Lessons from Murray Stahl

Contrarianism, convexity, and the power series of coffee cans and art dealers

After reading more of the FRMO letters and other content by Stahl for my previous post…

… I thought some of Stahl’s views were pretty interesting and fortunately he’s a rather prolific publisher of content —maintaining a “writing culture” at his asset management business, Horizon Kinetics (HK) (you could also think of it as a form of content marketing for his business)— and tends to be fairly candid during shareholder meetings. I find that he has a Steve Jobs “reality distortion field” effect almost every time I listen to him answer the pelting of questions during the shareholder meetings. Given all this material, I decided to make a few notes on some of the takeaways I’ve gotten from reading a good bit more of his writings and transcripts. Some of these notes are pretty standard stuff you can take away from reading many other successful investors, while others are a bit more specific to Stahl.

(Fact-based) contrarianism and rational iconoclasm — If people hate it, that’s your opportunity

“The philosophy is that if people hate it, that’s really your opportunity set. It doesn’t mean that they’re wrong to hate it, but if everybody thinks it’s wonderful, for me at least it’s not an opportunity. I leave it to other people because I’m not going to learn more about it than they already know,’ he says. ‘If millions of people are following something, it might be a great investment but I have nothing to add.”, https://citywireusa.com/professional-buyer/news/if-people-hate-it-that-s-your-opportunity-inside-murray-stahl-s-crypto-calls/a1102710

“Generally speaking, our philosophy is to do things that other people are not doing. We believe that the efficient market hypothesis is usually valid. If you want to find a good investment, meaning a good business or company, you are unlikely to uncover information or devise an analysis that other people do not have. The only time you get a “deal” is when you invest in a company that people do not know well or avoid because of a structural anomaly or a structural constraint [which I read as “non-economic” reasons / reasons other than the actual fundamentals of the company itself per Joel Greenblatt’s YCBASMG or Maurece Schiller’s Investor’s Guide to Special Situations (though Stahl’s current bets on BTC and TPL are not totally in this sphere)].”, http://csinvesting.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Kinetics_Market_Opportunities_11.02.2016.pdf

[I]t is a fact that very much of the time, particularly when the preponderance of investors moves toward an extreme, fact-based investing looks very much like the opposite of the market. It might look as if it’s contrarian by intent, but that’s only an outcome – an outcome of investing on the basis of information, as opposed to momentum or arbitrary index weightings or unqualified growth presumptions and other crowdbased investing approaches., https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q3-CVALUE-Review_FINAL.pdf

“That which you most need will be found where you least want to look.”, Carl Jung

Stahl’s contrarianism is about seeking games where he has a higher likelihood of finding an edge, which in this case just means fishing where the crowd is thinner. It’s a simple and common value investment adage that often proves psychologically difficult to follow, but Stahl has apparently been able to maintain this discipline. He’s invested heavily in the much-hated oil industry through his concentrated TPL position held since the 90s and continuing beyond the 2014 oil crash —which TPL’s stock price was able to ride out with relative ease1— into the present era of heighten institutional ESG fossil fuel hostility, as well as investing in the much-mocked Bitcoin and cryptocurrency space while it was still relatively unknown early in 2015.

Stahl has also been a critic of the saturation of indexation in the stock market for a long time as well. (However, it should be noted that most of HK’s asset management business was historically through active mutual funds that are directly negatively affected by the rise in indexes and ETFs —so he’s not exactly a neutral observer here). One way to avoid crowded games is to look to stocks and markets that do not (yet) have a place in any major indexes. In a section of a 2017 HK commentary titled “Be Outside the System - It’s OK to Earn a Return a Different Way”, HK co-founder Steve Bregman had this so say:

These issues of market saturation and valuation apply to substantially all of the major index‐centric stocks that represent ‘the market’ as investors understand it, including the consumer branded products companies like McDonalds and Procter & Gamble. Indexation has unwittingly become the place to go for systemic risk. Whether the index constituents are designated as consumer discretionary or information technology, or as dividend aristocrats or REITs or Non‐US Developed Nations, their practical capacity to provide differentiated outcomes has been largely drained away. The diversification exists primarily in name only. […] The large‐cap and mega‐cap companies occupy the same multiplicity of ETFs and experience the same inflow of funds upon which they largely depend for their valuation. As they do upon artificially low interest rates. They have either substantially saturated their markets and cannot expand their sales, in which case they trade at P/E ratios traditionally reserved for growth companies, of 22x to 25x; or they manifest legitimately rapid growth, in which case their P/E ratios are so anomalously high that they are actually excluded from the index P/E calculations. Under these circumstances, does the safety of the crowd, herd immunity, still pertain? If the primary risks are systemic, then perhaps one should be outside the system. No one requires you, many of us are driven to remind our teenage children, to stay at the party if you’re uncomfortable being there.

Looking ‘outside of the system’ in this way, you have a greater field from which to find investments that are (continuing the above quote) “quantitatively superior in terms of low valuation and/or lower risk and/or higher price optionality. They are functionally, not just semantically, diverse in terms of the economic factors that will determine their success or failure; each has the capacity for positive performance independently of the market in a way that can’t be replicated by an index‐centric stock.”

********** UPDATE 20230318) From Stahl himself from the 2022 annual shareholder meeting:

An index doesn’t even see valuation, it’s not in an algorithm. If you remove the active managers, how can the market be as efficient as it once was? Therefore, the market has to assume a certain amount of inefficiency, maybe not with regard to every security, but certainly in sectors. And that's what we've found at Horizon Kinetics. There are all sorts of pockets of opportunity. […] The structure of passive management is that capital or money flows in accordance with a preordained formula, the indexation formula, which is that the weighting of the companies is based on market capitalization, adjusted for the float. As a generalization, the money is flowing to the largest, most liquid companies.the indexation structure guarantees that funds will flow to those enterprises least in need of capital, to the big companies, while funds will not flow to those companies that actually need it. That means that all sorts of things that could be developed or built, which presumably could serve human needs in society, are not being served. Ultimately, that misallocation of capital creates problems in society. One of those challenges we've managed to exploit these last couple of years is in the energy sector.

**********

More broadly, this may be related to the quote from Seth Klarman in his book “Margin Of Safety” where he says that “ample investment opportunities may exist in the securities that are excluded from consideration by most institutional investors. Picking through the crumbs left by the investment elephants can be rewarding.” This reminds me of what Stanley Druckenmiller has said in the past on how liquidity is what moves markets:

“Earnings don't move the overall market; it's the Federal Reserve Board. Focus on the central banks, and focus on the movement of liquidity. Most people in the market are looking for earnings and conventional measures. It's liquidity that moves markets”

From this POV, the areas of opportunity generally come from the illiquid and thinly traded ares of the stock market.

This also kinda reminds me of the volume-focused- and technical-analysis-based perspective of another little-known investor, Ted Warren.

“Warren advises his readers to study long range stock charts to select favorable entry and exit points, he also asserts that the stock markets and individual stocks are subject to manipulation by various unnamed financial interests and that you should profit by observing their actions rather than lose by being unwittingly subject to them. If I had to throw away all my investing books apart from one this is the one I’d keep.” —- Elementary Value

Of course, being contrarian is not truly about being opposite —though tending in that direction does often reveal uncrowded or misinterpreted opportunities— but rather about thinking independently. I go into this a bit more later.

Concentration

“Diversification is a risk control measure, but do you really reduce risk by investing in areas you know nothing about? For example, a biotechnology company, which works on a cure for a disease, may or may not succeed. I do not have the expertise to determine the outcome. I believe it is much better to concentrate the investments where my critical understanding would play a role and where I can find something with investment merit, not just conjecture.”, Murray Stahl http://csinvesting.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Kinetics_Market_Opportunities_11.02.2016.pdf

Looking at the Horizon Kinetics (HK) mutual funds (of which Stahl is the Chief Investment Officer), you can see that they have active share ratios, which measure the percentage of stock holdings in a manager’s portfolio that differs from the benchmark index, of around 90% (and have about 50% of AUM concentrated in the top 3-5 positions for any given fund).

