essay and referencing his loan amounts against the history of UK base rates1, we can see (above) that Keynes’ leverage would have periods of spikes, where interest coverage of total debt then logically falls, followed by his interest coverage maintaining or rising again as leverage falls —as the debt was presumably put towards investing in cash-flowing securities that added to Keynes' income and were used to then pay down the loans; (after his heart attack in 1937, we can see his leverage tapering off as his interest coverage was allowed to grow until his eventual death).

Stahl comments that Keynes understood that “leverage is an asset class that can be defined. It has precise numerical properties, unlike modern-day asset class nomenclature, like emerging markets and small capitalization stocks, which have ambiguous characteristics.”2

Stahl’s kind of leverage (how to lever up without going broke)

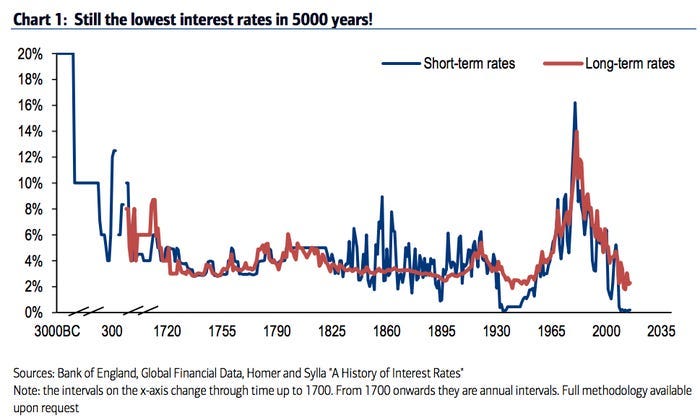

I find all of this talk of leverage curious —and there are several more chapters on this topic in the book where Stahl brings this topic up— given that I could not find much evidence of his public FRMO vehicle ever employing much leverage itself throughout it’s overlapping decade of coexistence with the lowest interest rates in decades starting in 2008…

… I suppose, that is, unless you consider the operational leverage of Stahl’s private Horizon Kinetics asset management business:

Asset management is a business characterized by remarkable operating leverage. As every asset manager knows, when the assets under management increase, the costs don’t necessarily rise commensurately, and the earnings advance at an unusually high rate. Of course, when the value of the assets decline, it is accelerated by the departure of large numbers of clients, and it’s very difficult to adopt any countervailing cost containment moves. —- https://web.archive.org/web/20160703103351/http://www.horizonkinetics.com:80/docs/10-7-08%20The%20Asset%20Management%20Industry.pdf (see “The Asset Management Industry”)

Perhaps operating leverage (measured relative to fixed costs) is a preferable type of gearing risk to take on vs financial leverage (measured relative to interest expenses)3 when the idea is combined with Stahl’s thoughts on royalty-like businesses, “dormant assets”, and scalability —which will be touched on a bit in later chapters— which may have more variable income, but consistently low and stable fixed costs; and with the cost of debt having recently risen the fastest it ever has in decades4, relying on embedded operating leverage vs debt or margin seems like an increasingly attractive option.

From Stahl himself on —his present POV regarding— leverage vs “asset-light, hard-asset” businesses (and an argument for why such assets are likely to remain attractive into the future):

The challenge to asset allocators and other investors is that an insufficient number of such hard asset companies exist to form an index. Also, the aggregate market capitalization is very small in relation to the great amount of assets in the world that require some inflation protection. [In lieu of the availability of “asset-light, hard-asset” investments] many investors in the practical world, therefore, are compelled to use leverage as an inflation hedge, on the premise that the cost of debt capital is low and, in any case, even modest inflation will eventually erode the purchasing power of the obligations that must one day be repaid. That is, for investors employing leverage, paying back ‘in cheaper money’: the amount of the bond or loan due on the maturity date in five years or 10 remains the same as on the first day of the loan, but the nominal income of the borrower has presumably inflated over time.

