Like Weeds In A Garden: The Zen Of Managing A Portfolio Without Managing A Portfolio

An emergent "strategy" of doing nothing --and why buybacks are not equivalent to dividends

For several years I lived on a steep hillside in a decrepit summer cottage that had what a real estate agent called “charm.” Which meant it was a shack with a view. In keeping with the spirit of the house, I let the yard go “natural,” letting what wanted to be there be there and take care of itself without any help from me. I remember announcing from the front porch to all living things in the yard: “You're all on your own. Good luck.” —- Robert Fulghum, “All I really need to know I learned in kindergarten” 1986

“When you realize nothing is lacking, the whole world belongs to you”

“Shake It Off”, Pareto style —and by “it” I mean the other middling 80% of a portfolio

In defense of degeneracy, junk food, and strategic drift… (or simulated annealing, as I call it)

*For the purposes of certain references I might make to “FCF”, note that I usually mean cashflows from operation (CFFO) less maintenance capex (as opposed to lumping all capex together regardless of whether it is used for growth or for maintaining the existing business); maybe call is DFCF for “discretionary FCF”. I’ll admit it’s not always obvious when looking at an annual report or a screen of compiled financial data whether a certain amount of spending that is lumped into capex line items is mCapex vs gCapex, but sometimes it is and sometimes it can be reasonably determined by reading a bit more about the business + looking at the footnotes. This related article from the great compiler Michael Mauboussin is interesting: https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_underestimatingtheredqueen.pdf.

Intro

Warren Buffett wrote something interesting in Berkshire’s 2022 annual letter to investors; it included a section called “The Secret Sauce”. In this short section, Buffett reflects on the long-term success of Berkshire Hathaway's investments in Coca-Cola and American Express. Over the years, the cash dividends received from these holdings have shown consistent growth, from $75MM in 1994 to a 10x of $704MM in 2022 for Coca-Cola, and from $41MM to a 7x of $302MM for Amex. While these dividend gains alone may not be remarkable, their impact on the stock prices of the respective companies has been substantial1. BRK’s investments in Coca-Cola and Amex have grown to a value of $25bn and $22bn, respectively, accounting for approximately 5% of the company's net worth.

Buffett contrasts this with a hypothetical scenario of an investment with a cost basis allocation similar to that of his Amex bet that —unlike Amex— had remained stagnant and highlights how this underperforming investment as a portion of BRK’s portfolio would now be de minimis and contribute minimally to BRK’s overall income. “The lesson for investors: The weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom. Over time, it takes just a few winners to work wonders. And, yes, it helps to start early and live into your 90s as well.”

This got me thinking again about the “coffee can” portfolio strategy —or the Kahnweiler method, as Murray Stahl might call it— which involves buying and holding a portfolio of high-quality stocks for the long-term, usually five years or more, and typically consists of 10-20 stocks from different sectors and industries that are high-quality companies with a an ability to generate consistent growth and profitability2 —so there’s technically no moon-shoots, net-nets, or last-puff-of-the-cigar, stock flipping allowed with this.

I’ve written a bit about this idea in the context of Horizon Kinetics founder Murray Stahl and my various observations about his investment style here. With this strategy (and his interesting way of thinking through investments), Stahl’s Paradigm Fund has outperformed the market over the past 10 years —largely due to a concentrated position in Texas Pacific Land Corporation (TPL), which was initially bought for their dividends, share buybacks, and land value optionality and has now been accumulated over nearly 20 years to become an outsized concentration for the fund as the discovery of shale oil and fracking have rocketed the stock well past 100-bagger status. (There’s currently a lot that could be said about TPL as I write this, but that is not the focus on this post).

… Meanwhile, making this track record even more impressive —aside from the fact that the Paradigm Fund does not include any of the FAANG or Tesla stocks that have been pulling a lot of heavy duty for the S&P 500— over the past 15yrs, active management as a class has underperformed passive investing around 90% of the time; S&P Global tracks this kind of thing via the S&P Indices versus Active (SPIVA) scorecard —it’s an interesting table to scroll through:

In any case, this post is not about Stahl in particular —though I will reference him again later— but rather some general thoughts and connections on this style of emergent portfolio concentration. I ultimately plan on constructing an experimental portfolio based on this overarching idea and am mostly using this post as a way to log some of my initial thoughts on the topic.

“When you realize nothing is lacking, the whole world belongs to you”

One of the central ideas in Zen Buddhism is the concept of “non-doing” or “doing without doing.” This idea suggests that by letting go of our preconceptions and specific desires, we can attain a state of effortless action that arises naturally from our present-moment awareness. The themes of non-doing and letting go of our desire to control events can be applied beyond the realm of spiritual practice and into areas such as economic forecasting. Zen teaches us that trying to predict the future or control macroeconomic events is a futile effort; from Seth Klarman’s “Margin of Safety”…

“By way of example, a top-down investor must be correct on the big picture (e.g., are we entering an unprecedented era of world peace and stability?), correct in drawing conclusions from that (e.g., is German reunification bullish or bearish for German interest rates and the value of the deutsche mark), correct in applying those conclusions to attractive areas of investment (e.g., buy German bonds, buy the stocks of U.S. companies with multinational presence), correct in the specific securities purchased (e.g., buy the ten-year German government bond, buy Coca-Cola), and, finally, be early in buying these securities. The top-down investor thus faces the daunting task of predicting the unpredictable more accurately and faster than thousands of other bright people, all of them trying to do the same thing.”

…Instead, we should strive to allow events to unfold naturally without resistance or fear, embracing uncertainty and volatility as a necessary part of life and as an essential aspect of investing (which, in the absence of aggregate uncertainty, would have no upside to capture).

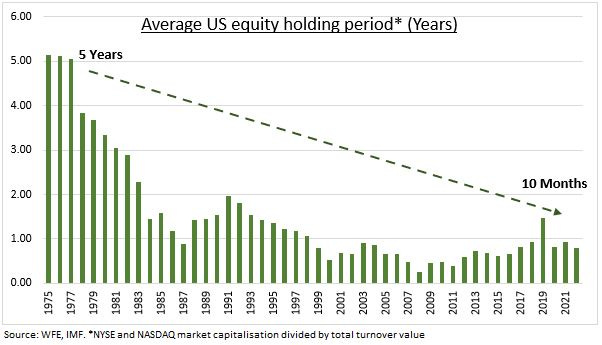

Sometimes, the best way to achieve a goal is by not trying to control or manipulate events, but by allowing things to happen naturally, without resistance. This is a view that is evidently challenging for people —myself included— to actually put into practice in a world that values control and predictability, with the average portfolio turnover of actively managed US funds sitting at 63% in 20193 (i.e. by the end of the year, a typical fund would have replaced more than half of the businesses it started the year with). The average equity holding period for an individual stock in the U.S. is now just 10 months, down from 5 years back in the 1970s.4

I find this story from Morgan Housel interesting… (https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2013/07/22/keep-investing-as-simple-as-possible.aspx):

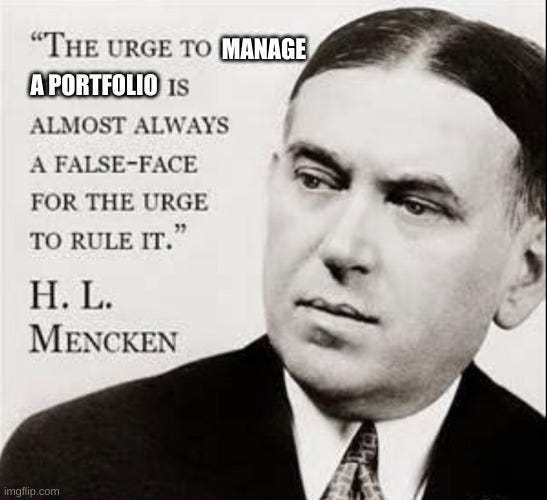

There are no points awarded for difficulty in investing. The investor with the most complicated model or the most elaborate theory doesn't always win. Indeed, elaborate theories can often be the fastest route to self-delusion. The Motley Fool's Seth Jayson put it nicely: "It begins to sound fatalistic, but I have come full circle on this to the idea that simple rules work far better than deeper thinking, because most of that deeper thinking is just an exercise in bias confirmation."