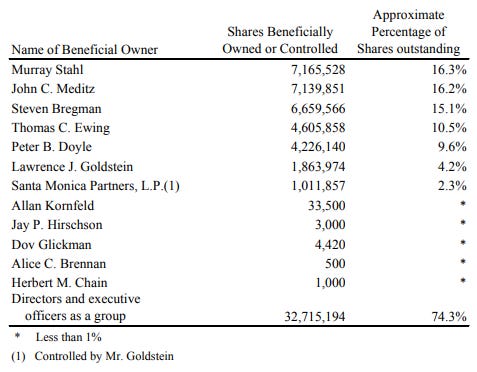

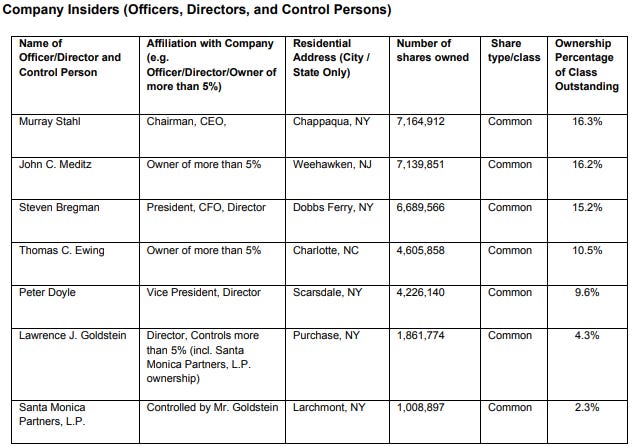

This concentration is also evident in FRMO’s own investment concentration that is currently 45% TPL and 15% GBTC relative to total book value. Both of which have contrarian and structural-impediments-to-ownership characteristics: TPL for the various ESG-driven industry financing difficulties and long term industry underinvestment themes outlined in various HK commentary and GBTC for the technical and regulatory difficulties for institutions wanting to own BTC2, in addition to the general hatred of the asset by many very-smart-investors, certainly around the time that Stahl started buying BTC (which was around the same time as another legendary investor Bill Miller). (To be fair, those opposing very-smart-investors may still turn out to be right).

Note that this concentration is not quite the same as Nick Sleep’s big betting style, but rather something that gets built up over time from rather small positions where winners are simply allowed to run. I’ll go into this a bit more later.

History, autobiographies, and the game-tape of life

“Instead of just reading about someone who made a lot of money, I became addicted. I’d read anything [biographies / autobiographies] – anybody who did anything. It didn’t matter. They could be a cook, they could be a soldier, I didn’t even care. I just wanted to hear their story [...] Whatever problem you’re having, you're not the first person to have that problem – you're about the six billionth person to have that problem. So the first thing is you want to read about people that have similar experiences to you and find out what they did. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Some of their advice will be useful to you, some of it will not [...] You can meet a great many many more people through autobiographies. They can tell you about their mistakes and you can learn from them. (Only an idiot learns from mistakes, smart people learn from other peoples’ mistakes, Otto von Bismarck)”, —- Murray Stahl on biographies and autobiographies (beginning and end of the interview)

Before I even look at a financial statement, I try to find out as much as I can about the history of the company, to understand how it has arrived at its current predicament. (If we’re looking at it, it’s usually a predicament.) I’m trying to find evidence of similar issues in the past and what happened, to help judge whether current problems are controllable and rectifiable. —- Murray Stahl, 11.21.07 (from The Art of Value Investing, Whitney Tilson)

“I have one little hobby that I’ll share with you on this point. I like to collect and read newspaper magazine articles many years after they’re published. With the benefit of hindsight, I find it very interesting and to some degree amusing.”, —- FRMO 2019 annual shareholder meeting

“History is the most reliable path to understanding the present and anticipating the problems of the future.”, —- Will Durant (Lessons of History)

While Stahl’s bachelors degree is in computer science, he also has a masters degree in history and was obsessed with reading auto/biographies during his college years and into his time with his place of employment before founding HK, Bankers Trust Company. He wrote a book about successful people throughout history, though it’s hard to find any existing copies of this. See…

… which he also mentions here: https://player.captivate.fm/episode/3d0751dd-7577-450f-ad3a-1572264796e6?t=190. (Given the open-ended way the FRMO conference calls go, I should ask management if they could release a digital or reprint of this book again sometime).

********** UPDATE 20240205: I got a copy of this book in 2022 by asking the HK central office for a copy (I assume you need to be a shareholder of an HK fund or related entity (eg. FRMO))

**********

One resource that would be a more easily accessible and voluminous substitute for extracting (general) ideas from auto/biographies would be David Senra’s Founders podcast, linked to below. I think he does a very good job of extracting and covering key insights from accomplished historical figures, while weaving in enough (but not too much) contextual and story drapery to help allow those insights to be better encoded into the caveman, story-driven brains that evolution has given us3. (Note that he can get very excited about certain actions/decisions/figures, hyping up with a kind of survivorship bias certain aspects that seem either banal or counterproductive, but if you just know that going in, the episodes are overall very enjoyable).

A similar interest in history to Stahl’s has been expressed by the likes of Howard Marks, Marc Faber, and many others; draw any highly successful person’s name from a hat and they will likely have a deep knowledge of history (though it may be highly specific to their area of interest or expertise). What Stahl and many others have done here is essentially reviewed the “game tape” of life so that they could play better.

This interest in (auto)biographies is interesting in that it has a similarity to Charlie Munger’s mental models…

“What you need is a latticework of mental models in your head. And, with that system, things gradually get to fit together in a way that enhances cognition […] The models have to come from multiple disciplines—because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department”

… but encoding these mental models and experiences in a way that seems much more fitting to Stahl’s diffuse and rhapsodic way of speaking and writing4. (Another way to describe his talking pattern may be: (almost overly) meanderingly rhizomatic). I’ve tended to take this as a sign of greater cognitive agility (rather than any lack of focus).

Dalio tends to think in terms of interconnections rather than linearly, which can lead to rambling answers, as he readily acknowledges, “I see things in complex ways, and I have a problem communicating my way of seeing to others.” ~~~ Jack Schwager, “Hedge Fund Market Wizards”

Independent analysis and the scientific method

********** UPDATE 20230616: I think that this story recalled by “100-Baggers” author Chris Mayer is a good way to get into the right head-space for this section:

Lee liked to say facts stay with what you observed, whereas inferences went beyond that. He tells a great little story about Charles Eliot, who was a long-time president of Harvard:

Eliot entered a crowded NY restaurant and handed his hat to the doorman. After lunch, he goes to leave. As he came out he was astonished to see the doorman promptly pick out his hat from the hundreds that were there and hand it to him.

“How did you know that hat was my hat?” Eliot asked.

“I didn’t know it was your hat, sir,” said the doorman.

“Why, then, did you hand it to me?”

And the doorman very courteously replied, “Because, sir, you handed it to me.”

President Eliot was delighted with this precise delimitation of what the doorman saw and what he assumed.

Be humble and careful about what you think you know and what you assume.

(Or perhaps this is really just a trite musing on how explicit facts and implied inferences are muddled together in language)

**********

In this On The Brink podcast episode, Nic Carter interviews Horizon Kinetics analyst (and PM of HK’s INFL 0.00%↑ Inflation Beneficiaries ETF) James Davolos. Davolos talks about his early interactions with HK’s founding partners; he praises the founding partners (Stahl, Bregman, and Doyle) for their original thinking and mentions that they do not tend to rely on outside secondhand reporting to get their information, rather going to the source documents to learn and reach their own conclusions.

We can give some context to what Davolos is talking about here by looking at an interview Murray Stahl did with Ticker. When asked about his research process, Stahl had this to say:

“We write reports on our findings to be able to have a meaningful discussion on the investment. Writing takes time, but there is no other way of bringing people to your level of knowledge, so that they can read and critique your ideas.

Some time ago I considered the devil’s advocate approach, but after reading Jeremy Bentham’s Handbook of Political Fallacies, I decided not to do it, because someone mastering the techniques of logical argumentation, paradoxes, and phrases that unnerve your opponent, could actually win a debate, without necessarily arguing for the right decision.

Instead, I chose the non-adversarial, collegial approach and the scientific method. In science, the way to confirm or reject a discovery is through objectively reproducing the experiment. If someone says he can initiate a nuclear chain reaction, he puts it on paper and someone else follows the same process to see if he gets the same answer. I think the scientific method is much better because it is a cooperative, not an adversarial process. It leads to a better working environment, better idea sharing and, ultimately, to a better conclusion.

When somebody presents a paper with data and logical conclusions, someone else has to examine and validate the presumptions. […] Basically, you gather the information in a way to supplement the analysis, to look at the problem in a different way and gather information from different sources to see if the conclusion is valid.“

The value of this source-seeking and falsification mentality5 can be seen in the story of Horizon Kinetics’ early Bitcoin adoption/bullishness in around 2015 where, as Stahl tells it, he had heard about cryptocurrency/Bitcoin in the news but never really gave much thought on the mainstream debate one way or another until he finally sat himself down and read —among some other resources— the Bitcoin whitepaper and ultimately ended up making HK’s initial call-option-sized bet on Bitcoin.