[…] In any case, it is obvious that Keynes frequently made use of enormous leverage relative to his net assets. This process has continued among investors and business people to this day. The contemporary world might be the most leveraged society in history. That means that the constituency supporting debasement of debt and money is very large. —- https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/InflationandEconomicThought_Nov2020.pdf

… this operational leverage, hard-asset mentality is also extended to exchanges by HK

As bad as that scenario might be for a bank, it’s great for a securities exchange, because exchanges are where people go to hedge risk. Redefining a securities exchange as an asset-light croupier – that has information content. The croupier class of business organizes a venue, with little capital at risk, that facilitates transactions. —- https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q3-2022-Review-1.pdf

(This idea of the “croupier” business as a transactor of hedges as society and risk management complexity expands infinitely has popped up in several other past HK writings and you can read more about it in the footnotes)5

Here’s Stahl answering a question regarding a question on the upside of Texas Pacific Land Corporation (TPL) (the largest investment of FRMO and any of Stahl’s HK entities, collectively owning 20% of the 880,000 acre business) in 2020…

Moderator: And then on TPL, this is the kind of favorite question that everybody asks. Can you speak a little bit more about the potential upside in cash flow for TPL, both on the base-case and best-case scenarios?

Murray Stahl: […] So, the operating leverage – not the financial leverage, because there is no debt – is just extraordinary. Also, the earnings are – not entirely but, more or less, it’s true to say this – are essentially free cash flow. There are very few companies like that. That’s about the best I can say about the TPL earnings case without getting myself in trouble.

My thought is that —despite talking excessively about “leverage” in the book, while appearing to take none on in his actual investing activities— Stahl is simply choosing operational leverage (specifically, the kind of operating leverage that he refers to as “optionality”)6 over financial leverage with a focus on buying “asset-light, hard-asset” businesses and exchanges (you could call it ‘asset-light, intellectual-capital-assets’ businesses) as a way to access some form of gearing on investments without risking total destruction. Note that, given his large position in TPL and (after a 2019 proxy fight)7 position on the board of directors, Stahl also appears to be gearing on the idea of “leverage” as described by Y Combinator founder Paul Graham...

To get rich you need to get yourself in a situation with two things, measurement and leverage. You need to be in a position where your performance can be measured, or there is no way to get paid more by doing more. And you have to have leverage, in the sense that the decisions you make have a big effect. —- http://www.paulgraham.com/wealth.html#:~:text=slows%20you%20down.-,Measurement%20and%20Leverage,-To%20get%20rich

More generally, I’d call the approach ‘high-operating-leverage, low-adjusted-fix-costs businesses with perpetual call options on growth and innovation in the business and its downstream markets (this low-fixed-cost idea factors in R&D and SG&A expenses as well, per the work by Michael Mauboussin on accounting for intangible assets and intellectual capital)8.

“For example, if you look at some of the investments we have, it wasn’t that many years ago it was considered to be an impossibility to extract anything from some of the properties or royalty interests they held. Just physically impossible. We believed that, but we didn’t believe it was going to be a permanent condition. We thought that one day someone was going to figure something out. […] We have a call option, effectively at the money, on every one of them. We don’t hold any patents, but we effectively have a call option on everything. If people realized how valuable that is, all these hard asset companies would trade at radically different prices. Maybe it’s a good thing that investors don’t realize what the optionality really is. Imagine if there were such a thing that you could buy an option on a patent, or a set of patents, or an infinite number of patents, even ones that haven’t been patented yet, and which go on forever. That would be worth a lot of money.” —- Murray Stahl

From this POV, you want businesses that are not often subject to change and have long product life-cycles themselves, while also having characteristics such they benefit from more change/competition in their downstream markets. Imagine setting a entanglement net between the shore and a sturdy rock in the middle of a river, the more shifting and moving the river, the more you can catch without much work as the current does the trawling for you, but the dynamics of the rock and the net themselves aren't really subject to much change in kind —that net is a durable call option on the river activity.

“Disney is an amazing example of autocatalysis … They had those movies in the can. They owned the copyright. And just as Coke could prosper when refrigeration came, when the videocassette was invented, Disney didn’t have to invent anything or do anything except take the thing out of the can and stick it on the cassette. […] [I]t’s a marvellous model if you can find it. You don’t have to invent anything. All you have to do is to sit there while world carries you forward.” —- Charlie Munger, https://robdkelly.com/autocatalysis-in-business/; https://jimbouman.com/poor-charlies-almanack-charlie-munger/

In terms of bonds, it’s like buying a short/medium-term 3-5yr bond with generally predictable payments (the operating business) that, on the other side of that same piece of paper, has a, say, 10-30yr (and thus longer-duration) bond printed on it with an uncertain and (somewhat random) variable payment schedule (the dormant opportunity call option). What you want to find are situations where —due to other people’s shorter time horizons, inattention, pessimism, or structural barriers to capital— Mr.Market (perhaps not even checking the other side of the paper) is offering you these two-sided bonds based only on considering the value of the lesser-duration side, greatly discounting (or totally ignoring) the value of the longer-term component and giving you the chance to pay fair value for just the value of the short-duration side of the asset.