In 1981, Pensions & Investment Age magazine published a list of money managers with the best track records over the previous decade. One year, a fellow named Edgerton Welch of Citizens Bank and Trust Company topped the list. Few had ever heard of Welch. So Forbes paid him a visit and asked him his secret. Welch pulled out a copy of a Value Line newsletter and told the reporter he bought all the stocks ranked "1" (the cheapest) that Merrill Lynch or E.F. Hutton also recommended.

… and it reminds me of a commentary by Horizon Kinetics’ Murray Stahl titled “Can a Bad Portfolio Manager beat the S&P 500?”. His conclusion is that “[t]he answer to this question is decidedly affirmative.” The reason is essentially that, while the hypothetical “bad PM” in the story simply gives up on trading from the outset and does nothing each year beyond continuing to make buy decisions, over time, the small number of winning stocks in an initially diversified portfolio (assuming an initial construction with a normalized distribution of losers, so-so’ers, and outperformer stocks) will come to dominate the percentage of the total holdings, while the worst that the middling or losing stocks can do is die and go to zero, never to drag on performance again.

With such a view of an investment portfolio, the question then is not about trading, doubling down, or trimming positions, but narrowed to the more essential questions of how to pick more winners and less losers (emphasis on the latter) and where questions of diversification might only come into play when considering the economics of a prospective new position (vs ‘has this position succeeded too much and gotten too big?’). At the very least, you end up with a organically de-worsified portfolio over time.

All of the rules that he laid out, he broke all the rules, and he owes all of his success to one investment. And if you remove this one investment from that investor’s career performance, if you just take this one stock out, the career performance drops to average. The one stock that he’s talking about is GEICO and the investor is himself, Ben Graham. If you look at Ben Graham’s lifetime performance, if you remove one investment that he made in GEICO, his performance is average. And by the way, buying GEICO broke every single rule that Ben Graham put in his own book. —- Morgan Housel5

I also add to this the process of continually re-evaluating if the business model and business/regulatory environment that made your winner winners still holds and subsequently having the courage to sell when a thesis is broken and no newer one can be determined or simply becomes irrelevant —and the same for determining of existing losers are losers because your original thesis was wrong or is simply not relevant. In both cases, I like to think of it as the humility and courage to (rationally) chicken out6. Mentally giving yourself this leeway also can help reduce the underconfidence risk of analysis paralysis (on buying decisions) and reduce the overconfidence risk of holding/riding falling knives (re. sell decisions); you don’t have to make it back the way you lost it.

Sometimes I’ll even just bail on a new position on the not-directly-economic basis of if it crossing below, say, 2x multiple of the 20-50 day average true range (ATR) value (see Richard Denis and Turtle Traders or Soros on Karl Popper and uncertainty/fallibility) —even smaller multiples for larger starting position sizes— if I’m not too confident in a position (often) where the market may be seeing/pricing something I’m not understanding or if the position just does not have a concrete time or event catalyst (eg. generally cheap stocks or those that I think will benefit from some larger trends I think will play out over time eventually at some undetermined point, just maybe not this month).

I think of this lens a bit like surfing: You can do all the research in the world to choose the beach (sector/theme/etc) and you can paddle out and choose your perfect spot or break at that beach (individual stocks or baskets of stocks), but when it comes to actually catching a big wave you kinda just have to sit there a wait for one to form; they don’t show up just because you started paddling, no matter how hard (or how much of your portfolio you invested) —but there will be signs.

Of course, even this analogy can be taken too far and I understand how a lot of technical analysis and charting is seen as “astrology for men”, but I think there is merit to the basic ideas of not totally disregarding trend signals. (Personally, based on the ideas of Druckenmiller on liquidity and Ted Warren’s “How to Make the Stock Market Make Money for You”, I tend to like to look at certain liquidity measures and a few basic trend signals.)

Pictured above: Market open after Bitcoin just crossed it’s 50 day moving average for no discernible reason; I of course am patiently waiting for the 55 day cross. (This is joke, do not do this).

(This oft-used strategy of “start small, then wait and see with a diminishing or widening stop-loss as we average up” makes it hard for me to write about individual stocks or ideas as I might spend time writing about something, yet the amount of words should not be construed as being too largely correlated with the level of current conviction or position sizing (which I think is often implicitly assumed) as I might have a 2%-5% position one day, then totally sell out the next, all the while my overall interest in the company, business model, or setup in the long-run still being very high —it just might not have been the time to hold on the the ride, either based on market signals I’ve systematically agreed to adhere to (despite what I might feel about the situation) or my interpretation of some piece of fundamentals data or management comments.)

Meanwhile, for reasons I’ll come back to later, I do tend to pay attention much less and let existing winners run after I’ve been able to realize near 100% payback on my cost basis for a position and the bar for bailing those positions tends to be a lot higher after that, so long as the basic business model holds or the moats remain strong or growing. They say bad traders turn bad trades into long-term investments; I often look at all new positions through the lens of a “trade” and try to keep losses from bad ones de minimis and allow good ones to grow into long-term investments (with increasingly lenient trailing stop loss thresholds and increasing focus on fundamentals and moats).

Any way the wind blows, doesn’t really matter to me

“If you try to represent the stock/bond relationship with one correlation statistic, it denies the causality of the correlation. Correlation is just the word people use to take an average of how two prices have behaved together. When I am setting up my trading bets, I am not looking at correlation; I am looking at whether the drivers are different. I am choosing 15 or more assets that behave differently for logical reasons. I may talk about the return streams in the portfolio being uncorrelated, but be aware that I’m not using the term correlation the way most people do. I am talking about the causation, not the measure.” […] Drivers are the cause; correlations are the consequence. In order to ensure a diversified portfolio, it is necessary to select assets that have [or will have in the future] different drivers. ~~~ Ray Dalio in Jack Schwager’s “Hedge Fund Market Wizards”

In sailing, there is a concept of “points of sail” which refers to the different angles at which a sailboat can travel relative to the direction of the wind. A boat’s position and trim (orientation) of the sails relative to the direction of the wind can significantly influence the speed and efficiency at which a sailboat can travel in any direction.

In an analogous manner, depending on the direction and strength of the macroeconomic winds, different types of investments can grow faster or slower. One manner in which I like to diversify my portfolio is by attempting to position various ‘ships’ / categories of baskets of positions simultaneously across all “points of sail” such that the total portfolio can benefit in some material way regardless of particular direction the ‘winds’ are blowing. If we imagine this circle of ships as investment positions and the total return of those positions as represented by the distance from the center of the intersection of the various points-of-sail anlges, our goal then is to opportunistically add, maintain, or retire “ships” that, as the winds blow over time, will ultimately encompass the greatest possible area without ever “backtracking”. The goal is to have positions that can produce great amounts of cashflows when the winds are in their favor, while also being able to make a decent return when they are not (or at the very least, not lose ground/money in these unfavorable times).

If I can find a company that is currently in the prevailing Close Reach or No Go positions (and it’s growth expectations indicate as such), but is still able to tread water for the foreseeable future and can take off by orders of magnitude if the winds ever change in their favor such that their current “position”/fundamentals become Run angles, then I will still be very interested in buying if that perpetual call option seems cheap. Two steps backwards in the unfavorable times is acceptable if they’re taking five steps forward in the favorable times —generally sized according to both the likelihood of their fundamentals holding up until such a time and the probability of that time coming sooner rather than later, of course.

Mintzberg and emergent strategy

Circling back to Buffett’s earlier comment on flowers, weeds, winners, and withering, Henry Mintzberg is a highly recognized management expert and wrote an article in the Harvard Business Review around 2016 (which I can no longer find to link to) suggesting that strategies do not always need to be carefully planned and cultivated “like tomatoes in a hothouse.” Instead, strategies can emerge organically like weeds in a garden, where they take root in all kinds of strange places and eventually become valued patterns in an organization's activities.