I don’t feel that I am going out, even a little bit, on a limb in saying that one mental model is the most important. It is, of course, scientific rationalism (or, alternately, the scientific method). This mental model catapulted humanity from centuries, indeed millennia, of slow progress, into rapid and open-ended growth in knowledge and wealth, in a period of a few decades, during a period we now call the Scientific Revolution, or The Enlightenment. The scientific method is based on conjecture and falsification. In plain English: you make a guess, and then try to prove it wrong. If you can prove it wrong: congrats! Your theory is wrong. (On to the next one.) But if you can’t prove it wrong, and others can’t prove it wrong, and it fits the data and is not easily varied, then maybe your hypothesis – your conjecture, your guess – becomes the best theory for the time being. Notice I didn’t say that your hypothesis is proven “right.” The idea that we can never be certain about our theories is called fallibilism. —- Maran Capital Management, “The Most Important Mental Model”

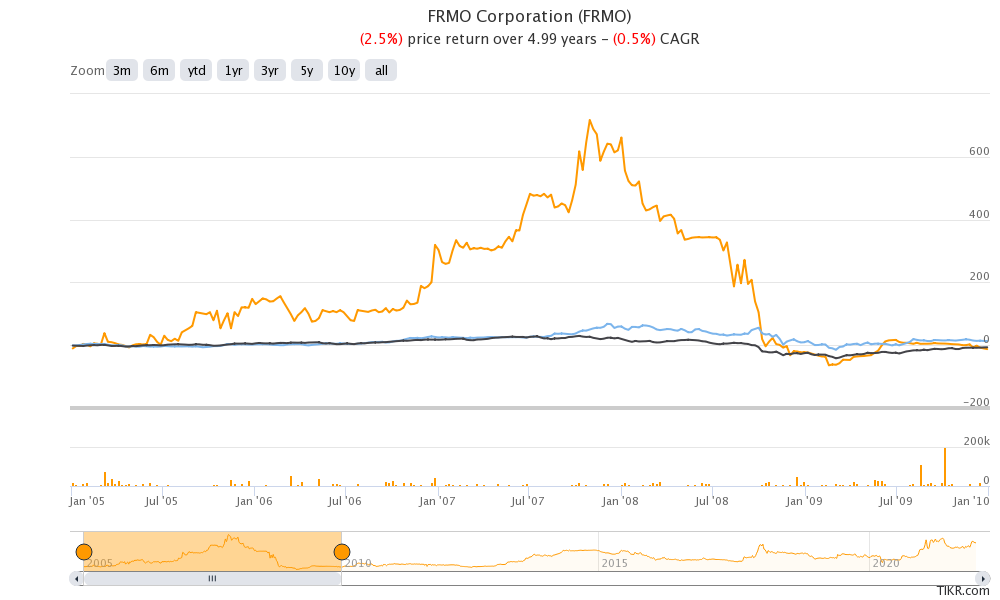

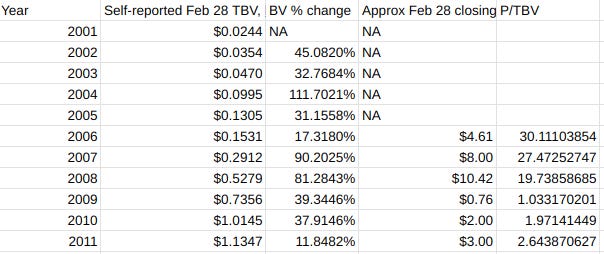

In the Dare To Be Great memo from Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks, he highlights the fact that above average results can only possibly be achieved by doing unconventional things. The independent thinking and research mentality from Stahl has placed FRMO in the top right corner of the outcome/behavior table —unless you simply hate Bitcoin and think FRMO’s now 15% holding is fundamentally destined for zero— w/ FRMO’s CAGR beating the S&P500 by 2pps/yr starting from 2005 to today for a 390% total return vs the S&P’s 240%; behold the power of compounding alpha.

Write stuff

Being prolific is underrated. The more different things you try, the greater the chance of discovering something new. Understand, though, that trying lots of things will mean trying lots of things that don't work. You can't have a lot of good ideas without also having a lot of bad ones. —- Paul Graham (********** UPDATE 20230808 **********)

This “collegial approach and the scientific method” lends itself well to the writing culture found at Stahl’s Horizon Kinetics, which consistently publishes interesting papers detailing their thoughts on investing opportunities and current investments, either as quarterly commentary that is usually for the benefit of existing shareholders or as other miscellaneous musings that explain how Stahl and Bregman are thinking about particular opportunities or issues in the investing space. In a Value Investor Insight interview with Murray Stahl, he had this to say on HK’s writing culture:

One could imagine that as his firm’s assets under management grew into the billions – they currently stand at $8.1 billion – Murray Stahl would have given up the investment-research business he also started when he left Bankers Trust in 1994 to co-found what is now Horizon Kinetics LLC. After all, publishing research with titles such as Contrarian Research Report, The Special Situations Report, The Spin-Off Report and The Devil’s Advocate Report, as he puts it, “is kind of like committing to writing a term paper every week for the rest of your life.”

So why continue to do it? “We’ve found it to be integral to the investment process,” he says. “Writing things out for public consumption requires that you explain your investment ideas under the assumption that your interlocutor, in this case the reader, has zero knowledge of the investment you’re speaking about. Were we just working through something among ourselves, discussions would be far more likely to begin with a certain set of assumptions, which unfortunately, as much as we hate to admit it, are sometimes just wrong. The only effective mechanism we’ve found to force all of us, including myself, to challenge and re-evaluate assumptions is to require that we write it all up.”

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos similarly fostered a writing culture at his company for for very reasons. Firstly, he recognized that writing promotes clarity of thought, a vital goal for his team. Additionally, Bezos believed that writing facilitates deep thinking and critical analysis, leading to improved decision-making. By encouraging writing, Bezos aimed to nurture an innovative culture at Amazon, where new ideas could be generated and shared. To enforce this, Bezos even went so far as to ban PowerPoint presentations and required employees to compose narrative memos limited to six pages that were structured around introduction, goals, tenets, current state (of the business), lessons learned (from the current state), and strategy (going forward or for disruption / differentiation); you can see more about this framework, here. The most effective memos underwent multiple revisions, seeking feedback and fresh perspectives.

During meetings, Bezos and his team would silently read the memo for the initial 20 minutes, preparing for a more meaningful discussion. This writing-centric approach has profoundly influenced how Amazon creates, shares, and garners support for new ideas. This emphasis on narrative memos over presentations has shaped Amazon’s ideation and dissemination practices.6

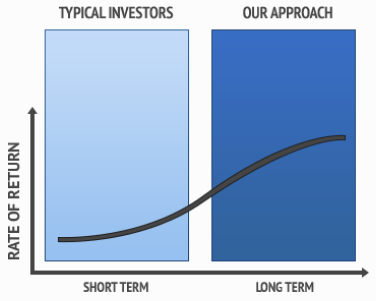

Long term thinking and the equity yield curve

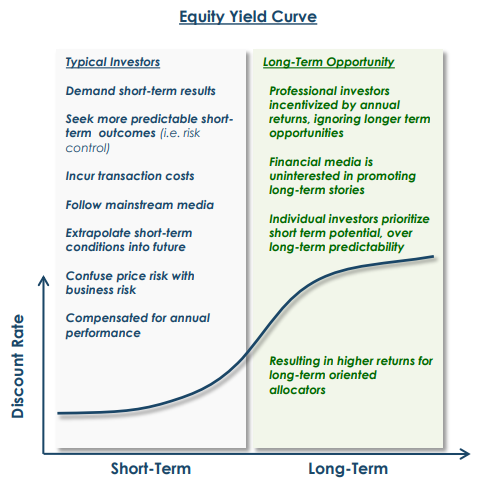

http://kineticsfunds.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Equity_Yield_Curve_Final.pdf

The name of the Stahl, Bregman, and Doyle asset management partnership “Horizon Kinetics” itself is based on the idea of them putting their energy (kinetics, if you will) towards the long term time horizon (as explained here by HK partner Peter Doyle). (You can see this still remains in HK’s mutual fund marketing materials). You can certainly see this philosophy at work when looking at the turnover rates for HK’s mutual funds’ holdings, which are around 3%/yr on average.

“If we wanted to, we could buy conventional equity securities that are marginable. We could probably buy somewhere between $90–$100 million worth and not have to liquidate $1 of an investment. There are no plans to do anything like that, but we could do it. I only mention that because we’re in a vastly different strategic position than we’ve ever been before. We don’t have to swing at any pitch if we don’t like it. Sooner or later, we’ll find something interesting to do with the cash we’re throwing off and, hopefully, it will be a cash generative business, and it’ll just generate more cash.”, https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2015_Q3_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

“Horizon Kinetics LLC (“Horizon Kinetics” or “Horizon”) began writing about the theory of the “equity yield curve” in the early 1990s and has since successfully applied it as a cornerstone of our investment philosophy. It validates the virtues–and elucidates one of the underlying enabling principles–of long-term investing. [...] The compensation structure of the investment management industry is broken down into artificial time horizons. The typical hedge fund manager’s bonus, or incentive fee, is based on year-end results. Thus, securities not perceived as having the ability to perform within that time period are typically avoided, even if their long-term potential may be extraordinarily attractive. In other words, money managers in general have an asymmetric aversion to underperformance versus outperformance, and economic incentives lead them to focus on short-term results. Hence, a future event that will have a decidedly positive impact on the price of a certain security, undisputable though it may be, has limited utility to the professional manager if that event is expected to take place beyond his or her artificial time horizon. Accordingly, the value of that event is heavily discounted by the market.”, http://kineticsfunds.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Equity_Yield_Curve_Final.pdf

“The further out the potential investment reward, the steeper the equity yield curve will be. Events occurring three to five years in the future offer little utility to the average portfolio manager. Over the short term, a company’s stock price is influenced by many factors and can fluctuate significantly relative to the long-term value of the company’s business operations, as measured by its book value and return on capital. We seek to identify these resulting long-term pricing anomalies to generate unique, above average returns. Acquiring investments at a high discount rate provides a reduced chance of losses. At a minimum, we expect to earn the underlying businesses’ return on capital over time.”, (Stahl, Bregman, & Doyle)

* I will note that while low portfolio turnover is often promoted as an important part of successful investing —in some phrase or another— by many successful investors, it is apparently not actually greatly correlated with investment returns according to a study of US domiciled funds (of course there are many ways to interpret this information and is something I will have to come back to in the future).