A good example of this can be found in a 2018 Value Investor Insight interview with Stahl where he is asked about his TPL position —HK’s largest holding, being the largest shareholder themselves, having invested very early on in the business— which has since gone on to become a 100-bagger (actually, a 600-bagger) for Stahl:

The governing document requires any income earned from things like easement fees, grazing fees, oil, gas and mining royalties, or periodic land sales to be applied to the repurchase of shares and to pay dividends. When we first bought into this in 1995, we basically signed on for a 5% or so return from stock buybacks and the dividend, with pretty much infinite call options on what they could make happen with the land. Maybe people wanted to develop it. Maybe there was oil there that could one day be economically extracted. We didn’t really know, but we liked the potential odds. What’s changed is that some of the options went heavily into the money. A lot of hydrocarbons have been found in their areas of Texas, including the Permian Basin, and technology improvements mean these reserves can be exploited for decades.

Both types of leverage increase revenue-to-FCFE sensitivity, but you have a harder time going broke with asset-light, operationally leveraged businesses when things don’t go as planned vs the higher solvency risk and necessity/temptation to divest valuable assets in bad times for a financially leveraged operation —kinda wish someone had told this to Blackstone Mineral’s CEO in 2020 before they sold of valuable Permian acreage9 and bought into increased hedges in the market panic only to see the rapid gains in oil prices the very next year.

In Stahl's own words10 on the subject of the low invested-capital requirements of small exchanges in which FRMO was buying private equity stakes in 2014 (which have at this point mostly been rolled into11 their MIAX investment)...

Another is that not very many days ago, we announced that we took a big interest in the Bermuda Stock Exchange. […] Someone once asked me, “What is the point of going after ‘the peewee exchanges’?” My answer is that if you create something, the return you get, to some degree, is a function of the denominator, in other words, how much money you need to invest in it. As to the numerator, the product is going to do whatever it is going to do; it would do the same thing if it were part of a bigger exchange. However, if the denominator is small enough—the idea is to get the maximum operating leverage by having the minimal investment necessary to secure a place in that instrumentality. […] There will be a diversity of investments, and they’ll have the common theme of an idea. Intellectual capital, given the scale of investment, can have a lot of operational gearing.

From an investor POV, looking for going-concern call-options may be a safer way of obtaining leverage without taking on margin12. You're basically buying at-the-money LEAPS13 with no time decay and no set expiry date, while you wait for the underlying business to pay off in the long-run, mainly by the merits of it's undeveloped assets (and, unlike actual LEAPS, you actually get to collect the dividends of the already-developed assets of the underlying in the meantime).

Franco-Nevada founder Pierre Lassonde has mentioned14 that, in the initial periods of building the company and acquiring royalties, they were always able to outbid competitors because no one was valuing the embedded optionality of the properties, so FNV could model a value for that hidden element and make bids above the DCFs applied to the existing business that others were basing their bids on —by the way, the interview was in late 2022 and Lassonde claims that this discounting is still happening the royalty space to this day (Mauboussin's latest "Expectations Investing" contains a chapter on reasoning about and valuing real options for those interested in investigating these claims)15. I believe that this is the kind of leverage that Stahl is going for in his investments.

A large portion of Stahl’s investments —from royalty businesses like Texas Pacific Land and Franco-Nevada, spread-capturing businesses like security exchanges, to other “dormant assets” like Bitcoin and Diamond Standard— are characterized by scalability combined with low overall costs and high operating leverage (as well as high barriers to entry and low incumbent rivalry by the simple fact of their natural scarcity the geologically fixed nature of the assets). Note also that the operating leverage of these businesses grows organically; that is, without necessarily being dependent on the timing and debt-management acumen of management (unlike with financial leverage) in proportion to the economic, on-the-ground demand for the business. For example, security exchanges make more money for no added capex as market participants on the ground trade more volumes or build demand for new securities to trade (via new company IPOs, securitization of new asset classes, or new formulas for derivatives contracts), mineral royalties make more money at no added cost when the price of oil rises or extraction technologies improve, and land/surface royalties and leasing/development operations just sit there and generate profits when demand / use cases emerge for its development (eg. housing, electric grid infrastructure, freight transportation, etc)...