These emergent strategies may displace existing deliberate ones, and once recognized as valuable, can be selectively propagated. He argues that managers should simply recognize and intervene when appropriate in this emergent process rather than preconceiving strategies in a top-down fashion. Therefore, from an executive management perspective, it is important to establish a flexible structure that encourages the generation of a wide variety of ideas and allows for the organic emergence of the best strategies.

Mintzberg’s ideas (https://mintzberg.org/blog/growing-strategies) around “grassroots strategy formation” for executive decision-making are what most crystallized these concepts of coffee can investing for me over time as I think they are easily massaged into this organic, free-range investing perspective. He notes that…

Ideas become strategies when they pervade the organization. Other engineers see what she has done and follow suit. Then the salespeople get the idea. Next thing you know, the organization has a new strategy—a new pattern in its activities—which might even come as a surprise to the central management. After all, weeds can proliferate and encompass a whole garden; then the conventional plants look out of place. Likewise, newly emerging strategies can sometimes displace existing deliberate ones.

… Replace “ideas” with “investments”, think of “strategies” as “favored business models or investment ideas”, and think of “the organization” as your portfolio. I am reminded of the “scaled economics, shared” business model, so favored by Nick Sleep that Amazon.com was allowed to become over 50% of his entire portfolio and Costco Wholesale around 25%. In 20097, Sleep had this to say to investors…

Zak and I think of the Partnership in terms of business models deployed by our investee firms. The names we use to describe these models are not that catchy but please bear with us. The largest group making up over half the Partnership are, no drum roll required, scale-economics-shared; next comes discounts-to-replacement- cost-with-pricing-power (I warned you) at around fifteen percent; hated-agencies fifteen percent; super-high-quality-thinkers just under ten percent. The Partnership has twenty investments but a noticeable concentration in ten, which make up around eighty percent of the portfolio, and for those with sharp eyes around thirty percent of the Partnership in one investment.

Mintzberg notes that the processes of proliferation of strategies may or may not be consciously managed. They may be allowed to simply spread by “collective action, much as plants proliferate themselves”; in this same way, any particular position might proliferate itself through the basis points of your portfolio. Though, he also allows for the commandeering of an emergent strategy in an organization once it’s reached a certain critical mass to insert executive action into a strategy going forward and I’m not totally convinced that this is something that equally applies to portfolio management; why mess with a process that was doing well without you?

[Friedrich Nietzsche believed that] The aspect of the whole is much more like that of a huge experimental work-shop where some things in every age succeed, while most things fail; and the aim of all the experiments is not the happiness of the mass but the improvement of the type. Better that societies should come to an end than that no higher type should appear. —- Will Durant, “The Story of Philosophy”

This idea can also be seen in a discussion “On Concentrated Positions, ‘Locking in Profits’ and ‘Trimming’” in the Horizon Kinetics commentary here8 which talks about simply buying a basket of select stocks and simply letting the losers lose and winners run to dominate the weightings of the portfolio over time into large concentrations of a few winners (as well touching on why this is structurally difficult for institutional investors and psychologically difficult for humans in general).

HK co-founder Steve Bregman describes this concept as ‘the secret formula for investing success’ that anyone can do, but that he's confident few will earnestly implement —when I think about the concept of investing ideas that are made un-investable due simply to institutional imperatives and human biases, sitting and doing nothing while letting positions run concentrated certainly seems to qualify:

“First, you have to choose a large enough number of equally-weighted stocks so that they encompass a normal distribution of possible outcomes – the good, the bad and the middling. Financial statisticians might agree that 35 or so names are sufficient9. Second, don't trade it. You can make no changes, you can’t harvest your winners and double up on your losers, etc. [...] Each year, the negative outliers become smaller weights, and even though they’re doing horribly, they matter less and less. Eventually, they’ll be a rounding error. If the two 'smart penny' stocks keep outperforming, they will eventually come to dominate the portfolio. They’ll expand fro equal 3% positions to 5% positions in a few years, which doesn’t seem like a lot. But in year 10, if all the other stocks in the portfolio appreciate their 6% per year, these two stocks will be 22% of the portfolio, and the annualized portfolio return will be 7.4% instead of 6%. The portfolio will be worth 13% more than the indexed portfolio.”

I would, however, ride along with the idea that, at a certain critical mass, your certainly not going to be able to treat all of your portfolio positions the same in terms of the amount of time spent on maintenance/monitoring diligence —I don’t think, honestly, that you could then fault anyone for shying from this strategy if it were to result in concentrations in businesses whose business models, economics, and 2nd derivative KPI drivers were found to be very opaque and hard to follow; perhaps best to simply avoid those in the first place, regardless of position size. Again, pairing this portfolio Darwinism with a sound initial selection strategy and process would be useful here, rather than simply setup a snapshot of an equal-weighted market index.

At first Nietzsche spoke as if his hope were for the production of a new species; later he came to think of his superman as the superior individual rising precariously out of the mire of mass mediocrity, and owing his existence more to deliberate breeding and careful nurture than to the hazards of natural selection. […] “Woe to the thinker who is not the gardener but the soil of his plants!” Who is it that follows his impulses? The weakling: he lacks the power to inhibit; he is not strong enough to say No; he is a discord, a decadent. —- Will Durant, “The Story of Philosophy”

Self-organizing criticality

Murray Stahl acknowledges this emergent strategy as part of his own investing philosophy in a 2008 HK commentary Q&A where Stahl says…

At inception, standard position size for me is usually 2%. I don’t change it radically over time, because I’m a big believer in the mathematics of what’s called self-ordered criticality. Ultimately, if you leave the portfolio alone long enough, whatever your best position is will eventually become your largest position. In other words, let the portfolio do the work. […] Given your view of the enterprise, if you thought it reasonable to establish a 2% position, and the company lost half its value, and all else remained constant, if you altered the position to make it a 2% position again then you’re effectively making it a 3% position. That should be done if it is concluded that the risk/reward at the lower level is far superior to all the other companies that are in the portfolio.

As an example, I’ve set up an equally-weighted hypothetical portfolio of (what are, today) generally well run businesses, so there is a bit of deck stacking here, but I think the point remains valid as an analogy for selecting good businesses to begin with (as we already know what’s going to happen with the worse or now-bankrupt businesses). I then allowed the backtest to run for 10 years from 2012 (simply the earliest available starting date of the youngest component of the portfolio) to the beginning of 2022 with all dividends reinvested and no re-balancing of the portfolio.

We can see that by simply standing aside and letting the portfolio run unattended 1) the portfolio handily beats the market index and 2) in the course of this, a few outstanding businesses drive the outperformance and come to dominate a larger portion of the portfolio (in this case: Constellation Software, Facebook (now Meta), Take Two Interactive, and Texas Pacific Land Trust); continually re-balancing positions would have been counterproductive to this process.

One thing I thought was interesting was that I had initially felt like I might have been stacking the deck a bit much by including FNV, ROP, and WINA —who, with hindsight bias, I was of the opinion would be major winners— but those positions actually shrunk over time on a relative basis, while I did not expect TTWO to end up as such a significant holding in time; the self-ordering portfolio allows that room for humility in your investment process.

“Truth, like gold, is to be obtained not by its growth, but by washing away from it all that is not gold.” —- Leo Tolstoy

Further reading on this concept of “self-ordered criticality” can be found here.

An aside on portfolio stock count and “diversification”

Indeed, a patient and level-headed monkey, who constructs a portfolio by throwing 50 darts at a board listing all of the S&P 500, will – over time – enjoy dividends and capital gains, just as long as it never gets tempted to make changes in its original “selections.” —- Berkshire Hathaway Annual letter, Warren Buffett, 2020

At 2pps per position, that would leave a portfolio with 50 different stocks. This is well above the 20-stock limit of effective diversification as popularly cited from Burton Malkiel’s 1973 “A Random Walk Down Wall Street”:

However, this diversification lower limit is challenged by modern portfolio theorist William Bernstein10 in a fall of 2000 blog post, some 30 years after the publication of Malkiel’s book. The argument is based on the high variance of the terminal wealth dispersion (TWD) of possible 15-stock portfolios; the final 10yr annualized returns on 98 (initially) equally weighted, randomly selected, 15-stock portfolios11 found that 75% of them failed to beat the S&P 500 during that back-testing time period of 1989 to 199912.

