Cash ($): Hike the FFR, save supply chains (and the world)?

The lowest duration, highest liquidity bond around -- and maybe (eventually) quite high yielding as well

“The financial system nowadays is very fragile […] I think Jeremy Grantham1 will prove to be correct that over the next 10 years if you don't lose any money you're actually doing quite well [Interviewer:] Yeah I've heard the term you should plan on losing money in the coming environment your strategy is just to try to lose less than everybody else does and be a relative winner.”, Marc Faber

With current mainstream attention finally now focused on inflation without the “transitory“ prefix2, commodity price increases, and the effect of Russia’s current situation3 thereon I’d like to look at the possibility of deflation45 — something I’ve avoided really thinking too much about myself given the plentiful online attention that this idea has been getting for some time already, but that I now think is a fine thing to look at given that MSM attention is looking in the exact opposite direction.

I’m going to look at this not the from the POV of “Bond markets are or aren’t buying it“ or “Is QE / bank reserves really ‘money printing‘?“ arguments — that I’m not going to be smart enough to really confirm or reject here anyway — but from the POV of Fat Tony’s “betting against fragility in the longrun”:

So the antifragile can lose for a long time with impunity, so long as he happens to be right once; for the fragile, a single loss can be terminal. Accordingly if you were betting on the downfall of, say, a portfolio of financial institutions because of their fragilities, it would have cost you pennies over the years preceding their eventual demise in 2008, as Nero and Tony did. (Note again that taking the other side of fragility makes you antifragile.) You were wrong for years, right for a moment, losing small, winning big, so vastly more successful than the other way (actually the other way would be bust) —- Nassim Taleb6 “Antifragile“

Cash as an allocation

First, an aside: I’d like to review the case for cash as a portfolio allocation in general — if only for my own edification and conviction-building for holding such an unexciting asset while every finance YouTube video being recommended to me is talking about the massive gains to be had in real estate, dividends, Bitcoin, $BABA, and VIX futures.

Cash = a low-duration, high liquidity USG bond ==> a non-zero Cash allocation should be part of any diversified portfolio

“Duration”, in the context of bonds, basically7 means that if interest rates on similar bonds rise/fall by X pps, then the price of your bonds needs to fall/rise by Y pps (to be a competitive price and yield vs the value of the cash flows of the new, higher/lower yielding bonds). Duration also changes with interest rates depending on the “convexity”8 — so if Duration is the derivative of bond price, Convexity is the second derivative.

So, if you own 10yr USTs with a present 1% yield to maturity (YTM) and a “duration” of 8yrs, and then new 10yr USTs started getting printed with a 4% YTM, then the price of your USTs would need to fall by…

8yrs * (4-1)%/yr = 24%

…to compete with the value of the cash flows of the new similar USTs. You would have had to have been holding those 10yr USTs for 24yrs just to break even in such a scenario.

Note, the IEF ETF (which invests in a basket of 7-10yr USTs) has an effective duration of 8.10yrs and an SEC yield of 1.30% — note that pre-2008 the yield on the 10yr was closer to 4-6%910. (BTW, the implied equity duration of the S&P 500 in 2010 was ~20yrs11. Given the increased growth/tech weighting it has now, I doubt that number has gone lower since then).

Here are some of my old notes on the duration risk downsides for various maturity bond funds — the calculation are from a while ago, but the numbers today should not be too much different:

IEF (7-10yr, avg=8yrs): Modified duration = 7.97 ==> price decline of about roughly 23.91-39.85% for a rate increase from 1.35% (current YTM) to 4-6%

TLT (20yr+): Modified duration = 18.59 ==> price decline of about roughly 37.18-74.36% for a rate increase from 2.27% (current YTM) to 4-6%

SHV (0-1yr): Modified duration = 0.37 ==> price decline of about roughly 1.48-2.22% for a rate increase from 0.04% (current YTM) to 4-6% (similarly for GBIL ETF)

JPST (0-1yr corporate debt and ABS): Modified duration = 0.71 ==> price decline of about roughly 2.47-3.90% for a rate increase from 0.52% (current YTM) to 4-6%

We can think of Cash as a bond as well — one with a virtually zero duration risk. Eg. Charles Schwab pays you 0.01% APY on cash in your brokerage account and we can do a lot better if we move just a bit further out on the yield curve12 — note that for my own purposes, I consider anything with a maturity less than 1yr to be “mostly good enough as“ Cash13:

In addition, Cash is has nominally14 no price volatility.