“When Judas betrayed Jesus Christ for thirty pieces of silver, these shekels would have been the equivalent of two and a quarter ounces of gold. In today’s values, Judas sold Jesus for about U.S.$900. It was a significant sum of money and the Bible tells us Judas ‘bought a field with the reward of his wickedness.’ It doesn’t mention the field’s size but any purchase of land was a major transaction. You couldn’t buy a field for $900 today, which may mean land is a better hedge against inflation than gold.” —- Pierre Lassonde, “The Gold Book” (1994)

I also wonder if perhaps the underlying leverage you get from investing in a financially leveraged business is normally already priced into the stock (thus offsetting any excess returns from positive movements)16 vs a stock whose leverage comes from its operational gearing —which in the process of writing out this post, I’ve found to be a much less readily available metric.

Meanwhile, earnings volatility that may come from operational leverage is of little concern given proper diversification and relying on the power series of outperformers and low turnover. As we saw in the previous post on Keynes re. his art collection, diversification and letting Pareto distributions work themselves out can be an index-smashing strategy in the long-run, even if your selection taste is “lamentable” —which I think Stahl’s is certainly not.

“… they’d say, “What about the risk, it's so volatile, right?” But they didn't have the concept of how to handle the risk of something so volatile. If you don't realize or think that the gearing, the return leverage, is on an orders-of-magnitude scale, you don't realize that it's quite possible to buy some de minimis amount—by de minimis, meaning it wouldn't affect you in the slightest if it goes to zero—and yet, if it somehow does work out, it would be an amount that could radically change for the better your financial life forever.” —- HK co-founder, Steve Bregman

Further reading:

https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/InflationandEconomicThought_Nov2020.pdf

https://www.maynardkeynes.org/keynes-career-timeline.html (Didn’t really have any specific place to cite this, but I relied on it for a lot of stuff here, so wanted to include it somewhere)

You can actually read Stahl expounding a bit on this latter idea of the muddling of investment thought due to the way language is used in the field, here:

… may he never read my writings.

https://www.wallstreetmojo.com/operating-leverage-vs-financial-leverage/

https://www.westga.edu/~bquest/1998/leverage.html

https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/operating-leverage/

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/degreeofoperatingleverage.asp

https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/accounting/leverage-ratios/

https://web.archive.org/web/20150506062559/http://www.horizonkinetics.com/docs/10-7-08%20Observations%20on%20Securities%20Exchanges.pdf (see “Observations on Securities Exchanges”)

https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2018_Q1_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

This should give you a sense of the operating leverage of this business. Sometimes we don’t call it operating leverage; we call it optionality. Now you understand how powerful it really is. And that’s just one vector. We want as many vectors as possible, and we want them to be differentiated. In the fullness of time, if we have enough of them, there will always be at least one or two that are working.

You can find more example of this idea yourself using the google search query:

(site:frmocorp.com | site:horizonkinetics.com) + ("operating leverage" | "operational leverage" | "optionality")I use the qualifier of “adjusted” because some tech companies would seem to fit the bill of this category until you consider the various intellectual capital adjustments —such as the portions of R&D and SG&A that should be considered a form of maintenance capex (rather than opex) for these businesses— that should be made when considering the total invested capital and the ROIC thereof.

Michael Mauboussin has written about making adjustments for intellectual capital and intangible assets in various forms; the appendix here (https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_intangiblesandearnings_us.pdf) gives some useful hard suggested numbers.

“Pierre Lassonde Reflects on his Life, Career, and Paving the Path for Mining's Royalty Business”

https://www.expectationsinvesting.com/online-tutorial-10

Of course, FNV is also always out there buying up royalties using the logic as their founder Lassonde described; my understanding is that it’s not very often a small royalty operation makes it the the public market before one of the larger operations like Franco-Nevada or Royal Gold buys them out.