Bernstein also points out that this does not even consider the survivorship bias of the stocks involved in constructing these portfolios; i.e. his backtest necessarily precluded the possibility for selected stocks to have gone bankrupt and completely disappeared by the end date of the backtest since those were not available to select as starting positions from the dataset he had to work with, which is not a situation that applies to actual investments being made in real time. The reason for this under-performance by the majority of backtested portfolios?

“The reason is simple: a grossly disproportionate fraction of the total return came from a very few "superstocks" like Dell Computer, which increased in value over 550 times. If you didn’t have one of the half-dozen or so of these in your portfolio, then you badly lagged the market. (The odds of owing one of the 10 superstocks are approximately one in six.) Of course, by owning only 15 stocks you also increase your chances of becoming fabulously rich. But unfortunately, in investing, it is all too often true that the same things that maximize your chances of getting rich also maximize your chances of getting poor.”

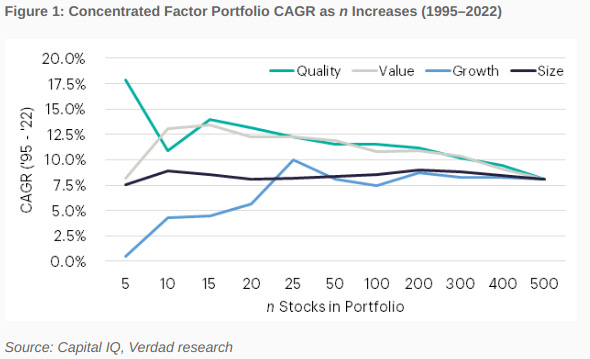

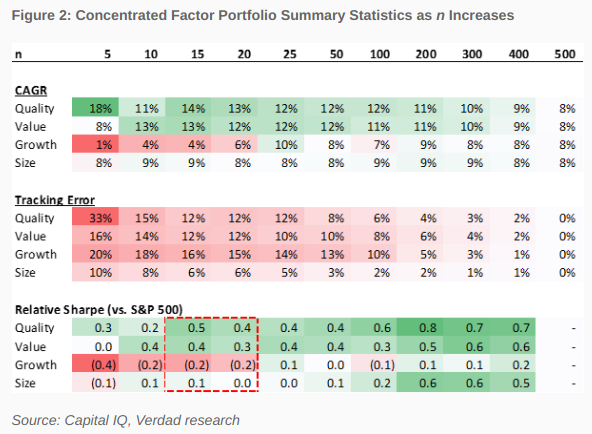

Somewhat addressing this TWD issue, we can look to a more recent short article from Verdad Advisers, LP, that I recently saw tweeted out by “100-Baggers” author Chris Mayer13. Unlike the randomized construction of the Bernstein backtest, the backtest here uses factor analysis to rank stocks for each year from 1995 to 2022 and construct and annually rebalance portfolios of 5 to 500 stocks, from the 500 largest US companies, themed on factors of value, growth, quality, and size; the results here generally agree with the 15-to-20-stock observation (not in terms of diversification, but of maximizing CAGR among the constructed portfolios).

However, it’s not specified if the portfolios where constructed with equally-weighted stock allocations or what. It should also be noted that this backtest involved annual rebalancing, which the Bernstein backtest did not do —aside from the particular, annually equal-weighted, “market portfolio” he mentions in his post.

At 50 stocks for a portfolio, it’s arguable that investing in an ETF would be an easier solution. The main issue I see is that a mutual fund or ETF is not a permanent capital vehicle and so can never offer opportunities to take advantage of market pessimism at the fund level (and if you have a manager you like, that’s the exact kind of situation in which you would most want to be buying); I write a bit more on this idea in the post here.

Furthermore, most indexes are based on rules that implicitly prevent concentration of investments, yet this is exactly what we are looking for when attempting to coffee-can a portfolio and let Pareto distributions aggregate percentage points around the winning stocks. For example, the CRSP US Small Cap Index —which is the benchmark index used by the Vanguard Small-Cap ETF— is rebalanced quarterly based on a calculation of the composite companies’ relative market caps14 15.

I’m fine holding stocks in a bundle a bit larger than the 10-20 limit followed by the “100-Baggers” and punch-card philosophy followers; letting these holdings DRIP (or otherwise grow via reinvesting) their way to becoming a larger or smaller concentration of the portfolio over time. For example, Murray Stahl had this to say when I asked about the composition of FRMO’s various LP investments in the 2QFY2022 shareholder meeting:

Ultimately, even though it’s nowhere near the position size of TPL, the position became sufficiently large so that the dividend flow of Mesabi can pay for more Mesabi. That means it’s become a self-replicating position, growing organically. And that’s the goal, to find several positions like that. Ultimately, a position like Mesabi will continue to grow, compound, really, creating more and more dividend flow. Eventually it would become sufficiently large that the share purchase requirements from the dividend flow would exceed our ability to buy more shares, in which case we’ll find something else to buy. […] We stick a little money in there, we get a little dividend flow, the thing becomes self-replicating, and after a while, even without inflation, it becomes meaningful.

In any case, I tend to use a standard starting position size closer to 4-5pps per position —accumulated over some weeks to diversify across time— for my own purposes as there are often businesses that themselves function as diversified, non-rebalancing, actively managed ETFs or portfolios of sorts; a company like API Group Corp. could be thought of as a non-rebalancing portfolio of statutorily mandated fire/life safety inspection businesses, OTC Markets Group is a kind of beneficiary on the overall activity and health of the OTC markets outside of the larger subset of stocks that make up most indexes and thus most fund flows, there’s —my personal favorite— FRMO Corp. as the most responsibly-run, shareholder aligned, inflation-minded portfolio that includes an vertically integrated Bitcoin business, and more obviously Roper Technologies with their large portfolio of industrial software businesses comes to mind here.

You could also argue that there are indeed ways to reduce systemic risk in a portfolio with less individual positions —in exchange for, perhaps, more diversified unsystematic risks— by selecting stocks that are presently outside or ignored by the fund flows of the global passive/index investing complex, but that’s a different discussion.

Greater (meta) diversification can also be gained by equal-weighting a portfolio, not by diversifying percentage point across many different stocks, but across different possible economic environments. I like to use the diagram here as a helpful reference:

Basically, one could start with equally allocated percentage points of a portfolio to each zone of economic possibility —or weighted based on your confidence levels about which macro futures were most/least likely— and distribute those points across various stocks as they saw fit. For example, here’s how I think about the RENN Fund’s diversification (one of my larger holdings)16, with the business logo sizes here generally corresponding to the size of the position in the fund:

********** UPDATE 20230526: I recently saw a paper here (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3710251) that used a longer backtest period (30 years from January 1990 to December 2020) than these other observations, across a global portfolio of 64,000 global common stocks, which found that “stock market wealth creation is highly concentrated; just five firms (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Tencent) account for 10.3% of the $US 75.66 trillion in global public stock market net wealth creation in our sample. The best performing 0.25% of firms accounted for half of global net wealth creation and the best performing 2.39% of firms accounted for all net global wealth creation.” It should be noted that around 1/3rd of this sampling period (2009 - 2020) were during during a period where interest rates were the lowest in history —which we’ve presently reverted from, greatly, at the time of my writing this— which is something that should be kept in mind when looking at the ‘winners’ of this backwards-looking sample set.**********

********** UPDATE 20231224:

I recently saw this interesting video on the ecosystems of life within the sandstone pothole pools of the Moab desert and it reminded me of this economic-quadrant based meta-diversification idea.

These various plankton and shrimp that have not evolved much since the Mesozoic Era may live in tiny, singular, isolated pools carved into the sandstone geography of the Moab over millions of years. These ecosystems go through periodic dry seasons where these pools can dry up entirely and the animals that live in these pools have had to evolve a number if diverse ways to survive.