Further reading:

Identifying a few big trends and sticking with them

“So for example, I’d read Julia Childs’ autobiography and what I found is, no matter what they did – you could say in one sense their success was accidental and in another sense it really wasn’t – was they had an interest in it. What does it have to do with making money? Well she made a lot of money. Julia Child was the first person in the United States to popularize French cooking. [...] She was enormously popular in the 70s-80s.” —- Murray Stahl on reading about other successful people

“One way to characterize his almost singularly differing worldview is that he would find something interesting, and which he came to know well, and stayed with it. For the preponderance of the market, particularly the index and asset allocation-model investors, every quarter, or certainly every year, they gravitate from the set of investments that were popular that year to those that are popular in the next year. One reason this is not a very successful strategy is that it implies the manager has to know a great deal about a lot of investments, whereas John Templeton only had to know a great deal about a few investments, and he understood them very well. He simply left them alone and let compounding do the rest. ” —- Murray Stahl on investor John Tempelton

This appears to be the strategy Stahl is going for with FRMO’s inflation bets which themselves are largely confined to oil and cryptocurrency, both of which have had many FRMO and HK publications dedicated to describing the logic of these trends long before “inflation” —in a transitory or non-transitory context— ever came to the fore of mainstream news.

The value of cash (and the discipline to hold it)

“It takes character to sit with all that cash and to do nothing. I didn’t get to where I am by going after mediocre opportunities.”

—- Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie's Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger

I think that the typical investor’s journey goes roughly along the lines of: Speculation and Trading ==> Meme-stocks ==> Cigar-butts ==> Value ==> Growth ==> GARP; I believe that Buffett has commented on this pipeline once before, though I can’t find the reference right now.

UPDATE 20230401: Munger mentions this briefly in an interview with Todd Combs (GEICO’s CEO and Berkshire investment officer)…

Combs: So coming back to this transition that you helped [Warren Buffett and Berkshire] form from cigar butt to compounders, was that a sudden or a gradual awakening for you? Was there an epiphany of sorts?

Munger: Frankly, everybody who’s smart eventually makes that transition when they think about investments. Of course, if you can get into a great company. Stay in for a long time. That’s the easiest and biggest money you can possibly make. […] [The trouble] is that they sell so high priced that they make it hard for you to get […] that maybe it’s not such a good investment. […] But I think the people to tend to get the best results are these fanatics who just keep searching for the great businesses. And the best of them don’t expect to find 10 or 20 or 30. They find one or two. That’s the right way to do it —but that’s all you need are one or two. […] That isn’t what they teach in our educational institutions.

And while you may be able to find analogies to many elements of Stahl’s investment style in Chris Mayer’s “100-Baggers” (and thus Nick Sleep, Chuck Akre, et al) which I think is a really great compression of the characteristics of successful GARP investing components, one thing that would be a definite outlier vs Mayer is Stahl’s view on holding cash.

As a practical matter, I don’t usually have significant levels of cash (say 10% or more) unless I sell something, which doesn’t happen too often (or shouldn’t). Also, it usually doesn’t take me long to find something. —- Chris Mayer

Cash looks worse, though, if you look one year out, especially with inflation running circa 8%. And it looks terrible over ten years. If your horizon stretches ten years or more, then owning a good business is one of the safest places to be. —- Chris Mayer

While managing investments in both his asset management business HK and his public vehicle FRMO, Stahl has held large allocations of cash for extended periods of time.

Here’s what FRMO management had to say about their large cash position in 2014:

Cash and Equivalents. This segment comprises roughly 24.6% of total corporate assets. Ordinarily, since cash produces essentially no return, this would severely limit our possibilities for earning a robust return on shareholders’ equity. In fact, we were able to avoid this problem for two reasons.

First, as noted previously in this text, we were easily able to use the cash as collateral for our short sale activity. A successful short sale of one dollar of a path dependent ETF is over 200 times as productive as cash, even if interest rates were somewhat higher. Moreover, we only needed to use a very small proportion of our cash balances as collateral. In fact, the short sales themselves produce cash.

Second, the revenue share from Horizon Kinetics is structured to be a high return vehicle that generates cash with no reinvestment requirement. Most corporate earnings streams require the reinvestment of a significant quantity of the earnings generated. It is therefore obvious that our situation is unique. [For context, FRMO is currently mainly a holding company, rather having an operating business with associated opex, and holds many investments that act as royalty streams which require little maintenance capex and generate lots of FCF —I’ll go over this a bit more in the following sections]

It should also be obvious that our cash balances vastly exceed our normal operating requirements. We are therefore in a position to invest a substantial amount of capital should the opportunity arise. In fact, given that shareholders’ equity now exceeds $94 million, we could, in principle, borrow against that sum, as we are a debt free company. This is not to assert that we are about to engage in such an undertaking. The purpose is merely to observe that we could theoretically write a very substantial check if such an action were desirable.

Thus, cash is a quasi dormant asset that can be mobilized to increase return on equity. It is only quasi dormant as it does serve a collateral purpose, in part. This cash sum, when considered as only part of our liquidity in addition to our closed end bond fund assets and potential borrowing capacity, should give the reader a proper sense of our total available liquidity. Such a figure, even calculated most conservatively, comfortably exceeds 50% of corporate assets.

From a more recent 2018 HK commentary…

In classical portfolio theory cash was treated as a much more strategic asset than it is today. Today, many think of it as a wasting asset or a strictly temporary refuge during so-called ‘risk-off’ periods. […] The original idea, though, was to select an asset allocation mix that would suit your long-term risk tolerance level, measured by the price volatility of your portfolio. If you wanted less volatility, you could increase the cash level.

[…] In our case, we don’t mind interim stock price volatility; we’re more concerned with long term returns. But the opportunity set for attractively priced securities is quite narrow, and the systemic risks quite great. One shouldn’t feel compelled to take one’s cash and place it at risk just because you’ve allocated it as available to be invested. In this regard, there are two additional features to portfolio practice we might add.

One is time diversification, which is not much discussed; discussion almost exclusively centers on security diversification. But the long-term return you get is powerfully determined by when you start: at the top of a market, or 6 months later at the bottom? […] There’s value in a measured approach to capital commitment, and with time comes opportunity. [Reminds me of that Charlie Munger quote on how to get rich if you inherit a million dollars].

The other element of cash is that its value is far more dynamic and elastic than people give it credit for — in that its purchasing power rises dramatically when other assets decline. Here’s a quick Rorschach test, an inkblot picture of a serious global trade war. What do you see? If you’re fully, optimally invested, as is said, in the various global equity and emerging markets and investment grade and non-investment grade bond funds, it might look like a terrible storm. If you have a meaningful cash reserve, it might look a lot like a candy jar, for heaven knows what goodies might be inside. [While written during the time of the US-China trade disputes of 2018/19, this is also a rather salient comment today given the current goings on and knock-on effects stemming from the Russia-Ukraine situation]

********** UPDATE 20240206:

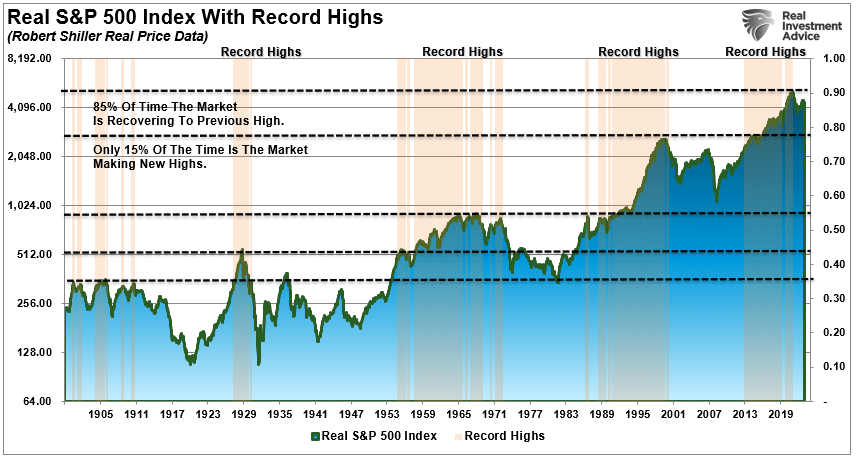

Bregman’s comments on ‘long-term returns being heavily influenced by when you start’ reminds me of this interesting commentary from Lance Roberts’ RIA site.

“Over time, stocks go up more often than they go down. In fact, stocks go up about 80% of the time. However, it is the 20% of the time they go down that is the problem. As shown below, over the entire market history, on a buy-and-hold basis, stocks only make new highs about 15% of the time. The rest of the time, they are making up for previous losses.”