Well…at least your decline in Cash value was smooth and gradual, rather then volatile (I’ll go into why Cash still makes sense to hold on to at some size despite this debasement in a bit).

BTW, Cash is also the most liquid form of US debt. Liquidity being something in increasingly short supply in the markets at the moment, see “Benefiting from indexation, liquidity deficits, and vol“ in my recent post on market makers:

Indexation ==> shortage of “supply” / biodiversity of differing investment opinions (or at least their expressions in the market)

==> shortage of liquidity (b/c everyone in the market is expressing the same opinion (everyone is in the indexes and they all buy and sell the same things at same time))

I recently saw this article “Companies Are Flush With Cash—and Ready to Pad Shareholder Pockets: U.S. companies have authorized a record amount of share buybacks this year, a bullish sign for markets amid volatility.” Question: Why are they not reinvesting in the business? What kind of economic outlook would you have to be seeing to horde cash / pay yourself excess distributions, rather then reinvest in your business? I don’t think the answer is ‘a growing economy’.

Given these points, I do think that the amount of a portfolio that should remain allocated to cash at present is certainly not zero.

Zero rates = fragility, “High“ rates = global stability

“Americans will always do the right thing, only after they have tried everything else“, Winston Churchill

“[T]o avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely (ie without limit), to solvent firms, against good collateral, and at ‘high rates’”, Walter Bagehot

OK so, what is the possibly fragile thing to bet against here? Low interest rates.

Here we have the US Fed fund rates since 1970 — notice how crazy low our most recent decade of interest rates has been:

Now let’s zoom in on the trend in the FFR that started in 2016 — which was only smothered back down to zero in response to the COVID19 lock-downs and subsequent economic crash:

Why are low interest rates fragile? There are many that have cited why they will go up (and an equal amount making the case for the Fed being trapped into keeping inflation running hot), but here’s one that you may not have seen talked about much:

Low rates = supply chain breakdown = anarchy ==> Congress MUST raise rates (eventually)

Here’s a brief explanation of what I think this neocon blog post is saying:

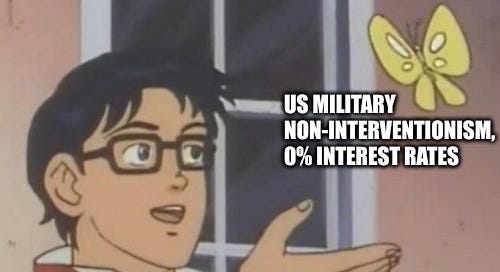

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Global supply chains require a carrot and stick to operate Carrot = high interest rates (> 2%, < 10%) Stick = US/NATO military interventionist supply chain security enforcement Low rates == USD yields nothing ==> nobody wants to work for USD (which at this point is zero-yielding monopoly money) == nobody wants to supply US with good and services in exchange for USD ==> people just work to maintain themselves and family w/out selling any excess output (consider the rising popularity of China's Lie Flat movement and Reddit's r\antiwork subreddit or the rising popularity of homesteading and "van life") ==> supply chains break down US military non-interventionism ==> Harder for people to supply + no foreign elite (puppet leaders or otherwise) to force people to output in excess ==> Supply chains break down ==> Congress needs to have the Fed raise rates back to pre-2008 levels + Fed selling its UST (to remove USD from circulation and make USD scarcer) + US/NATO military must re-engage in global interventionism and securing supply chains ==> Those who have saved Cash will be able to live comfortably on a nice big coupon yield (and not have had their 60/40 stock/bond portfolio annihilated on the duration risk leading to those rates). * Also, inflation ==> low supply of stuff low interest rates ==> lower output/hr ==> low supply of stuff ==> inflation ~ low interest rates ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Simply: Interest rates are the price of money. Raise the price of money, then solvent businesses will want to invest in production to sell stuff to collect more money and — more importantly — lenders will be more inclined to seek those opportunities to lend their money.