“The shrimp are aquatic, period. […] You know, we all say don't put all your eggs in one basket, but these shrimp, they're stuck in that one basket they watch that basket by producing eggs that hatch under different conditions; that even the same clutch will hatch under different conditions.”

(More on these ecosystems can be found in a short read here: https://geochange.er.usgs.gov/sw/impacts/biology/vernal/)

I always take it as a good sign when my investment strategy can be easily analogized to something that comports closely to natural processes or, vice versa, where one can easily see how certain natural process can be analogized to investment strategy or ideas. Barring evolutionary algorithms, nature is the most diverse, longest-running, and widest-scoped steel-manning process one could pull lessons from.

(Evolutionary algorithms are another interesting concept if you want to read more on them; such class of algo was used to produce the radio antenna shown below).

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolved_antenna; The 2006 NASA ST5 spacecraft antenna.)

**********

“Shake It Off”, Pareto style —and by “it” I mean the other middling 80% of the portfolio

The music industry is a business that is all about finding the next big thing. A few successful artists generate the majority of revenue for record labels, so it is important for labels to take calculated risks in signing and promoting unknown artists.

One example of this can be seen in the case of Taylor Swift who was signed to a small record label, Big Machine Records, when she was just a teenager. The label took a risk on her by investing in her development as an artist and promoting her music; Swift's early success was not a guarantee, but the label believed in her potential and invested in her regardless.

Of course, not every risk pays off. For every Taylor Swift, there are dozens of artists who sign with record labels and never achieve mainstream success. However, the potential rewards of finding the next big thing are so great that labels are willing to take these risks so long as these wins can cover the remaining losses. In the end, the music industry is a business of probabilities. The more risks a label takes, the more likely it is to find the next big thing. And when it does, the rewards can be enormous.

As Swift's career took off, she became one of the top-selling artists in the music industry and generated significant gains for Big Machine Records. (However, their relationship eventually soured, and Swift left the label for a new deal with Universal Music Group. This move was likely influenced by the fact that Swift had become so successful that she could negotiate for more favorable terms and retain more control over her music and brand.)17

Of course, to the benefit of investors in the stock market, unlike with Swift and the record label who invested in her, public companies don’t generally have control on who owns their stock18.

From the interesting Acquired podcast episode on Taylor Swift (https://www.acquired.fm/episodes/taylor-swift-acquireds-version), they have a discussion re. the value creation/capture of the music label business…

When you sign a distribution deal where a record label fronts you the money, you make the album, they then own the master, your royalty stream—again, independently negotiated—but you only end up with like 10%, 15%. Maybe if you're a really big artist you can get like 20%, 22%.

In passive investing we can kind of think of this as capital returns to shareholders relative to total operating cash flow per share (minus maintenance capex). The case of owner-operated OTCM is a good example of this —perhaps a lesson to stick with management with evidence of integrity and incentives that align as close as possible with the economics of outside shareholders.

… And of course it’s not always obvious that you’d want a big return of capital from an investment, anyways, vs retaining cash for reinvestment if the business has viable growth prospects and can earn a high incremental ROIC above WACC, CoE, or whatever your personal hurdle rate might be for the determined risk.

What really caught my ear in this podcast episode was the discussion on the power law dynamic (or Pareto distribution) that characterizes the music label industry:

The last one that I want to dive into a little bit here is that advances interestingly are a clear sign of a power law dynamic where you mentioned it's like book publishing, we talked about how it's like venture. It's the same thing in all these things—music, books, and startups—where having the big winners in your portfolio is really what matters.

At one point, I had a book agent tell me that America basically picks one book a year to all read together. It's the Michelle Obama book or it's whatever it's going to be. You don't know what that's going to be ahead of time. You don't really care that much about recouping your advances on the losers. All you care about is making it so that in your portfolio, you get the book that America reads every year.

It's just so similar to venture capital. The way that the payback works is so similar to where, okay, an advance and then you recoup against the royalties. What's preferred stock? The first X amount goes to the capital provider in exchange for the capital they've provided and then they participate with some split in whatever outcome is after that. I don't want to quite get into the nuances of participating preferred and how it's slightly different, but the fact of the matter is, these contracts that seem predatory, and I'm not going to argue yet that they're not predatory, but what they're doing is basically making sure that they cover their losses.

There's this interesting human nature thing where if you look around and you're the winner, and you realize you're the one subsidizing everyone else, it's really easy to forget that you had an equal chance of failing if someone was to underwrite you. You're like, why am I paying so much back to this original capital provider? I hate being locked into this deal. But that deal was theoretically whatever the market clearing price was in order to take the risk on you as a young startup, author, or artist.

Near the end here, they are of course referencing the more general Pareto principal that is often associated more closely with VC investing19, rather than investing in general, but I would contend that it does apply more broadly. This dynamic also reminds me of Big League Advance (a private equity investment of Murray Stahl’s).

Earlier in the episode, re. how record labels treat these artists they are signing, the hosts mention…

They're trying to capture revenue even if they're not helping you create the album and you're over-producing revenue on your own on their side. They're like, oh, we're your label so we're involved in everything your brand does.

… Sounds a lot like owning equity as a passive investor (in the right / properly aligned companies), doesn’t it?

Then, on why the industry isn’t fair…

[I]n order for these terms to truly be market price, you need the labels to not be making a ton of profit. If they're very profitable on a free cash flow basis, all the way, full bottom line, if they're printing money, then what you can say is, jeez, is this an oligopoly? There are only three people here, so there's not actually a good competition among the people that want to give you money as an advance in order to do all the stuff that a record label does. These businesses aren't that good of businesses, but… It's an oligopoly. It's an oligopoly.

So, to even more closely replicate this model in your portfolio, this is perhaps a message to go for the niche, illiquid, and pessimism-fraught areas —ie. where there is a lesser supply of other “labels” and capital looking to “sign” those “artists.” Like I mention at the end of the previous section, selecting stocks that are presently outside or ignored by the fund flows of the global passive/index investing complex may also be a good way to reduce systemic risk.

While the hosts spend most of the episode pulling for the underdogs —Taylor Swift and the other artists under the record labels— they do acknowledge the value created by the music labels and their aggregating of risk as well…

I think, in the same way that we would need to—throughout this entire episode—advocate for the rights of the artist and the person really creating something that people love, there is also real value in the world and taking a chance on someone. That doesn't mean you [should] have infinite upside from taking a small chance once, but it is worth recognizing that this was a risk.

… Note that, with equity investing, rightly or wrongly, the upside really is unlimited.

In defense of degeneracy, junk food, and strategic drift… (or simulated annealing, as I call it)

On the subject of occasionally buying and slowly accumulating a variety of small positions that could be considered moonshot, nonsense investments, perhaps highly risky / speculative: you may call it degeneracy, but I call it simulated annealing. For this category, I like to be able to check something like dataroma and etf.com and check that very few high-profile funds/investors hold the stock and that only a small minority of total shares are held by any indexes.

Simulated annealing is a machine learning concept that is used to find the best solution to a problem by mimicking the process of annealing in metallurgy. Annealing is a process by which metals are heated and then cooled slowly to create a structure that is more uniform and stronger. In simulated annealing, we start with a random solution and then slowly make small changes to it. We then compare the new solution with the old one, and if the new solution is better, we accept it. If the new solution is worse, we may still accept it with a certain probability, which decreases over time. This process of accepting less optimal solutions with decreasing probability allows us to escape from local minima, which are suboptimal solutions that we may get stuck in if we exclusively accept ever-improving solutions. This may seem counter-productive, but I will explain a bit more…

Let’s say we have a large two-dimensional cross-section of rolling hills and we want to find the lowest point of elevation in the area. We could use simulated annealing to solve this problem. We can attempt to find the global minimum of an error function by starting with a high point and randomly sampling nearby points. As the error values we sample decreases, the probability of moving to a worse solution decreases, allowing the algorithm to converge to the global minimum.

