This is a continuation of a series of posts covering the various chapters of Murray Stahl’s 2011 hardcover-only book, “How They Did It”, for the purpose of making the content digitally available in some approximated form, mostly for my own future reference. For more background on what I’m even talking about, how this is series is formatted, and a complete list of the original sources compiled in the book, see the post here:

Berkshire Hathaway: Doubting Buffett before the fame… and even for a time after

Today, Warren Buffett is solidly an investing icon with dozens of books written about him that are read by thousands of investors around the world and with a not-insignificant fraction of those readers flocking to Omaha, Nebraska each year to hear him speak in person.

However, throughout the tumultuous period of the 1970s, Stahl in this chapter comments on how despite a continually growing book value within (the relatively unknown at the time) Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, on the outside, the stock’s price told a very different story. I think these two tables from the essay are illustrative enough…

At the end of 1975 our insurance subsidiaries held common equities with a market value exactly equal to cost of $39.3 million. At the end of 1978 this position had been increased to equities (including a convertible preferred) with a cost of $129.1 million and a market value of $216.5 million. During the intervening three years we also had realized pre‐tax gains from common equities of approximately $24.7 million. Therefore, our overall unrealized and realized pre‐tax gains in equities for the three year period came to approximately $112 million. During this same interval the Dow‐Jones Industrial Average declined from 852 to 805. It was a marvelous period for the value‐oriented equity buyer. —- Warren Buffett, “1978 Letter To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.”

In nearly every year throughout that decade, BRK traded at a discount to —its continually growing— book value. During this same period, Buffett would also increase his stake in the business by around 100% of his existing interest. It could be understandable that investors did not recognize this opportunity at the time as Buffett was still relatively unknown during the 1970s, but this would be a harder case to argue during the 1999-2000 dot-com bubble that saw the market again price BRK at a significant discount to NAV; my understanding is that Buffett had by this time become a house-hold investing and business name during his take-over of Salomon Brothers in 19911, by which point Buffett was in his early/mid 60s —of course, this incident did not necessarily paint Buffett in the most flattering light.