Think of it this way: You grow X apples and sell it to the US and get more 1s and 0s in your USD bank account worth X apples. You can spend those 1s and 0s on something else that is worth X apples or you can save those 1s and 0s and get a return of basically 0% — really the return is some negative number since the total supply of USD has been increasing15 against this 0% return. So the question is: What’s the point of producing excess apples beyond what you yourself need in exchange for USD? You’re selling your product/capital/labor for — at this point — literal Monopoly money; you’re basically just holding USD for the fungibility to exchange for something of lesser or equal value as there’s certainly no point in saving/lending your capital/labor for a near 0% future return at best on your risk/effort.

Notice that low interest rates can encourage consumption, but are actually discouraging production — again I point to China’s Lay Flat movement and Reddit’s growing r\antiwork.

There’s a Marxist theory that the time for Communism is when interest rates go to zero, because a 0% interest rate is a sign that the capitalists no longer have any idea what to do with their money — there are no good investments left and that’s why rates are zero. Therefore, all you can do at that point is redistribute the capital. —- Peter Thiel16

On top of that maybe you don’t even like living under the USD system (as I’m sure Russia, China, et al are thinking right now). At a certain limit — and maybe not even at an economically logical one (people are people after all) — it’s preferable to just barter with your nearer neighbors or simply not produce any unnecessary excess output beyond your own sustenance, rather than work to supply excess goods for these worthless assets they call USDs that aren’t really yielding any greater return than just bartering anyway (a simple example can be found here). In the end, there is less stuff produced to go around and thus the price of things goes up. Below is the BigMac Index — vs CPI — measured around 20 years before and after the start of QE in 2008:

As a corollary, we will — if this theory holds true — see entitlements being cut (when total supply chain disaster is visibly imminent to politicians (and by virtue, the Median Voter)). This partially addresses some of Murray Stahl’s argument in Horizon Kinetics’ 2Q2021 commentary on why the Fed “is trapped“ into hot-running inflation on the debt/GDP issue17.

(BTW, you can currently see some US action on the military side of things as of recently18 — and will certainly see more of it in the future19 as a reaction the disruptions caused by the Russia-Ukraine situation).

Final Thoughts

“This is one of the most important things I learned from him: the optionality of cash. He thinks of cash as a call option with no expiration date, an option on every asset class, with no strike price.” — Alice Schroeder on Warren Buffett

IMO, it’s not a matter of if, but when, rates are going to get raised. I don’t think this is a hugely controversial statement given that nominal rates are already crawling along the x-axis (it literally has nowhere to go but up), but I don’t really think investors are generally holding enough cash — I current have ~25% of my portfolio in cash (mostly from lack of finding anything super interesting to invest in) — relative to the kind of volatility of duration risk-off that would come from any serious hiking cycles if the Fed decides to get really serious about bringing down inflation (which I think is a very important tail risk for anyone betting on the inflation camp).

Murray Stahl of Horizon Kinetics and FRMO Corp had this to say about FRMO’s large cash position in 2014:

Cash and Equivalents. This segment comprises roughly 24.6%20 of total corporate assets. .

[…] It should also be obvious that our cash balances vastly exceed our normal operating requirements. We are therefore in a position to invest a substantial amount of capital should the opportunity arise.

[…] [C]ash is a quasi dormant asset that can be mobilized to increase return on equity. It is only quasi dormant as it does serve a collateral purpose, in part.

There are perhaps ways to the real-option value of cash held in a portfolio (see here: https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/17/5/1649/1581144#123770797), but I’ve not gone through that paper well enough at the moment to be able to make an exact determination on that. The basic conclusions I take away here, though, are that (and I’m going to use a bit of my own shorthand here)…

The amount of investment cash flow (CF) (either from dividends, distributions, or DCA’ed into your investment account from outside) that should be retained is never going to be 100% — generally dependent on CF volatility, the availability of growth opportunities, and investment cost (for our purposes21, I read this latter part as “valuations”).

The less cash holdings you have the greater your CF retention percentage should be.

The incentives of people for — though not necessarily the value of — retaining CFs is generally stronger when CF volatility increases or investment costs are low.