In our example, we could start at a random point on the map and use simulated annealing to find the lowest point. At high points, we would randomly move to nearby points on the map, regardless of whether they were lower or higher in elevation. As the elevation declines, we would gradually reduce the probability of moving to a higher point, allowing us to converge to the lowest point on the map.

Simulated annealing is a useful technique for escaping local minima because it allows the algorithm to explore the search space more broadly, rather than getting stuck in a suboptimal solution. By gradually reducing the error, the algorithm can focus more on exploiting the best solutions it has found, rather than continuing to explore new areas of the search space. The Nifty-Fifty referred to a group of highly regarded stocks in the 1960s and 1970s that were believed to be “one-decision”20 stocks that seemingly offering guaranteed growth and stability until their prices were brought back to earth in the 1973 recession —today, the majority have been acquired by competitors or have gone bankrupt. The fate of the former Nifty-Fifty are a testament to the value of continually finding ways to break from the norms of any given period.21

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos has talked repeatedly about the value of a culture of experimentation, nimble iteration, and getting in reps of shots-on-goal; even the iterations through the various phases of Warren Buffett’s investing career were characterized by high portfolio turnover22.

“I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment. Most large organizations embrace the idea of invention, but are not willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there. […] In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate, you can score 1,000 runs. This long-tailed distribution of returns is why it’s important to be bold. Big winners pay for so many experiments.” —- Jeff Bezos, “Amazon.com, 1997 Letter to Shareholders”

… In a coffee-can strategy, I’d perhaps limit this category of investments to 5-10% of a portfolio (with, say, a 1pps maximum position size per stock); a small but important portion of the portfolio dedicated to little experiments that could have significant payouts.

The closing comments on this video about the trails and tribulations of ants —in particular, death spirals— I think are quite relevant here:

An experiment

I’ve allocated a significant portion of my own money aside for testing a version of this strategy over the course of the next few years and may make posts for periodic progress updates. I have injected a significant cash allocation into a secondary portfolio and will be slowly allocating 2-3pps per position into various dividend-paying stocks (with some allotment for small non-income generating bets) over the course of the next 12 months across a broad swath of sectors up to at least 50% of the portfolio —the remainder of the cash will be held in a money market fund for the time being where interest income can be used to fund further incremental investment; staggered in this way to allow for even better opportunities to show up in time. I plan to sell nothing out of this portfolio —one of the reasons for the cautious pace of my dollar cost averaging plan— and allow self-ordered criticality to allow the winners to rise in the fullness of time.

I currently plan to use it as a secondary account to use to make charitable donations via some portion of the income it generates each year (the remaining income being reinvested into new positions or money market funds, given the that interest rates are currently reaching decade highs, though “real rates” are still negative) as a way to avoid the headache of having to go through all my bank statements each year to find all of the scheduled donations I make across the each month of the year when filing my taxes; this way I know the exact amount on a single, specific bank statement. This also allows me to dollar cost average that cash, that otherwise be donated each month, towards investments that can compound and generate further income into the future. I plan on doing regular annual or semi-annual updates on this portfolio going forward.

An aside on dividends vs buybacks and selling shares

“[A]t some day, a financial asset has to give you back cash to justify you laying out cash for it now. Investing is the art, essentially, of laying out cash now to get a whole lot more cash later on, and something at some point better deliver cash.” ~~~ Warren Buffett (1998, https://buffett.cnbc.com/video/1998/05/04/morning-session---1998-berkshire-hathaway-annual-meeting.html)

“““

Me: Could management give a bit more detail on what would entice them to make dividend distributions to FRMO shareholders? On the point regarding Mr.Bregman's comments on stock dividends for investors to create a home-made custom dividend yield opposed to cash dividends from the company and also relating to the gentleman's question on FRMO's valuation near the end of the previous meeting, I'd just like to say that: 1] I would like to retain as much relative percent interest as possible in the business of FRMO itself for as long as possible and 2] I would like any gains received from my ownership of the business to be based on the economics of the underlying business rather than the vagaries of Mr.Market and whatever the market price and liquidity happens to be on offer in the market at any given time.

As the gentleman in the previous meeting notes, the valuation of FRMO by Mr.Market does not always make perfect sense. I'd like to repeat the Warren Buffett quote that “I never attempt to make money on the stock market. I buy on the assumption that they could close the market the next day and not reopen it for five years.” From this perspective I completely understand management's continued apparent deprioritizing of uplisting FRMO; it has nothing to do with the fundamental operation of the business.

With a cash dividend, the economics of the business or underlying owned businesses of FRMO can speak for themselves and could, in a way, reduce or eliminate the need for any kind of uplisting, re-rating, or other form of greater recognition from marginal buyers in order to reward existing shareholders, in this case rewarding existing shareholders for inching towards becoming ex-shareholders. This would also allow existing shareholders who are not directors to continue opportunistically accumulating shares without having to compete with any newer segment of Mr.Market that any road show may gain the attention of.

Murray Stahl: Okay. So the moment I agree with all, by the way, I agree with all the sentiments in the question. So I'm completely in agreement with all that stuff.

“““ —- FRMO FY2024Q2 earnings call (UPDATE 20240123)

Note that because of the goal of using a portion of this portfolio for charitable giving, it will necessarily need to generate cash income and thus will be mostly restricted to dividend-producing securities —with the exception of some ‘simulated annealing’. In a way, this means that I’d have to seek businesses that do not (at least consistently) have opportunities to redeploy all of their cash at attractive incremental returns on capital —again, OTC Markets Group comes to mind here.

At the very least, I like dividends as a bit of a heuristic that hint that the CEO is not simply interested in empire-building.

I’m banking on dividends here because I don’t really like the “sell-off” alternative to income generation from a portfolio where buybacks are used to increase the value of each share and then investors are expected to sell off their shares in the business in proportion to the amount of income they would like to withdraw from the business. This “sell-off” idea is mentioned by Buffett in the sections covering dividends and dividend policies of Lawrence Cunningham’s “The Essays of Warren Buffett”:

These earnings may, with equal feasibility, be retained or distributed. In our opinion, management should choose whichever course makes greater sense for the owners of the business. This principle is not universally accepted. For a number of reasons managers like to withhold unrestricted, readily distributable earnings from shareholders-to expand the corporate empire over which the managers rule, to operate from a position of exceptional financial comfort, etc. But we believe there is only one valid reason for retention. Unrestricted earnings should be retained only when there is a reasonable prospect-backed preferably by historical evidence or, when appropriate, by a thoughtful analysis of the future-that for every dollar retained by the corporation, at least one dollar of market value will be created for owners. This will happen only if the capital retained produces incremental earnings equal to, or above, those generally available to investors.

You can see Buffett speaking on this issue here:

IMO, dividends have the added benefit of making ‘real’ any positive economics of a business in a way that is agnostic of how Mr.Market may be pricing your shares at any given time as opposed to relying on the market to 1) be open and available with enough liquidity and 2) favorably price your shares at the given time that you may want to sell shares for income purposes (i.e. requiring you to time the market) as Buffett proposes and has done with his Berkshire stock for the purposes of charitable giving. Until I’m actually getting cash in hand from my investments, they’re just numbers and charts on a computer screen that the market’s marginal buyers/sellers can write down at any time.

In Buffett’s own words, from the 1979 Berkshire annual letter:

“The reasoning of managements that seek large trading activity in their shares puzzles us. In effect, such managements are saying that they want a good many of the existing clientele continually to desert them in favor of new ones —because you can’t add lots of new owners (with new expectations) without losing lots of former owners.”

… yet that’s exactly the logical consequence of relying on the sell-off method for custom, home-made “dividends” that Buffett advocates shareholder do with BRK stock. Unless of course you don’t actually care about getting cash back from your investment and just want to see the number on your brokerage computer screen go up.

Would you start a business just to watch the equity value go up with only the goal of eventually finding someone to selling it off to —and not even taking a salary at any point along the way? Maybe I’m alone here, but I wouldn’t. And I wouldn’t buy a business to do the same either. Maybe I just don’t like the zero-sum aspect of buying businesses with the idea of only profiting from selling them off to someone else at a higher price. I want to have to care 0% about what Mr.Market is going to think of the situation when it comes to how I’m going to get rewarded for owning a business in the longrun.