**********

I’m not saying either style is better than the other —one thing you see a lot across the investing spectrum is that there are many different ways investors can succeed— and you can kinda see in this case that they’re not really coming from POVs that are very ideologically dissimilar (perhaps Stahl is just much pickier than Mayer), but rather I wanted to point out how Stahl’s POV on cash is interesting and uncommon to see in combination with his otherwise GARPish style. You could say that Stahl’s barbell strategy is a lot leaner in the middle and heavier on the ends.

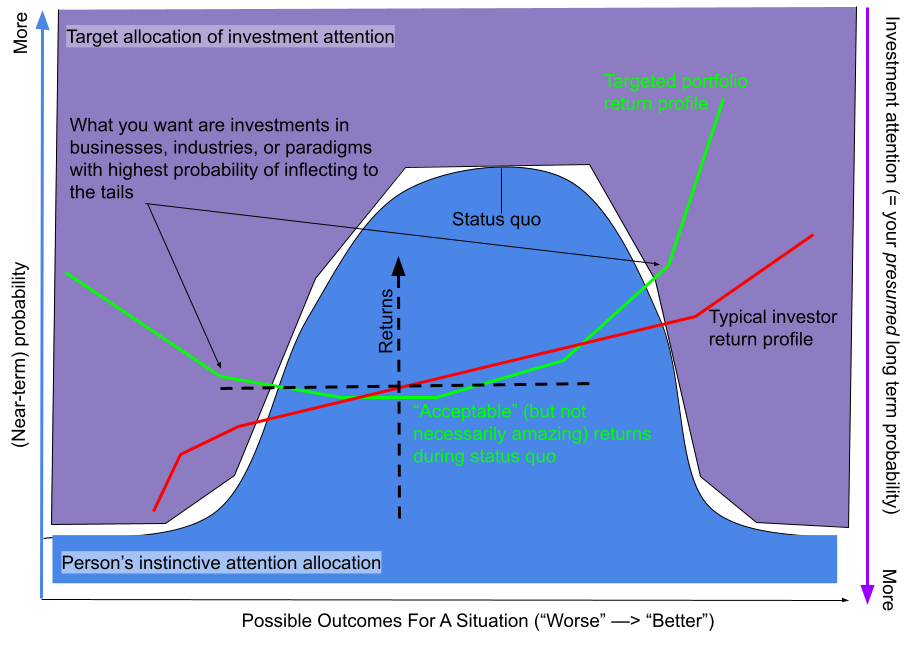

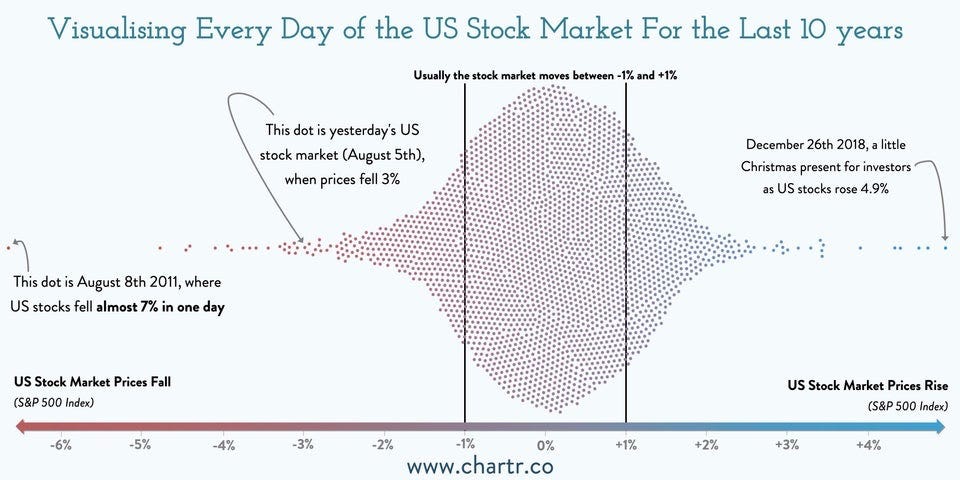

I will again reference this graphic from Howard Marks:

Further reading:

https://web.archive.org/web/20161024041708/http://www.horizonkinetics.com/sm_cash_as_liability.asp

https://web.archive.org/web/20200920101929/https://horizonkinetics.com/cash-as-a-liability2/

https://web.archive.org/web/20200920104431/https://horizonkinetics.com/cash-as-a-liability3/

https://web.archive.org/web/20200927031013/https://horizonkinetics.com/what-does-sam-zell-know/

Some interesting commonalities between Stahl and Franco-Nevada founder Pierre Lassonde

“If you have a choice between going to work for a wonderful business that is not capital intensive, and one that is capital intensive, I suggest that you look at the one that is not capital intensive.” —- Warren Buffett (1991)

Stahl has complimented, gold royalty company Franco-Nevada founder, Pierre Lassonde’s7 business model as being so brilliant it made him jealous that he hadn't thought of it himself, so it makes sense to see that he would incorporate similar themes in his investing style.

Interestingly, both Stahl and Lassonde ostensibly did not start their companies (Horizon Kinetics and Franco Nevada (FNV), respectively) with the primary focus of making a lot of money. Allegedly, Lassonde and his partner wanted to relax and ski and have some way to write it off on their taxes as a business expense, while Stahl just wanted to set his own schedule and goals and “hang out” with people he liked (presumably HK partners Steve Bregman and Peter Doyle, et al) while living a reasonably comfortable life (00:25:15).

Both invested heavily in royalty companies8 (which Lassonde believes is “The Most Powerful Business Model Ever Created”9 (00:19:55) and talks a bit more about royalty optionality here (00:28:00)). Stahl with his increasingly concentrated investment in TPL starting in the late 80s-early-90s (TPL was the subject of HK’s first research report in 1995, see here) where —from an Active Voice interview with Stahl that is now pay-walled— it is apparent that Stahl was initially focused on the return via the business’s mandated buybacks and dividends with the free optionality of oil price/discovery and land monetization aspects of TPL being a bonus.

When we first bought into this in 1995, we basically signed on for a 5% or so return from stock buybacks and the dividend, with pretty much infinite call options on what they could make happen with the land. —- Murray Stahl, “Value Investor Insight”, Nov 30 2018

Stahl continued to add to the position as TPL kept discovering more and more oil and extraction technologies improved to increase the amount recoverable; Lassonde of course founded gold royalty streamer FNV.

Here is Lassonde talking about royalty companies and optionality:

“They don’t understand what we have when we create a royalty. I’m not talking about a stream; I’m talking about a royalty — like the GoldStrike royalty or the Detour royalty. We get a free perpetual option on the discoveries made on the land by the operators, and we get a free perpetual option on the price of gold. Think about this – if someone hands you a free perpetual option on 6 million acres of land, and you don’t have to put up a penny, don’t you think that at some point, you’re going to get lucky?

That’s what it is. We have put together a land package by purchasing and creating royalties where we end up with a free perpetual option. It’s the optionality value of the land, the value of the operator spending money on our land, and the optionality to higher gold prices [ie. a lot of variable ways to win beyond the existing operating business (hence Stahl’s reference to “contingent business”)].And that is worth so much money. And yet, when the analysts calculate an NAV, none of them ever look at the optionality that we have in our portfolio. Frankly, it’s what’s worth the most. [...] When you buy a stream, on the other hand, you get price optionality.”, Pierre Lassonde https://www.mining.com/web/pierre-lassonde-franco-nevada-very-few-get-this-but-its-worth-so-much-money/

Royalty businesses basically have very high operating leverage, since they have such low costs in general —note that FNV just sits on land and today only has some 30-50 employees— and thus high CFFO margins that can be reinvested, while taking on very little solvency risk like a financially leveraged business would have (given the low overall cost structure).

For any royalty-like business, you just sit on the existing ongoing operations and wait for time and human innovation (of others) (+ the geological situation of your royalty holdings) to unlock optionality value in the future. All you have to do is make sure you pay the right price so you at least an be confident in getting paid back on the principal (which according to Lassonde is something like 5x (CFFO - maintenance capex), ie. a 5yr payback)10.

Royalty mineral rights and streaming rights are like owning the gold (or whatever other commodity or non-perishable asset the company focuses on) in a vault, in this case the vault is the crust of the earth (so the storage is basically free and perpetual). Here, that gold can “grow” magically as more deposits are discovered by the operators on the land and new technologies (R&D’ed by the operators) make existing deposits more profitable to extract from (either by increasing yields or reducing extraction costs). Operators pay you cash for permission / the right to extract that gold from the “vault” and you don’t have to lift a finger.