The value of cash holdings decreases when volatility increases because it is actually more valuable to retain CFs when vol is low because that low-vol environment is more conducive to delaying and planning out investments, thus generating more value. What I take from this is that in times of high vol, cash should be deployed — and as I write this, I don’t think the vol is here yet, that it’s probably coming.

$1 is worth > $1 when that $ is being retained to invest in future growth opportunities. I mean, this just makes intuitive sense if you think of it from a DCF POV: If you’re planning to invest in growth opportunities in the future that you maybe don’t see being presented today, then the CFs of the DCF equation on that cash is just zeros for the first few period terms (for however long you’re going to hold it for) and then — something like — whatever sustainable FCFE yield or ROCE you plan/think you’re going to be investing it at when you actually do decide to deploy it (and the availability (or lack thereof) of those opportunities is rather dependent in market vol and valuations).

So essentially…

Cash value ~ (1/Volatility) x (Investment cost) x (1/Growth opportunities)

...which could likely be simplified as...

Cash value ~ (1/Volatility) x (Investment cost)And IMO, vol is not currently where it could be heading as the Fed starts taking inflation seriously and — in terms of "investment costs" — I'll just leave this here:

So, right now, I think cash is looking pretty valuable.

Until and after this Fed rate hike series — IMO, possibly not too unreasonably far in the future — happens: You were wrong for years, right for a moment, losing small, winning big, so vastly more successful than the other way (actually the other way would be bust).

See

https://www.gmo.com/americas/research-library/let-the-wild-rumpus-begin/

Though, at a certain point, how long is it until you’re in a-broken-clock territory?

Though this is being discussed under the rather disingenuous cover of a “Putin price hike“ narrative, despite Brent and WTI crude oil prices breaching pre-pandemic levels about 1yr before Russia invaded Ukraine and sanctions being placed on Russia.

BTW, I would think that the recent sanction on Russian oil would actually be conducive for lower oil prices IRL (ie. beyond the financial market for commodity derivatives) given that big commodity traders (eg. Vitol, Cargill, Glencore, et al) can now buy that Russian Oil at a steep discounts on the black market before bringing it online to the market as Just Oil for a nice spread. I downloaded “The World For Sale“ on Audible last year and I suspect it is going to percolate into the mainstream zeitgeist to a greater extent in the coming months.

And I’ve been long energy inflation et al since 4Q2021 — tracking the bullish thesis for even longer then that.

Note that there is also an emerging risk of consumption tapering and subsequent demand destruction https://mishtalk.com/economics/real-wages-decline-12-times-in-the-last-14-months

TBH, I think Taleb clearly comes off as childishly-petty and egotistical in both his books and social media, and most of what he writes about already exists in various forms across writings on decision-making, investing, etc, but I think the the quote here is still a good one; This tweet is a good quick summation of how I perceive Taleb himself:

… But if people find what he writes about to resonate and be personally valuable to their lives, then, well, good for them.

https://home.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/interest-rates/TextView?type=daily_treasury_yield_curve&field_tdr_date_value_month=202203

The argument can also be made for a higher risk and reward way to hedge duration risk being investing in “value” vs growth stocks

“Low-Duration equities have relatively more of their value in near-term cash flows, and because a pandemic shutdown curtails near-term cash flows”, DECHOW, P.M., ERHARD, R.D., SLOAN, R.G. and SOLIMAN, A.M.T. (2021), Implied Equity Duration: A Measure of Pandemic Shutdown Risk. Journal of Accounting Research, 59: 243-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12348

BTW, this quartile of the market is relatively cheaper than it’s ever been:

Not accounting for the hidden cost of inflation

The avg growth rate in M2 money supply from Dec 2017 - Jan 2022 was 7.16%.See https://ycharts.com/indicators/us_m2_money_supply_yoy

My understanding is that in Marx’s time, he — and many others — believed that in their post Industrial Revolution world that civilization had effectively reached the “end of history” and so all that was left to do with capital was distribute it to build out a Marxist utopia.

Note, the last time I checked, FRMO’s balance sheet also held a significant amount of cash. Great minds think alike I suppose ; )

I didn’t read this before deciding my own similar portfolio’s cash position, I promise.

Note that this paper was written with fully-equity-backed businesses in mind, so I am making some analogous leaps here, but I don’t think I’m departing too much from the ideas of the paper itself.