Value of cash = Value of cash =/= Buybacks = Whatever Mr.Market says it’s worth.

Unless I think the stock has a good chance of eventual multi-bagger potential, one way I think about this is, rather than coming from the POV of “what will my portfolio value or that individual position look like in 5-7 years if the stock performs well?”, I think about “what will my incremental recurring income look like in 5-7 years if the business is executing in success mode?” I usually don’t have a hard number in mind, but I want it to at least be higher than what I have, presently, and significantly higher than the real inflation rate. I assume that if the company can sustainably grow it’s FCF/sh over time (and can distribute it in some proportional way), then the DCF and capital gains will take care of themselves.

.

My theory on why Buffett espouses this buyback-dividend-equivalency idea, despite its many conflicts with reality, is because of the fact that the amounts of capital he works with are so large that the liquidity of the kinds of securities he normally invests in would never be an issue (vs certain OTC or otherwise thinly traded stocks I may own). It is also very possibly because he is simply addicted to investing and wants to keep the dividends to himself and remain more directly involved in their reinvestment; I don’t think this should actually be very hard to believe or is necessarily a bad thing for shareholders.

Unless management has made a good case for a company’s shares being highly discounted vs fair value, I’d rather just get capital returned as a dividend and let the business’s FCF and yield speak for itself and let Mr.Market re-rate the stock on it’s own. But buybacks as a preferred return-of-capital mechanism just for tax purposes (even when a company’s stock is trading at or above fair value (if management is even thinking about value when deciding spend on buybacks))? No.

********** UPDATE 20230923: I was recently skimming across the highlights and scribbled notes in my copy of Lawrence Cunningham’s “The Essays of Warren Buffett” and got to the section on Buffett’s commentary on Berkshire’s listing on the NYSE and discussion on shareholder appeals for a BRK stock split (Chapter III in the 8th edition). Perhaps the reason that buybacks have a great equivalence to dividends in Buffett’s mind is because Berkshire is explicitly managed in a way that is intended to —among other things— attract shareholders that “think and behave like rational long-term owners” and to encourage the rational trading of the stock “in a narrow range centered at intrinsic business value (which we hope increases at a reasonable —or better yet, unreasonable—rate)”; perhaps these are the only kinds of companies that one should invest in. If this kind of behavior were the case in the wider market, which I don’t think anyone seriously believes, then indeed Mauboussin’s assumptions in his dividend-buyback equivalency ‘proof’ would indeed comport with reality. (Though as I mention later in this post, even in a totally rational market, realizing an equivalent dividend yield from buybacks is not always possible at certain unit stock prices and position sizes). **********

.

A cash dividend also has additional value to a shareholder from its optionality; you have the option to reinvest, reallocate, or even take that out and finance your Costco membership, groceries, or a little date night….

… The cost to a shareholder being the associated taxes —which can be reduced to the same amount as the “sell-off” method if you simply hold the stock for the long-term such that the dividend is “qualified” or in the case of “special” dividends23— and the opportunity cost being that the business you own is unable to reinvest that portion of cash flow on your behalf towards growing their own operations; maybe that’s not so crazy…

In Mauboussin’s 2022 “Capital Allocation” paper, he recalls an interesting mental experiment by, economist and financial historian, Peter Bernstein in which companies disburse all of their earnings to their shareholders and then ask the markets for funds to invest as the business comes up with new opportunities —essentially, investors would be able to invest in businesses on a per project basis. His thinking was that since markets are better at allocating capital than companies, overall capital allocation would improve as the result of this check by the capital markets; you can read that full interview here.24 Of course, this would seem to rely on a high level of efficient market hypothesis and reliable equanimity from Mr.Market that I don’t think most people outside of universities believe to be representative of reality.

Taking this income focused POV, me and Buffett do have something in common, we both don’t care too much about the day-to-day stock price —I’d argue myself even less so given that Buffett and his BRK shareholders would still need to rely on those price signals to get an idea of how much he can actually get from the market for his home made “sell off” capital harvesting at any given time. What I care about is longterm yield-on-cost and income growth above the rate of (real) inflation which I find, in itself, encourages one to look at the business on a more fundamentals-based perspective; it drawing more focus to things like economic moat, free cash flow (as you want a dividend derived from CFFO and not from debt or other temporal financing arbitrage), the longterm growth thereof, the efficiency of invested capital, the business/industry’s general WACC trends, and management alignment —vs spending any of my time speculating on what’s going to induce Mr.Market to re-rate a multiple. “Business owners think longer term than renters do.”

In any case, a dividend also acts as a kind of hedge against rising interest rates in that it adds a near-term cashflow component to a security that might otherwise be purely a long-duration one, since you are now receiving cashflows on an on-going basis in addition to the (more uncertain) expectation that you can recieve cashflows further in the future based on capital gains when you decide to liquidate for whatever reason or on the hope of some distant establishment of a dividend policy down the road at a higher yield-on-cost; I’ll take a little bit now at the cost of, perhaps, slower capital appreciation growth from re-investment activities just to create this diversity in duration risk on the stock.

Management receiving certain types of bonuses from a business presents another small thing that makes me look at the situation askance when dividends are absent, since these are forms of distributions tied to the economics of the business (vs Mr.Market’s pricing thereof) that shareholders are excluded from —I get that it can help align incentives, but still… I guess like most things, it really boils to down to “it depends”. At least in this respect, I recognize that the more aligned companies that lack distributions, like Berkshire and FRMO, have management riding in the same boat as shareholders (the latter even more so than the former given that Stahl doesn’t even get a salary as FRMO’s chairman)25. Nor am I a fan of the buyback/distribution equivalency as detailed by Michael Mauboussin, which critically relies on the theoretical assumption that your stock will always trade at fair value and will have sufficient liquidity in the market to sell your shares at that fair value price26 —not to mention the issue of losing your share of the overall business. Maouboussin says as much in “Capital Allocation: Results, Analysis, and Assessment”:

“In reality, the conditions required for equivalence almost never hold. For example, the tax rate for dividends and long-term capital gains is the same for investors who hold shares in accounts subject to taxes, but the amount to be taxed can differ. The full dividend amount is taxed but with a buyback only the capital gains are taxed. Investors who sell shares in an amount equivalent to the dividend, creating a homemade dividend, are taxed based on the difference between the price of the sale and their cost basis for the stock. In non-taxable accounts, the tax issue is not relevant. None of this is tax advice, but we want to point out that tax treatment can create a difference in economic outcomes for dividends and buybacks. Dividends tend to occur on a specific schedule, with most companies paying every quarter. Buybacks are much more sporadic. We also saw that dividends are much more stable than buybacks (exhibit 33). The assumption of identical timing does not reflect how companies actually behave.”

.

I get that buybacks reduce sharecount, but to that end I really only see them as a real return-of-capital if they are —assuming they are even in excess of that period’s stock-based comp dilution— a prelude to increased dividends per share.

.

Homemade, selloff-based dividends are not even always possible if the hypothetical yield from a buyback if the dividend rate is less than the price of your stake (not to mention it's just more work on your part do do this calculation and sell-off every year). Shares of TPL currently trade around $1370/sh and have around a 1% dividend yield. In order to be able to sell off shares to collect a yield equivalent to that of the dividend, if it were instead rolled into TPL’s buyback program, you would need to own $137000 worth of TPL stock (X * 0.01 = $1370 ==> X = $137000) or 100 shares, any lesser amount of shares and your “yield” would be below the value of a single share. Even if you had a $1MM portfolio, you would need to commit to a greater than 10% concentration in TPL for the selloff-based dividend option to be available to you.

A similar situation can be found in the case of Constellation Software (TSX:CSU). The company has distributed an annual dividend of around $85MM has traded at a declining dividend yield ranging from 4% to 0.2% over the last decade due to it’s rising stock price. Through all of 2022, the dividend yield was around 0.25% while the stock traded at an average price of $1569.63/sh. How many discrete shares of CSU.TO would you need to own to have been able to sell off 0.25% of your position that year to actually realize a selloff-based dividend if that distributable cash (FCF available to shareholders (FCFA2S) as Mark Leonard calls it) was used on stock buybacks vs dividend proper?