Further reading on Stahl and his thoughts on gold royalties:

https://latinmines.com/pierre-lassonde/

In this next section, we can see Stahl talking about a similar concept, but adding his own generalization to it…

The logic of investing in (non-perishable) optionality

In the 2020 shareholder meeting for Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett was asked about investing for inflation and he had this to say:

“And in terms of capital intensive businesses, they’re just not as good. If you can find an equally good business in terms of operations that doesn’t require capital. [inaudible 03:43:12] never required capital. [...] So you really want a business and everybody wants a business that doesn’t take any capital to speak of and keeps growing. It doesn’t take more capital as it grows. [...] And that’s why they’re worth a lot of money because they make a lot of money and they don’t require the money to any great extent in the business. We own some businesses like that, but it’s certainly not the railroad and it’s not the energy business. There are good businesses. We love them, but if they didn’t take any capital, they’d be unbelievable. That’s what we’ve learned from 50 or 60 years of operating businesses that if you can find a great business that doesn’t require capital, when it grows, you’ve really got something.”, Warren Buffet in response to the question of “...how do you think about the inflationary or even deflationary risks for all of the capital intensive businesses and could this to be an existential problem for businesses?” —- Warren Buffett at the 2020 BRK annual meeting

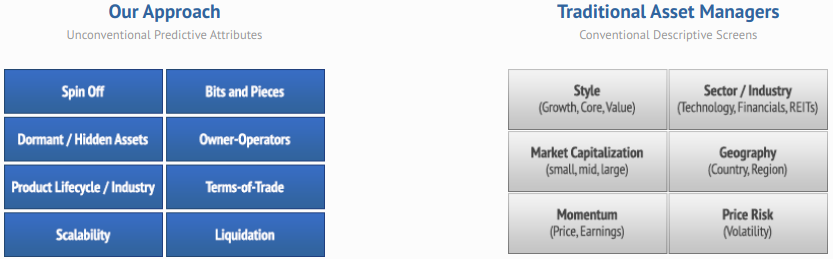

Looking at the HK website, there are several investment areas that the partners like to focus on:

“Our business analysis often emphasizes companies with unconventional attributes, including long product life-cycles, defensible competitive advantages, dormant assets, scalability, strong company leadership, favorable terms-of-trade, or companies that are experiencing structural change.” —- (Stahl, Bregman, & Doyle)

The largest allocation I see from Stahl are investing in businesses with embedded optionality11. Stahl phrases it as businesses with dormant assets or contingent earnings. This is something Lassonde has talked about regarding the royalty business and the idea of buying free optionality is something that Stahl has incorporated into his various investments over the years.

“From the FRMO standpoint, we ourselves diversify into a different asset class with significant positive optionality. We define optionality as the ability to earn substantial sums without investing substantial sums in relation to shareholders’ equity. [...] FRMO’s investment in the South LaSalle Partners LP (SLP) is essentially an investment in the Minneapolis Grain Exchange (MGEX). This asset is also performing well. In the first instance, higher volume contributes mightily to the economic success of exchanges since many of the costs are fixed. Rising revenue does not generally entail commensurate increases in costs. Consequently, the opportunity exists for large increases in profits. In accordance with our thinking, this is a form of optionality. [...] We can only wonder what might happen if the bear market in commodities were to end. Thus, the potential for higher volume is a form of optionality. [...] We are always considering other “high optionality” seedling businesses. The table above might change dramatically if even some optionality is realized. This could be the case even if we do not make any other “high optionality” seedling investments.” —- https://frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2015.pdf

From this example, we can see that Stahl pretty much is referring to low-cost scalability here similar to royalty businesses; trying to max out operating leverage with as little solvency risk as possible. This conception of “optionality” comes across a bit clearer in another FRMO shareholder meeting where he brings up the idea of “dormant assets” and the “equity yield curve” (more about that here and here) — fitting with HK’s philosophy of focusing on the LT time “horizon”:

“In our investment work, we happen to like owner/operators12, but it’s not really a requirement. We like dormant assets, which we define as those that are potentially productive, but that are dormant at the moment. Generally speaking, we have this idea we call the equity yield curve, which is the idea that an asset might be productive in a year or two. It’s a discount rate that the market applies to an asset that’s potentially productive rather than actually productive at the moment.

[...] We also pay a lot of attention to what we call optionality, and dormancy is just one example of that. It’s possible to get a lot more revenue without a lot more expenditure. So, we spend a lot of time thinking of that. OneChicago is an example of optionality, as are exchanges. If you find a small exchange that, in principle, can take a lot more business on its platform, you don’t need to increase the expenses very much. That’s an example of optionality. That’s why you’ll see that we have some exchange investments on the balance sheet like the Minneapolis Grain Exchange, OneChicago, and the Bermuda Stock Exchange.

[...] The question references The Money Masters by John Train, and the Warren Buffett quote about the ideal business being one that has a royalty on the growth of others. It is kind of like that, except we prefer not to say royalty; we prefer to say optionality. Why do we say optionality instead of royalty? Because it is business that is contingently there, as opposed to business which is actually there, and you own a piece of the business; therefore, you get a royalty on the growth of others. It’s contingently there. At the end of the day, it’s still growth. So, I guess maybe we’re splitting hairs and it’s talking about the same thing.” —- https://frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2016_Q1_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

TBH, I do think they are splitting hairs a little bit here. May need to look into this further to get more firmly on one side or another. It’s not quite the same as simply investing in industries during their down-cycle, but rather investing in businesses with existing (dormant) assets in place —or easily/cheaply capexed— that can easily scale for more revenue when the winds are in their favor (so more agnostic to the economic cycles of a business).

A working example of how Stahl thinks about this concept can be seen in construction of HK’s Inflation Beneficiaries ETF which is described in the fund’s overview slides and 2020 annual letter.

Accordingly, we believe that these companies can generate satisfactory shareholder returns under differing inflation and interest rate scenarios [read as: ‘not what our long thesis anticipated‘], yet have the potential to perform much better as inflation rises. In other words, the most effective strategy will be one that benefits from, but is not a binary bet on, inflation – these are not ‘heads you win, tails you lose’ businesses.

Bringing together various comments I’ve heard or read from Stahl on these kinds of businesses, a common profile of a company with valuable dormant assets is one that:

Operates a basic, cash flowing business that provides capital to fund asset purchases. Eg. the continued accumulation, improvement, or maintenance of such assets —in that order of priority.

Uses the operating cash flows to systematically buy and hold long-term assets that act as stores of value —which in turn can allow the company shares laying claim to the assets to act as stores of value13.

Chooses assets that are durable or non-perishable, so they have an indefinite or very long shelf life. This makes the call option on the assets nearly perpetual.

Focuses on assets that are highly durable, portable, fungible, verifiable, divisible, scarce, and typically have an established history of being valued by society. That is…

Acquires either productive and non-productive assets that have global market bids and (usually) historically increasing demand curves. It may sometimes simply be the case that the asset is extremely scarce and has some reasonable value proposition which could make it valuable in the future.

The assets being accumulated may not be correlated to the core business, providing an element of diversification.

Chooses assets with deep, liquid markets that facilitate purchase and future sale —contributing to the store-of-value qualities of the asset and thus the company stock itself.

The assets increase the liquidation/replacement value of the company —and this may not always show up in GAAP accounting, for example if the asset is land and it is held on the books at cost for very long periods of time.

Operates with a long time horizon, allowing the value of assets to appreciate.

Examples of such dormant asset stores of value could include precious metals (eg. Franco Nevada), cryptocurrencies, industrial commodities (eg. mineral rights companies), real estate / land rights (eg. Howard Hughes Holdings), physical or technical infrastructure and user networks (eg. regulated and capex-intensive infrastructure project held by Brookfield Corporation or securities exchanges like OTC Markets)14, films/media rights, art, diamonds (eg. Diamon Standard), etc. The core principle often seems to be using a basic cashflowing business to systematically acquire non-perishable, store-of-value assets when they are cheap or fair-value and hoard or distribute cash when such assets are expensive.

“[B]uy something with little available supply today that might be in great demand and revalued upward on some tomorrow. Informed patience is required for this […] As powerful as compounding is, it nevertheless takes quite a bit of time to manifest itself sufficiently to stand out above the short-term growth trajectories and valuation fluctuations of standard businesses. So, to realize the benefits of compounding requires informed patience; it can’t be disturbed or ‘optimized’ by trading in and out of it.” —- Steve Bregman, https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Q4-2023-Commentary_FINAL.pdf (UPDATE 20240208)

********** UPDATE 20240808: I was reading HK’s latest quarterly commentary which included a discussion re. China and the threat that would be posed to many popular US tech businesses if China were to set their sights on taking their knowledge from their years of acting as the world’s factory for many of these popular brands and shift to direct competition and manufacture on their own account. This would theoretically be a major —and in HK’s estimation, not very thin— left-tail risk for these tech giants whose econ. moats are largely based on branding (low negotiating power of buyers / lack of *real* substitutes in cases like Apple or Tesla) and —perhaps to a lesser extend— econs. of scale (for the likes of Amazon). This is a theme/idea I’ve seen them express at various times as far back as 2016ish.

From a Hamilton 7 Power’s POV (https://7powers.com/), these companies may have have: scale economies, network effects, branding, and process power —but perhaps have low (theoretical) switching costs.

I personally don’t think China has the cultural or legal “infrastructure” in place to compete with these Anglosphere businesses in a meaningful way (and these impediment seems like the rather durable sort). Have you ever seen what the Huawei phone UI/UX is like (or the telling insecure cope of it’s users)? Do you think that foreign businesses will have an easier or 100x worse time trying enforce their legal rights on a Chinese co. in Chinese courts vs in the Common Law Anglosphere? (India on the other hand may be another matter).

However, rightly or wrongly, from this theoretically-possible, left-tail POV, it’s a bit easier to see why (in conjunction with high operating leverage and low maintenance capex) HK has always tended to have a focus on businesses, with stronger *scarcity* dynamics, eg. those enforced by digital code (BTC); physics / physical limitation/scarcity (TPL); regulations (asset-light defense contractors like SAIC/CACI or licensed securities exchanges); or, to a lesser extent, those enforced by extreme tangible replacement costs vs incumbents or potential entrants (Brookfield Corp. or Howard Hughes Holdings)).

From a Hamilton 7 Power’s POV, these companies may or may not have similar characteristics to those of the favorite tech companies described earlier, but they also have a strong element of ‘cornered resource’ dynamics that cancel out any vulnerability from low switching costs. I recall that in Michael Mauboussin’s “Measuring the Moat”, he points to elements of the the Porter Five Forces of barriers to incumbent rivalry and barriers to new entrants as the most valuable types of forces for a business. **********

While the core business provides stability, the dormant assets offer asymmetric upside as underappreciated options on various macro scenarios playing out. Even if the odds of each scenario are limited, the payoff profile is nonlinear.

Stahl’s investment in Winland Holdings is an interesting example of this kind of strategy. They’ve taken the high-ROIC legacy business’s cashflows and (rightly or wrongly, depending on who you ask) used them to fund the mining of accumulation of Bitcoin on the companies balance sheet. I’ve written a bit about it here: https://lemoncakesinvesting.substack.com/i/135459053/winland-holdings-welx-data-center-monitoring-crypto-mining-and-crypto-bankruptcy-claims

Further reading: https://web.archive.org/web/20170201181502/http://horizonkinetics.com/docs/Dormant_Assets_December.pdf

.

This brings us to…

Investment convexity

********** UPDATE 20230205: I’ve read a good amount of other HK publications at this point and I think this segment isn’t true; I was just reading to much into things with other subjects in mind at the time. Though I was able to find this old HK essay on “Tail risk as an asset class” that I think is highly related. **********

********** UPDATE 20230801: Reading the recent 2Q2023 HK Commentary, I’ve since un-changed my mind on this topic. Though I will note that the “convexity” that Stahl appears to be trying to bake into investments is very specific to his ideas of the left-tail and more-probable-than-not outcomes for inflation and a bubble in the passive investment complex. **********

“And we need to be cognizant that they might not work—particularly cryptocurrency, but more about that in a moment—and size them so that if they fail, that wouldn’t be a fatal outcome for the company. As a matter of fact, with cryptocurrencies you wouldn’t notice a major change on our balance sheet. We would not be happy if it didn’t work, but it wouldn’t be a calamity, and we’d live to fight another day. That’s the whole idea. One of the themes in the shareholder letter is that when you explore the various elements of cryptocurrency, no one can know if they will work or not.” —- https://frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2019_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

“Our investment posture is designed to prepare for a problematic situation. However, even if this view proves to be incorrect, FRMO now has the financial resources to continue to develop in new ways.” —- Murray Stahl (2020 letter re. Inflation, indexation, and the US national debt)

Reading FRMO’s 2020 shareholder letter, it seems like Stahl wants to build in left tail convexity re. inflation and indexation trends, doing this via inflation beneficiaries that can still produce OK results if the world stays at the current paradigm (juiced up with a few “structural constraint” right tail call option bets that are agnostic of the general economy (eg. his investment in Diamond Standard)). If I had to diagram it, I’d say his attention is like this...

I may actually be giving a little too much credit to Stahl here on one of the left or right tails depending on how you define “worse“ and “better“ (may just have this interesting article still on my brain), but you get the general idea.

********** UPDATE 20230801:

In the recent 2Q2023 HK Commentary, HK co-founder Steve Bregman talks about the greatest investment risk of inflation as “that it is usually very costly to maintain a hedge against a contingency whose arrival date is uncertain, or which has arrived but will be persistent—which is to say a long-term hedge” and that “[i]t’s more important that they remain profitable during the long periods before that contingency manifests. Which is to say that the hedge actually earns a return during the interim.”

That is, serious commodity-based inflation —however likely S&B my see it— is still a nominally left-tail probability and not the norm that has been experienced for the last 40 years; it’s possible that it takes several years more for this issue to become fully manifested. Until that time, simply buying inflation- or commodity-linked investments would leave you greatly under-performing or otherwise taking on significant negative ‘roll-yield’ (even in an unofficial sense in the case of, say, a mining company that might have to tolerate greatly depressed or negative profits (or EPS in the case of having to raise equity in order to continue operations in a less favorable environment)) in the intervening period —assuming that this left-tail case ever comes at all.

In this light, HK’s investments in mineral royalty, security exchanges, and other asset-light businesses makes more sense as they’re fixed costs (that must be tolerated in every quarter along the road to the inflation that S&B see coming) are near zero, while they would still benefit greatly from a rise in commodity prices in any inflationary environment without requiring an investor to essentially ‘time the market’ by correctly predicting the “when” of deciding to take on a shorter-term investment as a hedge.

“The human mind plans the way, but the Lord directs the steps.” —- Proverbs 16:9

I’ve also talked a little bit more about these types of investments by Stahl in another post here:

**********

Like weeds in a garden: “Yes, and…” the power series of coffee cans and art dealers

“New asset classes are a learning experience for everyone. If expanded in a gradual, deliberate manner, every employee in all of Horizon Kinetics can have the opportunity to develop new knowledge and skills in an environment free from the pressure of substantial loss of capital. The existing businesses continue much as before. Thus, in the event of an individual project failure, employees are at liberty to return to their former responsibilities, or perhaps transfer to another related more successful project. Equally important, since the risk in any one project is constrained, the luxury exists to give the projects sufficient time to solve the inevitable difficulties that arise in any new venture.”, Murray Stahl (2019 shareholder letter)

“We’re investing in assets that are, let’s say, off the beaten track. The average person doesn’t do things like this, and we’re not investing tremendous sums of money. If bitcoin were to be a failure relative to our cost, especially net of taxes, it wouldn’t be a huge financial tragedy. To manage risk you have to start [by?] sizing things small. If you size it big and something bad happens, well, then you’re impeding your future.”, https://www.frmocorp.com/_content/letters/2020_Q2_FRMO_Transcript.pdf

“As a gardener, we plant seeds, provide the right conditions, and give enough food, water, and light. We observe the seeds and adjust our care if needed. And we let them grow. This is how we can parent our children, too. This is the Montessori way. We are planting the seeds that are our toddlers, providing the right conditions for them, adjusting when needed, and watching them grow. The direction their lives will take will be of their own making.”, Simone Davies (The Montessori Toddler)

“[Nature] has a passion for quantity as prerequisite to the selection of quality; she likes large litters, and relishes the struggle that picks the surviving few;”, Will Durant (Lessons of History)

“Strategies grow initially like weeds in a garden; they are not cultivated like tomatoes in a hothouse. In other words, the process of creating strategies can be over-managed. Sometimes it is more important to let ideas emerge than to force a premature consistency on the organization. Allow those strategies to form, as patterns, not having to be formulated, as plans. The hothouse, if needed, can come later.”, Henry Mintzberg15

The painting “Starry Night” (pictured above) was created in 1889 while Van Gogh was living in an asylum in Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in France. Van Gogh did not think highly of the painting and did not initially send it to his brother Theo, an art dealer in Paris, because he didn’t think it would sell. In fact, Van Gogh did not sell “Starry Night” during his entire lifetime. After Van Gogh's death in 1890, the painting was sold by his brother’s wife (Theo died shortly after Van Gogh) to poet Julien Leclercq. Now considered one of the most iconic and valuable works of art in the world, it has since passed through several private collections and is now part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. 16

Just as Van Gogh and his brother couldn’t predict the ultimate value of his own art collection at the time, investors often face similar uncertainty when constructing their portfolios. Stahl’s solution to this problem is similar to that of successful art dealers throughout history; to create portfolios with minimal turnover to allow the portfolio to converge on the best-performing assets over time. Stahl also adds select assets that can act as perpetual call options that are sized to create low overall value-at-risk to the portfolio, while retaining the ability grow into significant holdings in their success modes that can then contribute as one of the portfolio’s core holdings.

.

I notice that the two main styles I see expressed in FRMO’s holdings are:

1) concentrations in durable Coffee-Can, 100-Bagger type holdings (eg. TPL) and

2) smaller perpetual call-option bets that Stahl believes have the potential to become significant holdings over time (eg. BTC in 2014 and the Miami Options Exchange (MIAX) today). Horizon’s “dormant asset” terminology may be a better descriptor here, since the ‘call-options’ that Stahl is interested in are ones that don’t have an expiry date. These have often been funded by the dividends from the type-1, core, Coffee Can holdings of the portfolio —a way for large positions to fund their potential replacements in the fullness of time.

He tests something out as a small idea, expands on it and scales if it seems to be working, and lets it compound over the long-run —essentially yes-and’ing his way into a coffee can of concentrated holdings. This idea of power series convergence combined with patience and rational iconoclasm is confirmed in a 2008 HK commentary where Stahl says…

At inception, standard position size for me is usually 2%. I don’t change it radically over time, because I’m a big believer in the mathematics of what’s called self-ordered criticality. Ultimately, if you leave the portfolio alone long enough, whatever your best position is will eventually become your largest position. In other words, let the portfolio do the work. […] Given your view of the enterprise, if you thought it reasonable to establish a 2% position, and the company lost half its value, and all else remained constant, if you altered the position to make it a 2% position again then you’re effectively making it a 3% position. That should be done if it is concluded that the risk/reward at the lower level is far superior to all the other companies that are in the portfolio.

Let’s look at FRMO’s approach to entering the crypto space. Rather than building up a robust circle of competence in the field before diving on normally-size investments in the space, FRMO set up a bunch of smaller venture operations as a risk reduction measure to see which seedlings of highly promising ideas could grow into flowers and “letting the winners run” to build up the knowledge base gradually over time in these various toy projects that were given room to grow into larger operating businesses17.

You can also hear this from Stahl himself in this podcast snippet where he talks about how FRMO got into Bitcoin and cryptocurrency mining. I believe in other interviews Stahl states that their initial BTC investment in 2015 was somewhere around 0.5-1% of a portfolio18 and you can see his logic for this —and by analogy many of Stahl’s other small-cost-basis-high-upside-optionality bets19— in the HK publication “The Thesis for a Defensive, De Minimis Investment in Bitcoin” (the article here is even better for several more concrete examples20).

“For Texas Pacific Land Corp. (TPL), an older-vintage account opened more than two decades ago would have made itsfirst purchase in 2003 and bought about a 5% position. In the almost 21 years since, the price rose 182x, which annualized is nearly 30%. […] [W]e began buying Grayscale Bitcoin Trust in early 2017, at about a 0.5% weight. In the seven years since, Bitcoin has appreciated against the dollar by 43x, and that exchange rate differential, annualized, is 70%. In such accounts, the GBTC position weight is now more than 10%.” ~~~ HK co-founder Steve Bregman, https://horizonkinetics.com/app/uploads/Horizon-Kinetics-Q1-2024-Commentary.pdf 21

I think it's useful to note —and this is something S&B likely have in mind when making further crypto investments at FRMO— that crypto and GBTC initially started as tiny at-or-below-1% positions at FRMO and the HK funds in 2014 when 1BTC was ~$300. It was an investment that required only a small amount of value-at-risk, while (convincingly enough to Stahl after reading the Bitcoin whitepaper and putting it together with his ideas from Hayek’s “Denationalization of Money”) having the chance of 100x'ing —and it did more than that. That is, the thing to consider here is the upside of the small crypto investments in success mode and a humble view of position sizing that recognizes that crypto could go 100% bust if Stahl missed some critical POV or new unanticipated event in evaluating this brand new / emerging global asset class. Looking at the situation from a binary Kelly Ratio with 100-1000x eventual payout, but a, say 90-95% chance of total loss, is one way to understand how Stahl is likely thinking about incremental investments when it comes to crypto and his other small “call option” bets today.

********** UPDATE 20240208: More on this specific idea re. HK’s initial Bitcoin investment is directly addressed in the FY2023Q4 HK commentary here, see “A Significant Portfolio Development, in Three Parts: Part One, Narrowly”. One should consider the idea of Kelly Ratios (https://www.oldschoolvalue.com/investing-strategy/kelly-criterion-investing-portfolio-sizing/; https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2018/06/14/the-kelly-criterion-you-dont-know-the-half-of-it/; https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/TNWnK9g2EeRnQA8Dg/never-go-full-kelly). **********

********** UPDATE 20240109: Think of it this way, the average daily movement of the S&P 500 is about +/- 1%.22

If one’s portfolio dropped 1% in a single day, would you bat an eye? Put that 1pps in a highly volatile or operationally-leveraged investment that could go to zero due time (making up only a 0.20% total annual performance hit if the business takes, say, 5 years to fizzle out) or could 5x-10x-100x your money in success mode; you could end up with a downward movement in a year that you wouldn’t normally think twice about or a key investment over a longer horizon that could become a proper sizable position in your portfolio or completely reconfigure it. **********

This learning/growing by doing approach parallels nicely with the methods for optimal learning espoused in Scott Young’s Ultralearning (a really good book on learning that I wish I had found at the very start of getting my engineering degree rather than near the very end), specifically regarding directness and experimentation. Note that the TPL and BTC investments that now make up around 40% and 25% of FRMO’s TBV, respectively. Both started as much much smaller positions that were accumulated and/or allowed to grow in exposure as they succeeded over time23.

********** UPDATE 20230801:

This process that Stahl and Bregman used to build out their Bitcoin operations once he had read the Bitcoin whitepaper and concluded that Bitcoin would be extremely valuable —in success mode— reminds me a lot of, Y-Combinator founder, Paul Graham’s essay on “How To Do Great Work”:

Doing great work is a depth-first search whose root node is the desire to. So "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again" isn't quite right. It should be: If at first you don't succeed, either try again, or backtrack and then try again.

"Never give up" is also not quite right. Obviously there are times when it's the right choice to eject. A more precise version would be: Never let setbacks panic you into backtracking more than you need to. Corollary: Never abandon the root node.

Stahl mentions in the Q3FY2023 earnings call that they had to learn and go slowly into the Bitcoin space as there were no text book at the time written about the business and economics of the crypto industry. If there were, it would also likely have had to of been an already mature industry and FRMO might thus not have even been interested in pursuing any big investment plans in that area.

“If you don’t mind being wrong on the way to being right, you will learn a lot.” ~~~ Ray Dalio, “Hedge Fund Market Wizards”

**********

********** UPDATE 20240523: On the subject of the DFS algorithm, I found this Pivotal musing on Marc Andreessen’s X/Twitter bio to be very relevant here:

“Part one of Andreessen’s aphorism addresses this: strong opinions. If you’re going to do something, do it at full throttle. Night is falling; get to the village as quickly as you can. But if you find that the road you’re on dwindles into nothingness, don’t be stubborn about it; turn around! This is the second part of the aphorism: weakly held. The beauty of this combination is that it maximizes rate of learning.”

**********

In any case, this start-small-and-let-the-winners-run process can also be seen as recently as FRMO’s 1Q2022 earnings call (00:42:07) where I asked a question about the investments in the Polestar and Multi-Strategy Funds (which makes up the majority of FRMO’s LP investments). The CC transcript is a little messy, so I’m going to do a bit of editorializing here based on the CC recording:

“[Little] by little, we used the cash flow [to the] funds to establish [a position in] Mesabi Trust. Ultimately, even though nowhere near the size of TPL. Ultimately, the position becomes sufficiently big enough so dividend flow from Mesabi can pay for more Mesabi. So it's a self-replicating position. Meaning it's growing organically and that's the goal. To find maybe 9, maybe 10 if we can [find] positions like that – I'll describe them more in detail in a second where our criteria are – [where they’re self-replicating]. Remember, we're not allowing for cash flow. If we get it that’s great, [but we may not] get it. So ultimately [it] will grow and as they grow, there's more dividend flow. Ultimately it will grow bigger than our requirements to buy more shares [and] we'll find something else to buy.”

So here Stahl is collecting a basket of —typically, cash-flowing, royalty business— investments and DRIP’ing dividends back into these positions as a way to dollar cost average (DCA) in proportion to their ability to generate/distribute their cash flows.24

“I scale out, and I also scale in. The idea is don’t try to be 100 percent right.” —- Joe Vidich in “Hedge Fund Market Wizards”, Jack D. Schwager (also expressed by Roaring Kitty of 2020 GameStop fame)

“In the case of hard assets, because of the optionality and the fact that you get the cash flow as a shareholder, you should always be buying them —unless the asset trades at some excessively elevated valuation. We’re buying a little bit every single day because we’re not going to pick the high point and low point. There are just too many variables involved. When you trade securities and you think that you know what the high point and low point is, bear in mind that there are 253 trading days in the year and only one high price for the year and only one low price for the year. Who knows what day that’s going to be reached? You’ve got a 1 out of 253 shot of being right and I don’t like those odds. Therefore, I basically buy every day. On the days when the price is really low, the cash that we spend has a lot more purchasing power. Over time—say it’s a form of dollar averaging—you get the harmonic mean price and it’s usually a good deal.” —- Murray Stahl

This can also be seen in a discussion “On Concentrated Positions, ‘Locking in Profits’ and ‘Trimming’” in the HK commentary here which talks about simply buying a basket of select stocks and simply letting the losers lose and winners run to dominate the weightings of the portfolio over time into large concentrations of a few winners (as well as why this is structurally difficult for institutional investors and psychologically difficult for humans in general):