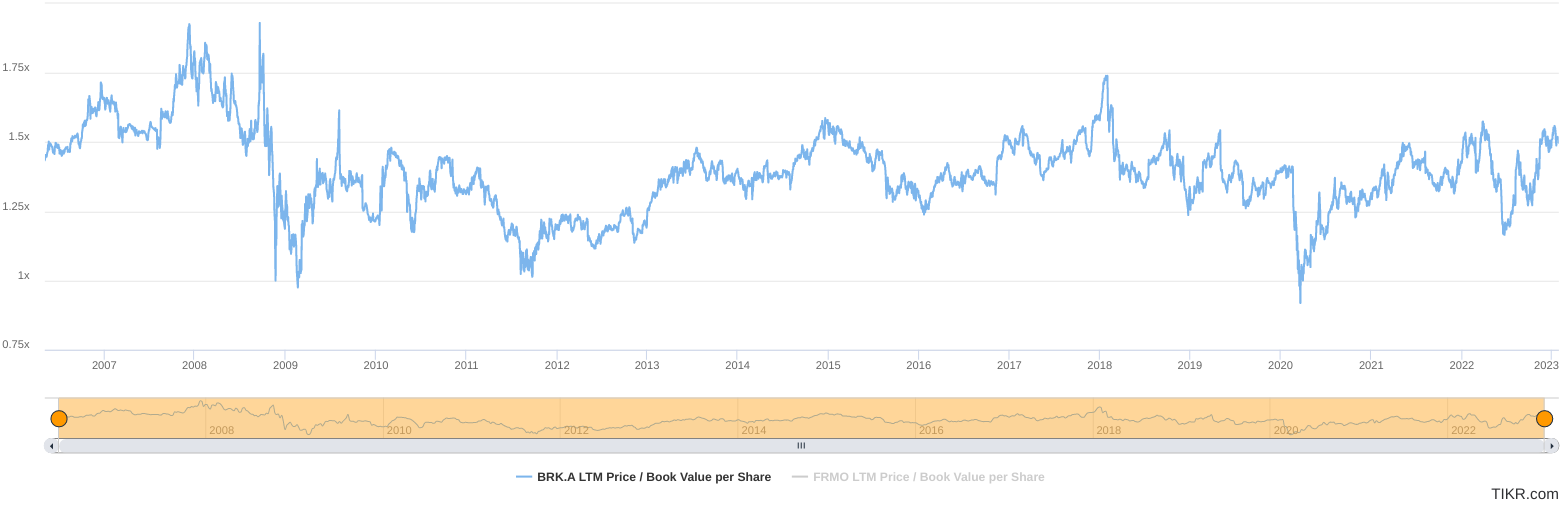

We can see that, since that time, BRK has never traded at any discount to book comparable to those other periods, save for a few trading days in 2008 and 2020.

Below, we can see BRK's P/B compared next to FRMO’s historical P/B. Note that 1. while it tends to trade at seemingly large book multiples, there are a lot of assets on FRMO’s balance sheet that are held at-cost or at somewhat arbitrary values (for example their Horizon Kinetics revenue royalty stream) and 2. FRMO is currently trading near it historical low-end; of course this last point is lucrative only if the main FRMO investment theses are correct or not…

For FRMO’s pre-2012 periods (including 2008-2009) not recorded in TIKR, these values were self-reported in the FRMO 2011 shareholder letter here. I’ve added the P/TBV values using approximate stock prices around the same day the letter was published…

… Again, as I write this, FRMO is currently trading at a P/B of 1.50x; lower than in 2010 and comparable to the tail-end of March 2020 and is now derisked of it’s large GBTC position (by way of unrealized losses from the ‘crypto winter’ of 2022) which now makes up just 3% of FRMO’s TBV2 (FRMO started with just a 500bps allocation back in 2016). It should also be noted that during this whole time period of available nominal P/B data for FRMO, interest rates were largely zero-bound, so historical comps may not be the best gauge of opportunity here; though I do personally think that FRMO is trading much closer to parity with its true book value than what is reported.

Stahl remarks that while much has been written attempting to extract how Buffett identified his investment opportunities (in a similar manner to the investment community’s treatment of Ben Graham), much less time is spent on understanding the conditions of extreme investor pessimism that created those opportunities —recall the first post in this series on how the Great Depression played a large role in making Ben Graham’s outstanding track record possible.

This is perhaps an error, in the sustained panic of uncertain times, of ignoring, forgetting, or mis-analyzing what characteristics of a business are Lindy or perhaps illustrates the difficulty of analyzing and pricing-in the durability or value of the intellectual capital that Buffett brought to BRK; both of these concepts are explored to a certain degree in later chapters.

[M]any entrepreneurs focus only on short-term growth. They have an excuse: growth is easy to measure, but durability isn’t. Those who succumb to measurement mania obsess about weekly active user statistics, monthly revenue targets, and quarterly earnings reports. However, you can hit those numbers and still overlook deeper, harder-to-measure problems that threaten the durability of your business. —- Peter Thiel, “Zero To One”

Further related reading:

Poor price performance affords greater wealth accumulation… iff you’re running a permanent capital vehicle

“People who play it too safe take the greatest risks, did you know that? In the long haul, the intelligent risk takers developed the greatest security. [It] is the wise person who learns the importance of risk taking” —- Earl Nightingale

“When we brought in the most amount of our stock was in ‘74, ‘75, and so on. That was a very good time to be buying. That was the worst crunch in 50 years. We were very lucky to have cash on hand at that time. Most people, they don’t have tons of money to invest in the bottom of these booms. We’re all in on them. We’ve been in them for a long time. We just ride it out.” —- Charlie Munger

The following chapter of the book relating to Buffett is highly related to the previous in that it continues to explore how the severe market pessimism of the 1970s, that Berkshire was caught up in, created seemingly irrational discounts, but also looks at how the structure of Berkshire Hathaway —being a permanent capital vehicle rather than a proper fund with a fluctuating share count— allowed for Buffett to capture a larger proportional economic interest in the same growing business while it was being shunned by the market at large.

The relation back to Stahl’s own permanent capital vehicle FRMO should be fairly plain and I won’t belabor that point as it is already covered in the first post in this series on Ben Graham. However, I am currently working on writing some thoughts around a similar situation that exists today which parallels Buffett’s exploitation of market pessimism around a permanent capital vehicle he controlled —which is the topic of this section— which I will be finishing some time after this post.

In the corresponding essay, Stahl presents an interesting rationalization for why investors may have discounted Berkshire so heavily. BRK shares prices traded all the way down to a ~50% discount-to-book around 1974 to 1975. At the time, BRK had an earnings yielded3 of just 5.5% relative to its nominal book vs the 8% interest on the 10yr UST at that same time4. The 50% discount applied by the market to BRK's BV in the 1970s makes sense from a ‘yield-on-book’ POV wherein it could be argued that, by discounting the book value nearly 50%, it created a real earnings yield on the (discounted) book value of around 10%. This approximated the actual yield that was available from USTs as rates were raised by Burns and then Volcker to fight inflation during that decade (plus a few extra pps as an equity premium yield requirement). Of course, this also discounted BRK’s ability to continue to grow book value (which as we saw in the previous section was indeed happening during even the worst years for the broader market), and generate increased earning on those business holdings in the long run. Basically no one was interested in alternative long-duration assets which, to be honest, kinda makes sense given that the 10yr UST yield would go on to reach 15% by late 1981; it’s just that BRK would go on to beat this (and outlast the maturity terms) by returning a 30% CAGR from 1980 to 20005 (and a 19% CAGR from that same period up to today).

This is similar to discounting the par value of a X%-yielding bond to raise the yield such that it is commensurate to a newly issued (X% <) Y%-yielding version of the bond when rates rise, in addition to some added risk premium on the older X%-yielding bond.

While I'm not sure that it would totally make sense to try to calculate this for FRMO using their nominal income statement reports given that accrual accounting records unrealized investment gains/losses as income6, from this perspective of trying to determine some kind of earnings yield on book, we can use FRMO's the LTM net change in cash (since 1. their revenue figures include unrealized gains/losses from investments and 2. their operating cashflows do not cover the various investing and financing activities) to see that the business currently trades at a 1.7% cashflow/TBV7 as of my writing this vs the 4% market yield on the 10yr UST and effective Federal Funds rate of 4.5%8 (and I think that FRMO's nominal book value is actually understated to it's actual value as well, bringing FRMO's yield even lower)...

********** UPDATE 20230815:

Using the numbers from the recently published 2023 annual report (FRMO’s fiscal year ends in May), the cashflow-to-TBV yield is now 2.75%. FRMO would need to trade at a ~43% discount to TBV in order to have a cashflow yield on book comparable to the current EFFR of ~5%; my emoji statement below this update still stands.

There are certain adjustment I’m OK with that could be made, such as removing crypto assets from the TBV (since these are not intended by management to be USD-generating assets, but rather accumulated for their prospective value themselves) and using the Fed rate futures dot plots (averaging the median rate targets for the next 3yrs + longer run) to get a CFFO/(USD)TBV of 3% vs a longrun Fed aggregate rate of 3.97%, which closes the spread to a degree.

**********

Not totally sure what to make of this at the moment; I recently listened to an NPR interview where they were talking to a wine taster who was rated wines online using strings of emojis rather then commentary9 and the rating I’d give to FRMO’s below-FFR yield-on-book would be... 😅✂️🧐.

For businesses other than investment vehicles and holdCos like FRMO, book value might not matter as much and if you wanted parity with a future of 8% short-term interest rates —and who knows, maybe we'll revisit those 70s-era rates by 2024 given how things have played out over the past year— you'd want to buy stocks with durable FCF and whose fair value you believed priced the stock at or below (1/0.08=)12.5x that FCF (an 8% FCF yield) —maybe make it an even 10x P/FCF as an equity risk premium vs USTs.

In any case, having a permanent capital structure allowed Buffett to accumulate a greater share of BRK's sustained/growing pie at a discount to NAV (vs a shrinking pie at a proportionally shrinking value as would have been the case with share redemptions at a mutual fund or ETF during this same period of market pessimism). Throughout the 1970s, the market generally traded at a Shiller P/E well below it’s long-term 15x average…

… The bargain environment during that time is also reflected in the Wilshire/GDP ratio (AKA the “Buffett Indicator”10).

This particular broad-market valuation measurement was also mentioned in the recent 4Q2022 HK Commentary —now in stark contrast to the levels it was at during Buffett's time in obscurity— where Steve Bregman notes that...

“Much debate about whether the market is cheap enough to now be rewarding, or just fairly priced, or maybe not. […] The comprehensive version of the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 is to compare the market value of all publicly traded stocks to GDP. It dispenses with all the underlying judgments and complexities about whether and how to make adjustments for companies that might have negative earnings, what to do about noncash write-downs, etc., etc. It simply relates the market value that investors have jointly assigned to the entirety of public corporate earnings and/or book value and/or intangibles to the economy in which they operate. That valuation multiple remains at the highest level in 50 years, other than last year, of course.”

(This perhaps explains FRMO’s consistently large cash position11, though I wonder how expensive this index would look vs historical levels if the FAANG stocks —which HK has much bemoaned as dragging up the rest of the market and warping perspectives (and make up a large part of the Wilshire index)12— were removed.)

Had BRK been a mutual fund during this time of investor pessimism in the 70s, rather than the permanent capital vehicle that it was, there would be no NAV discount at all; the capital would simply flow out in real terms by way of redemptions as investors pulled their money out of “the Berkshire fund”, which would also have impacted Buffett's ability to continue to use the “fund’s” investment income to opportunistically buy back BRK stock at a NAV discount or invest in equities at valuations that (as can be seen above) were to be the lowest he’d see for the rest of his investing career —even up to the day that I’m writing this.

Also of note, real estate billionaire Sam Zell was also making hay during the market pessimism of the 1970s:13

Following a market crash in 1973, Zell spent the next three years acquiring $3 billion in real estate assets, much of it for $1 down. He built the portfolio by going to lenders and offering to take future operating losses off their hands in return for equity. Zell was able to carry the properties long enough for them to return to — and exceed –prior valuations. “As it turns out, we made a fortune,” he said.

… As well as investor John Templeton. Templeton (who was also featured in William Green’s “Richer, Wiser, Happier”, which I recommend) is also mentioned in a 2021 HK Commentary where his disciplined, (thematically) concentrated, and contrarian style was shown to hold up against the market through the 1970s and beyond:

Further reading:

http://www.austinvaluecapital.com/resources.html; contains a downloadable PDF compiling everything written by Buffett starting from 1957 to June 2021.

https://archive.nytimes.com/dealbook.nytimes.com/2008/09/24/warren-buffett-and-the-salomon-saga/

https://theconservativeincomeinvestor.com/the-moment-warren-buffett-became-famous/

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/moment-america-met-warren-buffett-115906138.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salomon_Brothers#1990s_treasury_bonds_crisis

Based on the Q3FY2022 conference call where Stahl states that FRMO held 588,796 shares of GBTC directly and indirectly at that time.

The essay does not actually specify earnings vs, say, FCF or some other metric, but I assume it’s earnings here.

Using the BRK.A marketcap data here: https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/BRK.A/berkshire-hathaway/stock-price-history

($56400MM÷$270MM)^(1÷(2000−1980))−1 = 0.3062

The bulk of FRMO’s “earnings” or “net income” is actually “unrealized gains in equity securities” and FRMO’s main assets are its securities holdings, so the better description would be to call the LTM NI/TBV figure something like ‘net annual additional equity yield on existing equity.’ With this in mind, FRMO has a 20% LTM NI/TBV.

We could also just take the “fees” (made up of HK advisory fees and the HK revenue stream ownership) and “dividends and interest income” from the 2022 income statement, minus opex, and divide by TBV (“attributable to shareholders” in the balance sheet) and get a 2.7% yield on book —slightly higher than the FCF/TBV number.

https://www.wallstreetmojo.com/unrealized-gains-losses/#h-unrealized-gains-and-losses-accounting

$(−0.46MM + 2.73MM + 0.08MM + 0.88MM) / $189.32MM

Though I’d also note that mid/smallcap stocks are currently trading around the cheapest valuations they’ve been at since the 2020 March COVID shock and the 2008 GCF.

https://www.morningstar.com/articles/1128280/small-cap-stocks-are-really-cheap