We want to know the minimum number of shares required to realize the dividend by selling off stock, Rm > 0.

Let Sp be the share price after the buybacks ($1569.63 x (1 + 0.0025)).

Let position size, P = Sp x Rm.

Using the modulo operator from discrete math (which just gives you the remainder of a dividend and divisor), if Rm is such that we can sell of 0.25% of our position in whole stock units, then: (P x 0.0025) mod Sp = 0.

Solving for Rm in this system of equations, we have Rm = 400n where n is a whole number >=1.27 That is, we need a minimum of 400 shares of CSU.TO (which would have totaled $627,852 at the time) to have been able to realize that 0.25% dividend by selling off stock instead (and would need to buy additional shares in increments of 400 in order to increase position size while still maintaining the ability to sell-off a 0.25% yield).

In computer science, this could be looked at as a 0/1 knapsack problem (or subset sum problem) where you are constrained to have the knapsack use all available space; the knapsack size being your desired yield amount (or the yield you’d get if a company’s buyback spend were instead distributed) and each item is weighted by the unit stock price. There’s only a limited range of scenarios where your going to be able to get a perfect fit in this case —and you’d still have to contend with the market actually providing the liquidity to make it work. That is, not all knapsack problems have a perfect, knapsack-filling solution. (It would be another story if you could easily sell fractional shares).

.

If I were forced to extend an olive branch to the sell-off’ers, I’d maybe put it like this: If you plan to hold and do not require (or desire) current income, then buybacks are fine28; if you plan to hold and require current income (i.e. not re-investing distributions), prefer dividends. For the purposes of this experimental portfolio, I require realized income —and have no desire on relying on Mr.Market’s day-to-day sentiment or liquidity to provide that, nor do I want to reduce my share in any of the companies that I plan to coffee can and allow the Taylor Swifts of the bunch to emerge from.

But no matter what, I will say this: The mindset should be that yield —not capital gains— better come eventually, else you’re just playing an online multiplayer video game of find-the-greater-fool.

Like Buffett himself says:

“I never attempt to make money on the stock market. I buy on the assumption that they could close the market the next day and not reopen it for five years.”

It should be noted that Buffett has a sizable private portfolio that generates income for him outside of Berkshire.

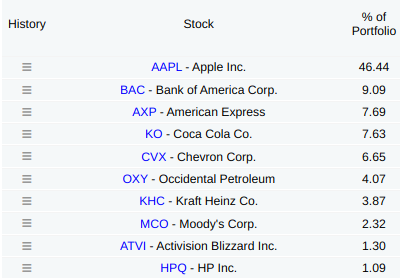

********** UPDATE 20230715: Note that, with the recent exception of Activision Blizzard starting around 4Q2021, every stock in Berkshire’s own top ten holdings pays some kind of dividend (usually around a 3-4% yield). Do you want to do as Buffett says or do as he does?

While Berkshire Hathaway itself does not pay a dividend because it prefers to reinvest all of its earnings for growth, Warren Buffett has certainly not been shy about owning shares of dividend-paying stocks.

Over half of Berkshire's holdings pay a dividend, and several of them have yields near 4% or higher. —- https://www.simplysafedividends.com/world-of-dividends/posts/4-warren-buffett-s-dividend-portfolio

**********

********** UPDATE 20230914: I think a stock-dividend —as put forward by FRMO co-founder Steve Bregman at the 2023 annual shareholder’s meeting in response to my question re. a future dividend policy at the company— could be an acceptable compromise if companies would distribute fractional shares, though this would still put those shareholders desiring actual income from their investment at the mercy of Mr.Market’s sentiments at any given time —certainly a concern for FRMO which trades on the OTC Pink ATS tier. **********

“In 18th and 19th century England, someone’s wealth was not quoted in the value of their stocks, bonds and the equity value of their homes, as it is today, but on the income their capital earned. In the opening pages of Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice, a wealthy young man’s fortune is described as “four or five thousand a year.” That was the income produced by his capital.” —- Steve Bregman, HK FY2024Q4 Commentary ********** (UPDATE 20240208) **********

TBH, from the letter, it’s unclear if Buffett means that these dividends attracted shareholders to price the stock upwards, if the dividends were a byproduct of success in the business, or if the reinvestment of the dividends were what increased the size of BRK’s Coke and Amex investments.

Interestingly, when I was doing a bit more reading to flesh out some ideas before writing this post, I found that there are a lot of references implying a bout of popularity of this strategy in India (in the Indian blog post here for one example), spurred by the publication of “Coffee Can Investing: The Low Risk Road to Stupendous Wealth” by Saurabh Mukherjea (February 1, 2018), which is also referenced in this Indian paper published in the International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications; the book was published just a few weeks before Chris Mayer’s “100-Baggers” (May 22, 2018), which is where I myself first heard of this specific term. Of course, both books —and the research paper— give ultimate credit to investment manager Robert Kirby for coining the term.

This 63% number from MorningStar’s Michael Laske is widely cited, yet I could not find a primary source for this, TBH.

Charlie Munger actually mentioned this in the recent Berkshire 2023 annual meeting…

An interesting fact that he [Graham] was sheepish about in his old age was that more than half of the investment return he did in his whole life came from one stock; one growth stock, GEICO, [a] Berkshire subsidiary. At the time he operated, there were a lot of sorta lousy companies that were too cheap; you could make a little money floating from one the other; the big money he made was [from] one growth stock. Buying one undervalued great company is a very good thing as Berkshire’s found out again and again.

Turkeys often stick their necks out too far and get their whole heads cut off to feed the (volatility) farmers.

The commentary also includes a brief section on investor John Templeton that has very similar themes as this buy-and-hold, emergent-strategy method discussed by Bregman which I was going to incorporate into a section in this post specifically dedicated to Templeton, but I think the HK commentary on his investing career here is sufficient for our purposes.

So a portfolio set up this way would have initial position sizes of 2.85%. This is really more just a note for myself as it relates to something I mention at the end of this post.

I don’t believe any re-balancing was done during this backtest.

Interestingly, a portfolio that was annually adjusted to be equally weighted in all stocks that comprised the index —i.e. added stocks that made the index and removed stocks that fell out of the index— for that year outperformed the actual, marketcap weighted, index during the backtest, 24% to the S&P 500 index’s 20% annualized return over the period.

https://twitter.com/chriswmayer/status/1660003110754963456?s=20,

https://us13.campaign-archive.com/?u=6dc62f307511d466ff78a94fe&id=aa85a613a1,

I could not find a primary source for this article on Verdad’s actual research library, https://verdadcap.com/weekly-research

There’s also the interesting feature that the CRSP idea of “investability” includes a requirement for total floating shares (total shares outstanding less any restricted shares, which are defined as those held by insiders or stagnant shareholders including, but not limited to: board members, directors and executives; government holdings, employee share plans, and corporations not actively managing money) to be at least 87.5% of total shares outstanding, so very tightly owned public company would have to see insiders getting rid of their shares for it to be added to the index, yet this seems like a signal that would indicate that this is the precise time that investors might want to be wary of investing in the business. This kind of extremely-low-float situation isn’t something I see come up very often, but I just thought it was interesting.

(https://crsp.org/files/crsp-market-indexes-methodology-guide.pdf)

Furthermore, the Vanguard ETF itself uses the “weighted average price/earnings ratio of the stocks it holds” to determine the P/E value displayed on the ETF’s web page. I wonder if this is accounting for any of the component stocks that may have negative P/E ratios? That is, what is the reciprocal of the earnings yield of the ETF if calculated by summing all the index-weighted earnings of the composite stocks divided by the total market cap of the index? Would this give a higher or lower P/E?

Though there’s always poison pills, dual class share structures, and onerous shareholder agreements (as Murray Stahl and Eric Oliver are dealing in TPL with as I write this)

From the interview: